[From the Tax Justice Research Bulletin 1(4)]

The 4 Rs (or 5) of tax provide a simple basis for thinking about what effective taxation can deliver: not only revenues and redistribution, but also re-pricing of social goods and bads, rebalancing of an economy between sectors, and perhaps most importantly, supporting accountable political representation (in which the evidence indicates a critical role for direct taxation).

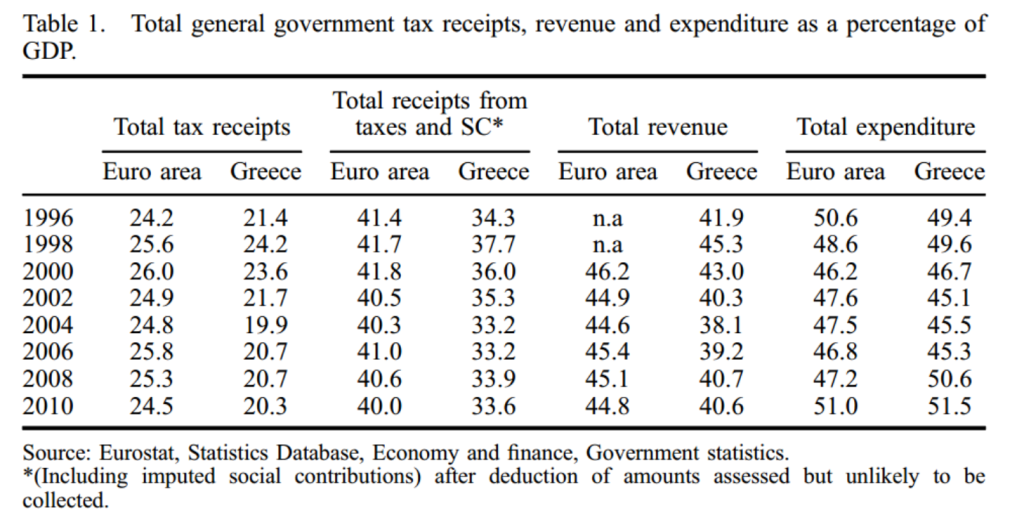

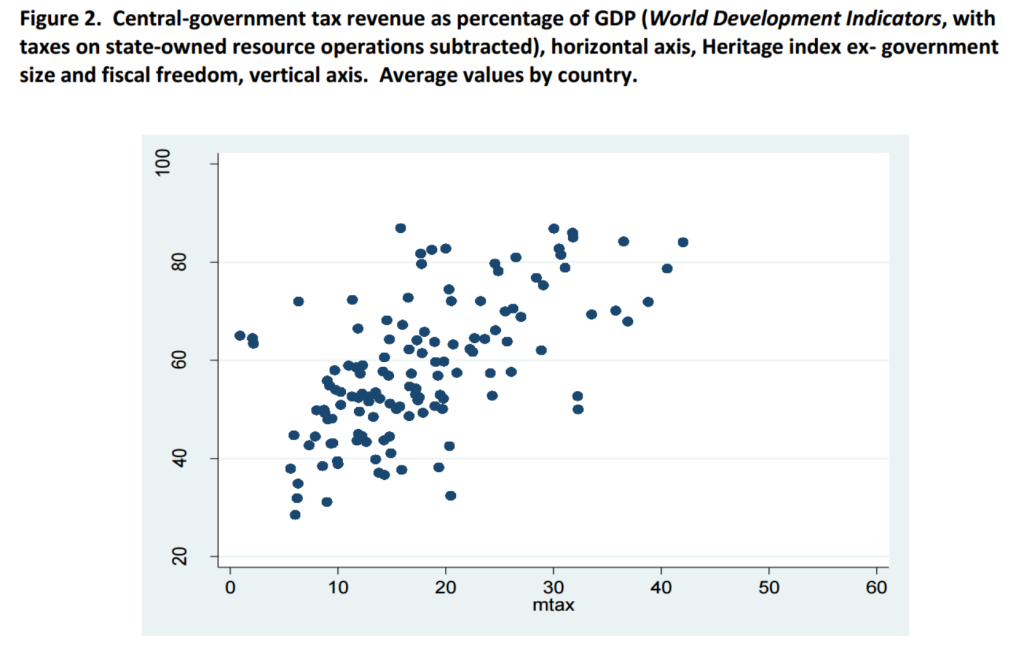

While popular analyses of Greece’s fiscal issues have tended to start and end with fiscal profligacy, a new (ungated) article by Yiorgos Ioannidis on ‘The political economy of the distributional character of the Greek taxation system (1995-2008)’ reveals that the problem is not high spending but weak revenue-raising; and that the underlying failure is one of representation as much as of revenues.

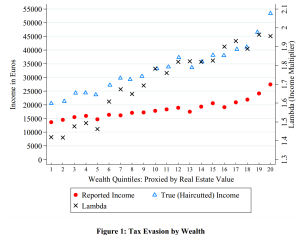

The starting point for Ioannidis is the disconnect from the mid-1990s between buoyant economic performance and the failure to close the gap in tax performance with the rest of the Eurozone – seen clearly in table 1. The specific underlying failure, as Ioannidis reveals, relates to direct taxation.

Despite the propitious circumstances of strong growth and a natural widening of the formal wage tax base, policymakers allowed overall tax receipts as share of GDP to fall – and in particular direct taxes fell from around 10% to 8% of GDP, with the majority coming from corporate tax cuts. Revenue reliance on indirect taxes, above all VAT, remained unchallenged – so that Greece’s tax structure continued to resemble ‘a developing rather than a developed country.’

