If you had to pick a single measure for the tax performance of a country, or a government, what would it be? That question now confronts the folks working on the post-2015 successor to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as they seek an indicator for the global framework.

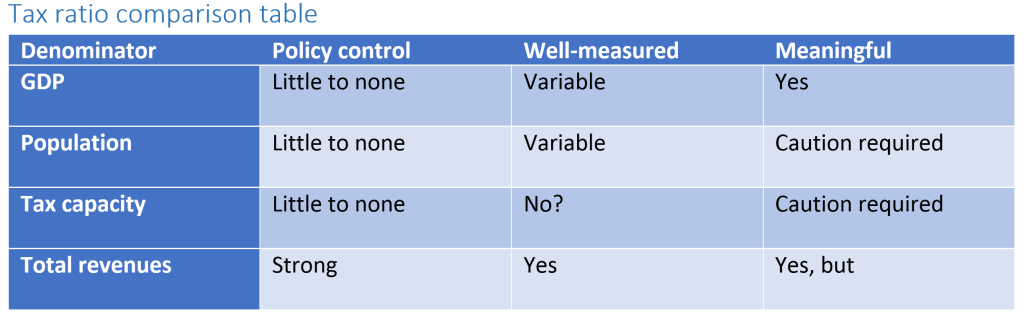

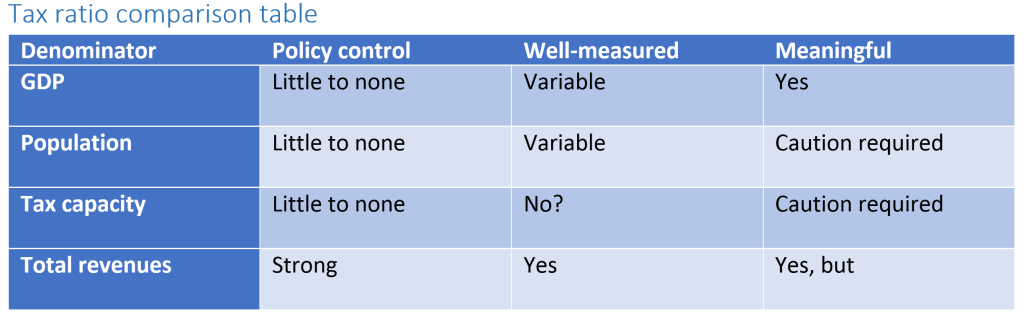

In this post I look at a few contenders, and their strengths and weaknesses. Quick thoughts on the main contenders are below; but if you’re short on time, the table has a summary.

And if you’re really short on time, the answer: for all its issues, the tax/GDP ratio is probably worth sticking with; while the tax/total revenues ratio is an important complement.

Assessing tax system performance

One of many areas in which the framework is likely to improve upon the MDGs is the attention to tax. This includes a specific target on illicit financial flows, encompassing individual and corporate tax abuses inter alia. On these, I made three specific proposals for the Copenhagen Consensus.

But the question that’s come up a few times this week is on the broader point of measuring tax system performance. How, in the period 2015-2030 (say), can we track the success or otherwise of tax systems? If you’re wanting to look into other countries systems, take a look here for information on Malta’s taxation system, as systems can change dramatically country to country.

The five Rs of tax

Ten years ago I proposed the 4Rs of taxation, as a simple way to think of what a tax system can or should deliver. Richard Murphy has since added a fifth.

- Revenue

- Redistribution

- Re-pricing

- Re-balancing

- Representation

To date, the focus has been almost entirely on revenue (‘domestic resource mobilisation’, in UN-speak). This makes sense, with one exception that I’ll come to.

