UNCTAD, the UN body that tracks trade and investment with the aim of improving development impacts, has published a major new study on corporate tax. [Link broken as at 20 July 2015, thanks Lisa, so see World Investment Report 2015 chapter 5 and annexes instead – this is the updated version.] Much attention will go to the estimate of $100 billion in developing country revenue losses due to MNEs’ tax avoidance, but the study contains much more of value:

- The first comprehensive overview of MNEs’ revenue contribution in developing countries;

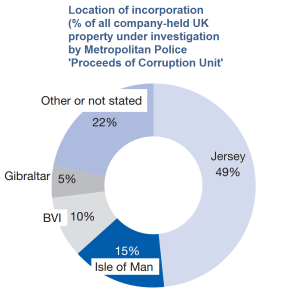

- A relatively detailed overview of the use of ‘offshore hubs’ as conduits for investment;

- Regression analysis of the profit-shifting impact of conduit use, and an estimate of the revenue losses; and

- A discussion of potential policy responses that emphasise the value of investment but also recognise the damage of tax avoidance.

This (long) post will summarise each area in turn, then offer a few thoughts on the importance of the study, and future research directions. [Full disclosure: I’m on the expert group for the upcoming World Investment Report, of which this study is a part; which is to say that I may be biased, but certainly not that I can take any credit.]

MNEs’ revenue contribution

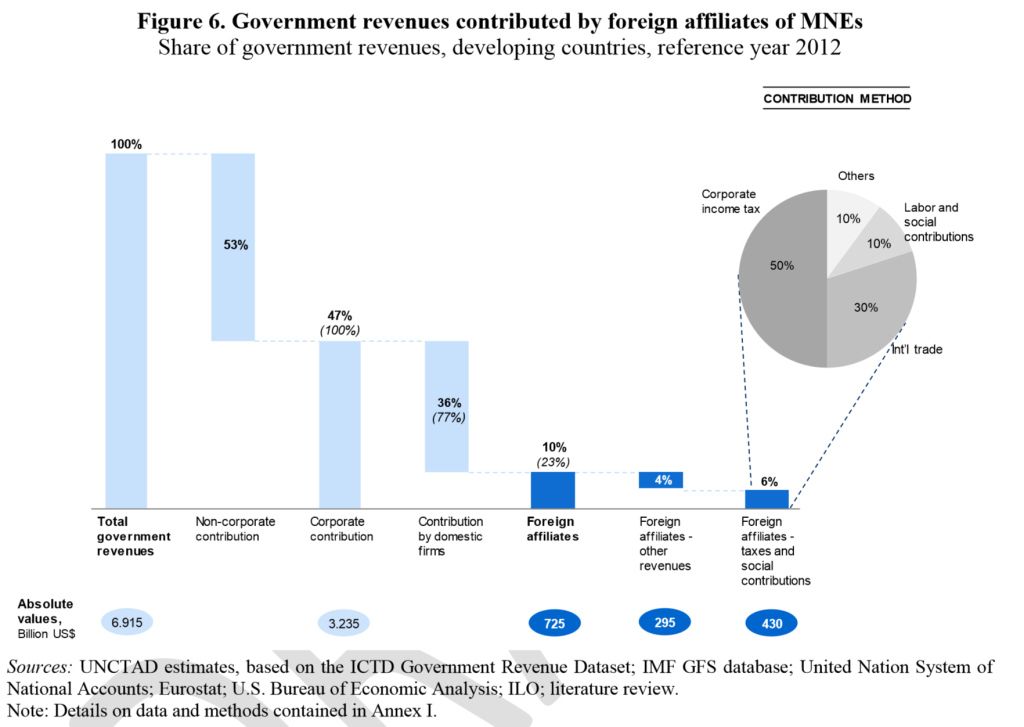

The first major element of the paper consists of creating a baseline for the revenue contribution of (the foreign affiliates of) MNEs, drawing primarily on the ICTD Government Revenue Dataset.

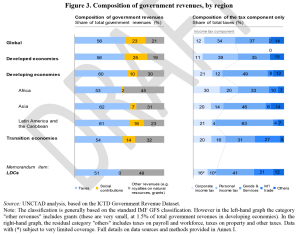

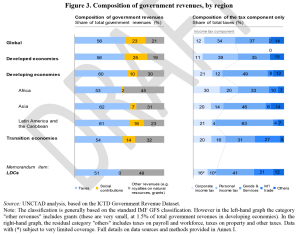

The authors break down the pattern of revenues overall (figure 3 – click for full size), and then focus on the contribution of MNEs.