Ioannidis explores much of the detail on policy mistakes, including the decision to use growing formal employment to fund corporate tax cuts, and in respect of property taxation. Most striking is the analysis of decisions around income taxation that actively undermined compliance, along with vertical and horizontal equity, and resulted in a highly regressive structure. If tragedy is the right word, it is because it could have been foretold to the protagonist policymakers beforehand that these decisions would squander both the economic and political development opportunities that presented themselves in the 90s.

The challenge for the new government is that rebuilding faith in public institutions, their fairness and representativeness, is necessarily a slow process. But while the need to raise greater revenues risks greater hardship on the way, it may ultimately support the virtuous cycle of better taxation and more accountable political representation.

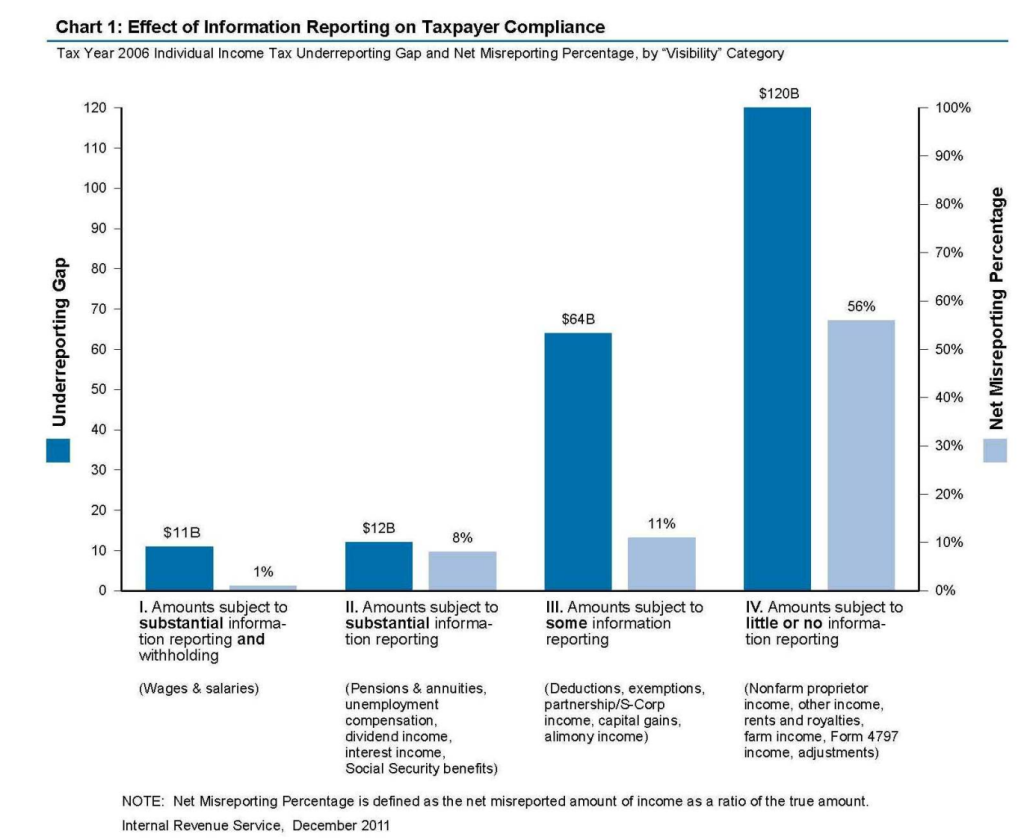

One role in this for Eurozone partners and other jurisdictions is to ensure the automatic provision of tax information that is necessary to curtail offshore tax evasion.

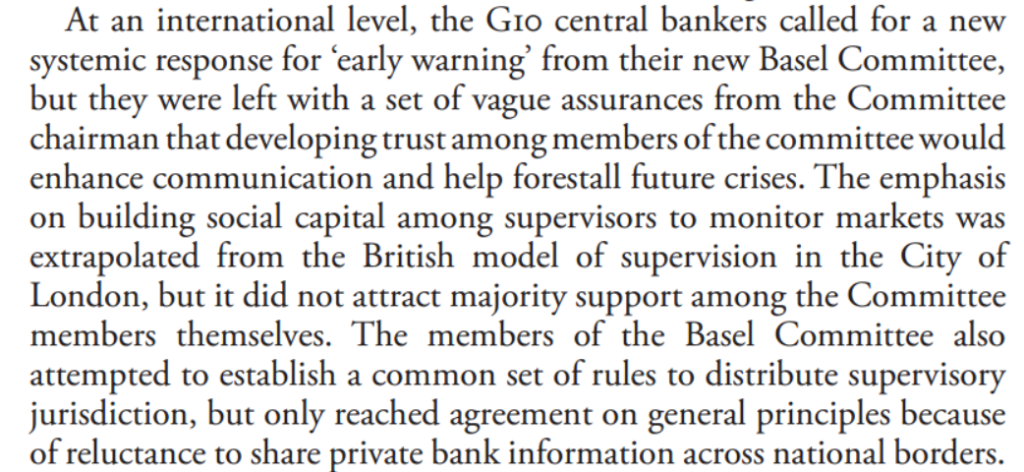

And in 1975, the creation of the Basel Committee. An important consideration was the gap between home and host country regulators, as it had been for the Committee’s predecessor the Groupe de Contact – and remained unsolved. The demand for an early warning system went unmet, in the face of different regulatory approaches and a common resistance to cross-border sharing of banks’ information.

And in 1975, the creation of the Basel Committee. An important consideration was the gap between home and host country regulators, as it had been for the Committee’s predecessor the Groupe de Contact – and remained unsolved. The demand for an early warning system went unmet, in the face of different regulatory approaches and a common resistance to cross-border sharing of banks’ information. A new paper

A new paper