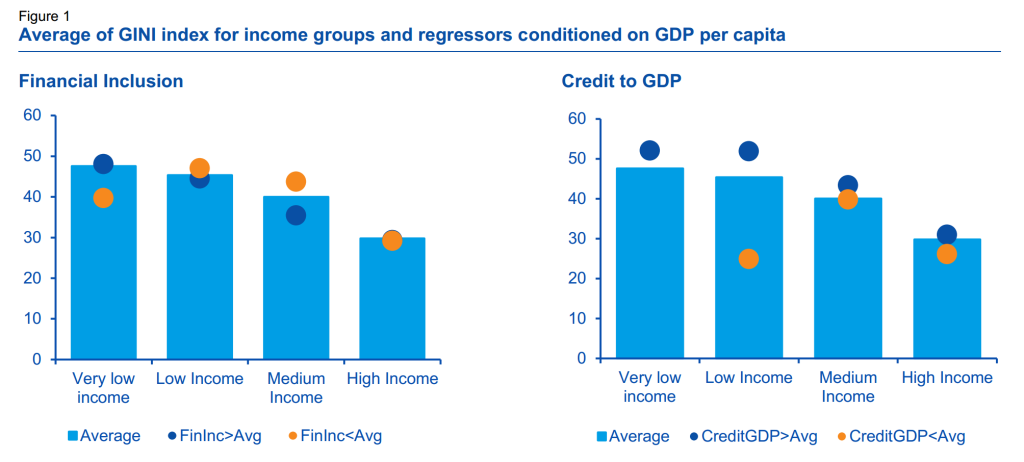

Redistribution will be treated elsewhere. To my excitement, the current draft includes 10.1: ‘Measure income inequality using the Palma ratio, pre- and post-social transfers/tax…’.

Re-pricing (use of the tax system to make e.g. tobacco or carbon emissions more expensive) is less central, and the climate aspect also features elsewhere in the framework.

Re-balancing the economy (e.g. addressing tax differentials to reduce the size of a too-big-to-be-efficient financial sector), Richard’s important addition, is also an option in a good tax system more than a definition thereof.

Representation, however, is a vital outcome of a good tax system. It is the aggravation of paying tax, and above all direct taxes (on income, capital gains and profits), that build the citizen-state relationship as people are motivated to hold government to account for their spending decisions. The alternative dynamic is too often seen in resource-rich states where tax plays only a small role in overall spending, and may also result from situations of sustained, intense aid flows.

Various findings, most recently and powerfully a new analysis with the ICTD Government Revenue Dataset, confirm that the share of taxation in total government revenue is an important determinant of the emergence of effective democratic representation.

So we should consider representation as the other core feature of tax, alongside revenues, when we look for broad measures of progress.

Criteria for comparison of tax measures

Since comparing cash tax receipts across economies of different sizes is largely meaningless, we need to take ratios. The question then becomes:

What ratio of tax receipts should we use for inter-temporal and/or cross-country comparisons of tax performance?

I propose three criteria. Ideally we would have a ratio where the denominator is in the control of policymakers; where the denominator (as well as the numerator) is well measured; and where the ratio is demonstrably meaningful as a measure of performance of the tax system.