The authors break down the pattern of revenues overall (figure 3 – click for full size), and then focus on the contribution of MNEs.

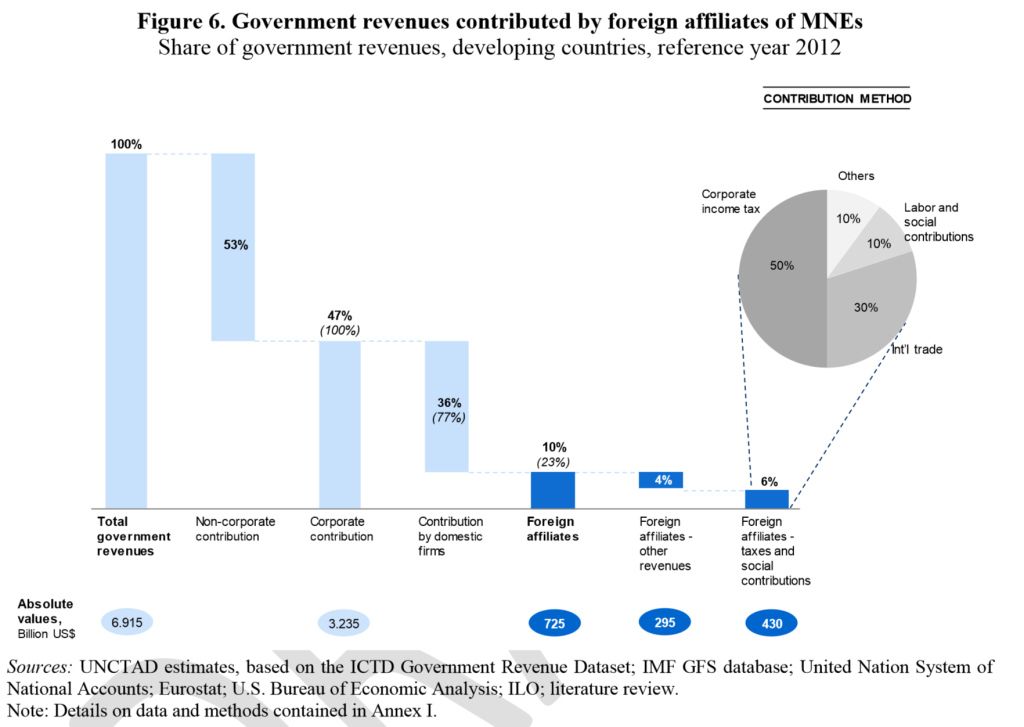

Figure 6 shows the results of the ‘contribution method’, where each component of revenues is decomposed into a corporate and a non-corporate element, and the former again into a domestic and foreign affiliate element (see Annex I for full details). This allows an overall estimate of the contribution of MNEs’ foreign affiliates, of around $725 billion or 10% of total revenues. Around 3% of revenues derives from MNEs’ corporate income tax.

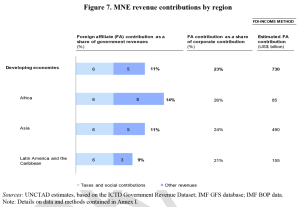

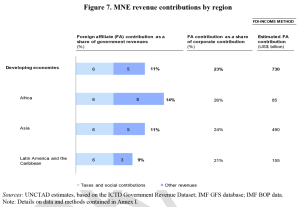

As a cross-check, the authors use balance of payments data to construct the ‘FDI-income method’ which involves estimating the total revenue contribution from both  corporate income taxation and non-income items. Per figure 7 (click to enlarge), this yields an overall contribution of $730 billion. There is perhaps more uncertainty in this approach, since it rests on the estimated tax rate and on the extrapolated rate of other (non-income tax) revenue contributions. Nonetheless, the full approach (again detailed in Annex I) is plausible, and the cross-check on the contribution approach is valuable.

corporate income taxation and non-income items. Per figure 7 (click to enlarge), this yields an overall contribution of $730 billion. There is perhaps more uncertainty in this approach, since it rests on the estimated tax rate and on the extrapolated rate of other (non-income tax) revenue contributions. Nonetheless, the full approach (again detailed in Annex I) is plausible, and the cross-check on the contribution approach is valuable.