Tax/GDP ratio

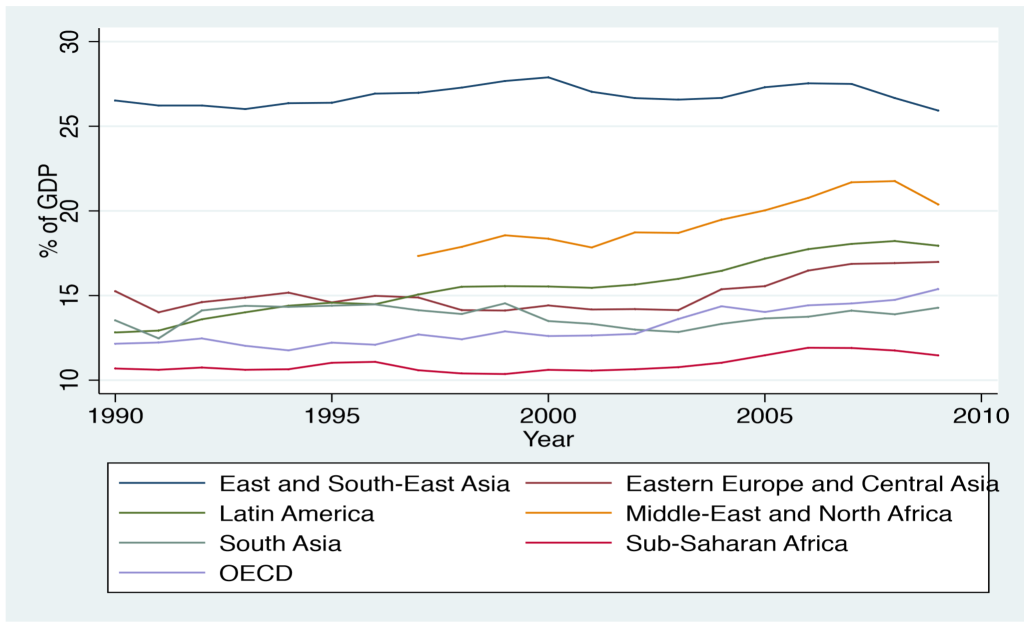

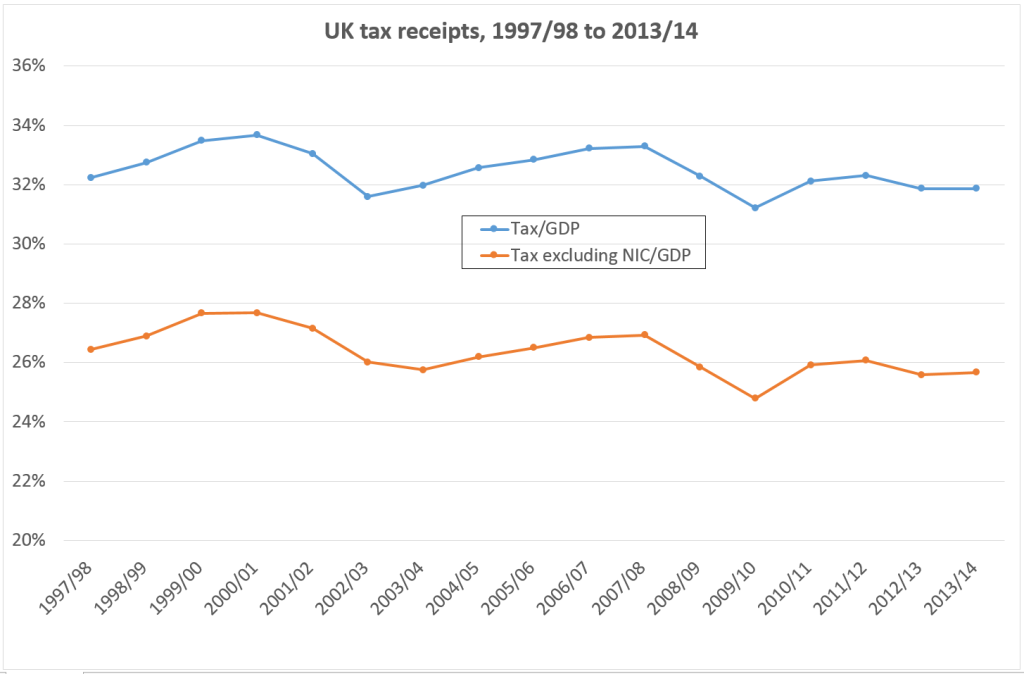

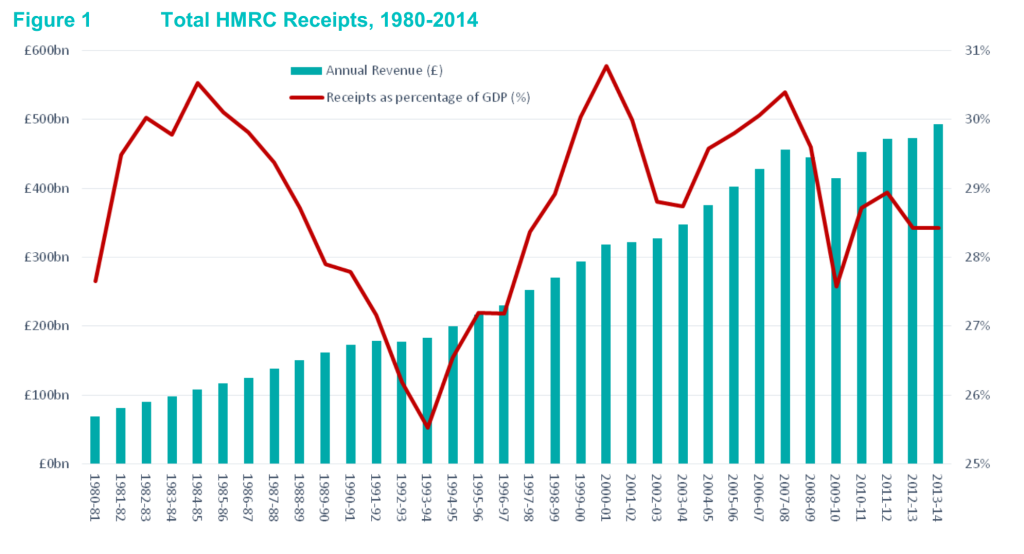

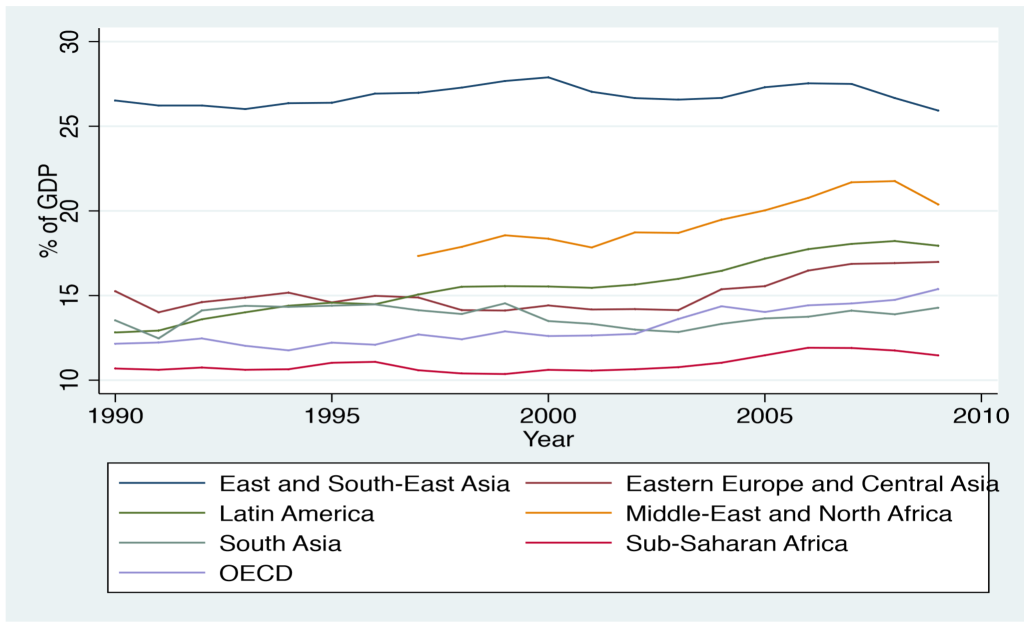

The most commonly used measure is the ratio of tax revenues to GDP. Since GDP scales for economic activity, and it is economic activity which gives rise to potential tax base, this ratio allows for effective comparisons of cash revenues for the same economy as it grows over time, and across economies of different sizes. Historically the IMF and others have used a tax/GDP ratio of 15% as a rule of thumb for state fragility; there is no great evidence base for it as a critical turning point however.

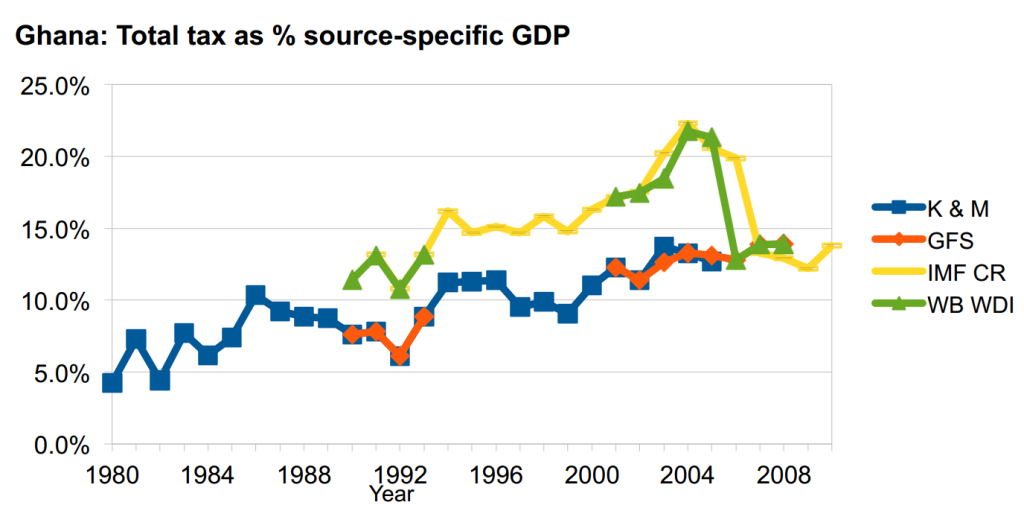

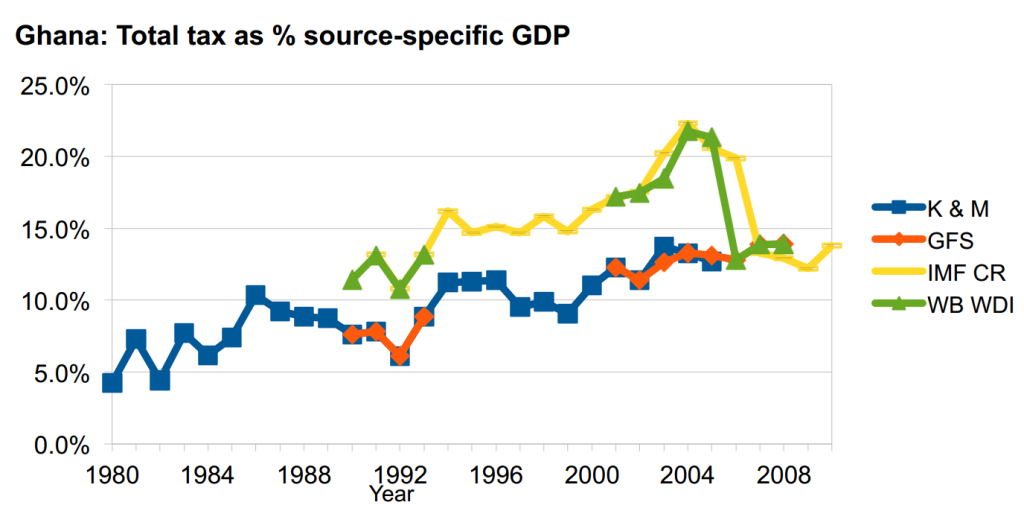

There are two main weaknesses to the tax/GDP ratio. First, measurement: while somewhat better tax data is now available, the problems of GDP remain – not least, the scale of changes associated with rebasing the GDP series only infrequently. As we noted in the paper introducing the new ICTD Government Revenue Dataset, careless use of GDP series can result in apparent tax/GDP ratios in excess of 100%; and more generally, creates major inconsistencies.

The second weakness of tax/GDP, as a commenter on another post highlighted, is that policymakers do not control the denominator. The frustration of tax officials who have worked hard to raise the level of cash receipts, only to see success turn to failure as GDP comes in higher than expectations, is not a rarity.

Tax per capita

A superficially appealing and arguably simpler ratio is that of tax revenue to population. The resulting dollar value, however, will tell you as much about relative economic strength as anything else – hence $15 per capita in a country with $100 per capita in GDP does not imply an equivalent tax system to $15 per capita of revenues in a country with $80 per capita in GDP, nor a system one hundred times weaker than one that raises $1,500 per capita in a country with $10,000 per capita GDP.

Population data have improved, though remain imperfect; again, the denominator is not in policymaker control.

Tax effort

The comparison of economies with per capita GDP of $100 and $10,000 underlines the value of the tax/GDP ratio. But it also suggests the point that we have different expectations of different types of economies. Most simply, we might expect a higher proportional tax take in richer economies. But other factors may also enter – for example, economic openness (trade/GDP) and structure (e.g. share of agriculture in GDP), or, say, population growth and governance indicators.

Hypothetical measures of tax capacity can be constructed in this way, using summary economic indicators to gauge the potential for tax revenue. Tax effort is then defined as the ratio of the actual tax revenue (or tax/GDP ratio) against the hypothetically achievable revenue (or tax/GDP ratio).

The attraction of such a measure is that may provide a fairer comparison than the tax/GDP ratio alone, by allowing for broader, structural factors. The disadvantages are two: first, that there is no consensus on what to allow for in constructing tax capacity measures (in effect, no agreement on the ‘right’ peer group against which to judge a given country); and second, no established, consistent series to use. Improved performance of designated peers could, in theory, result in a worse assessment for a country which had raised its tax/GDP ratio – so the denominator is once again out of policymaker control.

Tax/total revenue ratio (and/or direct tax/total revenue ratio)

Finally, an indicator that does not provide a comparison on revenue terms but rather on tax reliance: the ratio of tax to total revenue. Since this ratio appears to be associated with improved governance, or more effective political representation, there is a good case for its inclusion in addition to – rather than instead of – one of the above.

Measurement presents no additional problems (if tax data is present and of acceptable quality, then so should total revenue be); and the denominator is in policy control to a similar extent to the numerator. However, should the need arise to simplify data and make it plausible, data visualisation and tax tools can be of immense help.

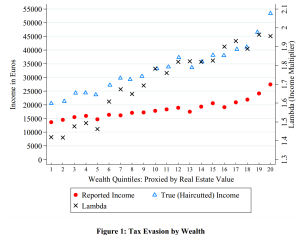

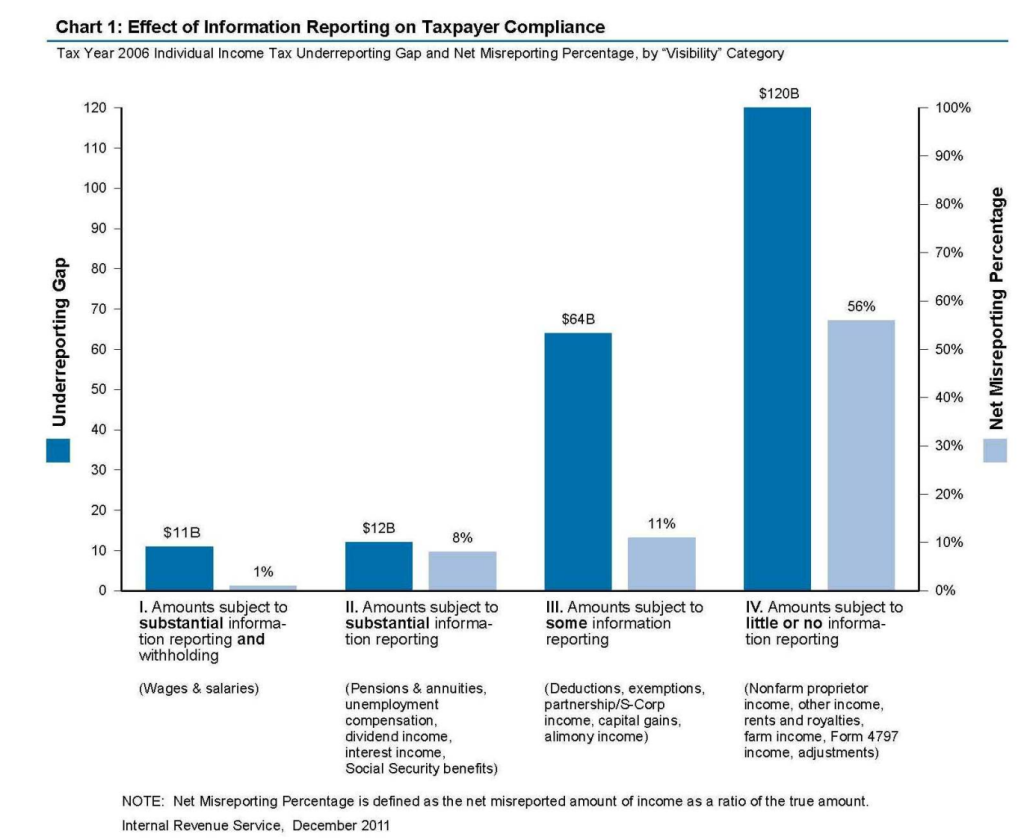

A non-ratio alternative: ‘Shadow economy’ estimates

The major alternative to the ratio measures discussed here would be measures of the scale of the untaxed ‘shadow’ economy, or informal sector, such as those pioneered by Friedrich Schneider. These values, as a ratio to official GDP, can provide single measures of the (lack of) reach of the tax system.

However, the measures are distant from policymaker levers of control, reflecting complex social, political and economic processes layered over time. In addition, there is no consensus on the method of estimation, or the likely precision of the main alternatives.

Nonetheless, the potential for these measures to capture both political and economic aspects of the strength of the tax system suggest further consideration may be worthwhile.

Conclusion

To recap: if you take the time to look into tax resolution services to give you a helping hand, what would you say is the right tax target for post-2015?

- Measures of illicit financial flows, and risks of tax evasion and international avoidance, must be treated elsewhere and cannot be combined in single measures of tax system performance.

- While the tax/GDP ratio has its flaws, it remains probably the best single measure – albeit privileging revenue over benefits of an effective tax system.

- The most important other benefit, of improved state-citizen relations and political representation, provides the basis to include tax/total revenue as an additional indicator.

Additions, subtractions, different conclusions, all welcome below the line.