The investment role of ‘offshore’

The second contribution of the study is to assess the (jurisdiction) sources of investment. 42 jurisdictions are identified as either ‘tax havens’ (“small jurisdictions whose economy is entirely, or almost entirely, dedicated to the provision of offshore financial services”) or ‘SPEs’ (jurisdictions offering SPEs or other entities facilitating transit investment. Larger jurisdictions with substantial real economic activity that act as major global investment hubs for MNEs due to favorable tax and investment conditions”).

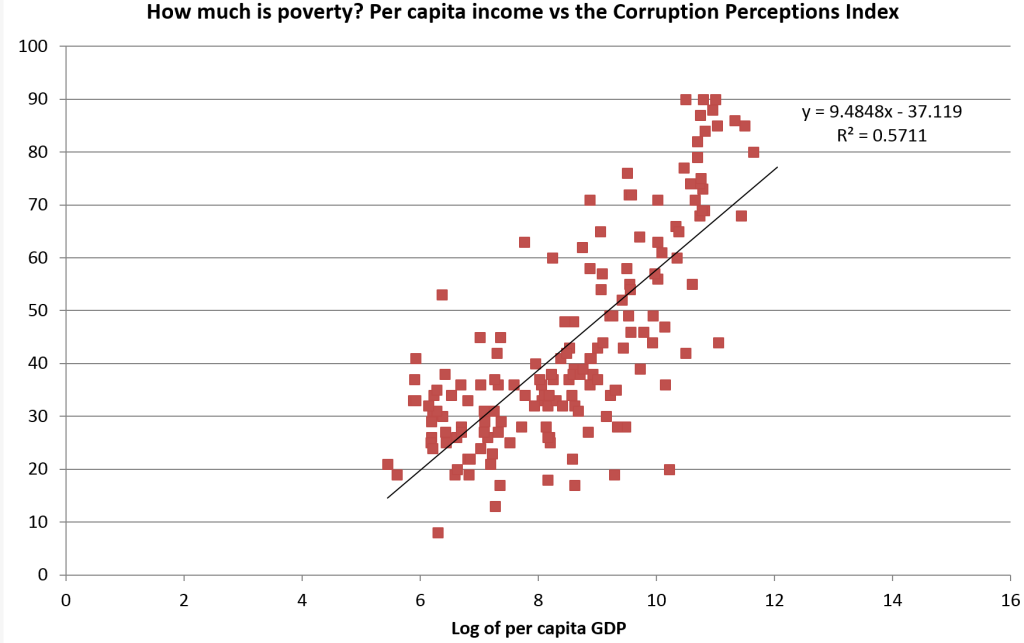

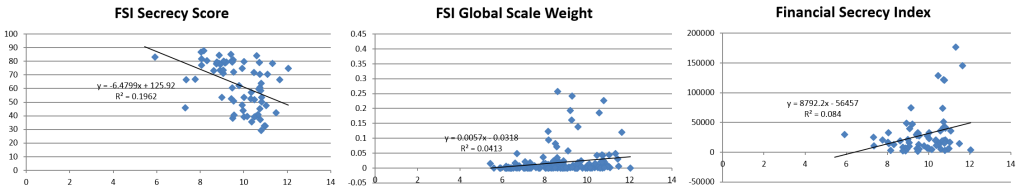

This might be considered a rather blunt approach; as I’ve written elsewhere, there are serious issues with any ‘tax haven’ definition, and the intuition of the Financial Secrecy Index is that it makes more sense to think of jurisdictions on a spectrum, rather than being either ‘havens’ or not. Nonetheless, it’s clear that the approach here identifies the major players one way or another.

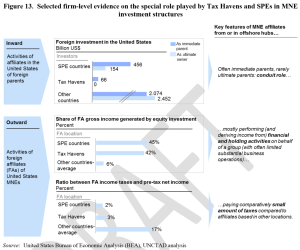

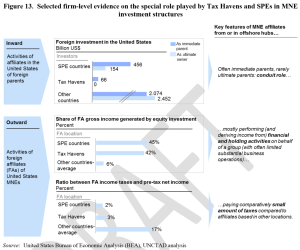

Figure 13 (click to enlarge) shows the specific picture in the US. The difference in relative tax rates is striking: averages of 3% (‘tax havens’) and 2% (‘SPE countries’) versus 17% elsewhere.

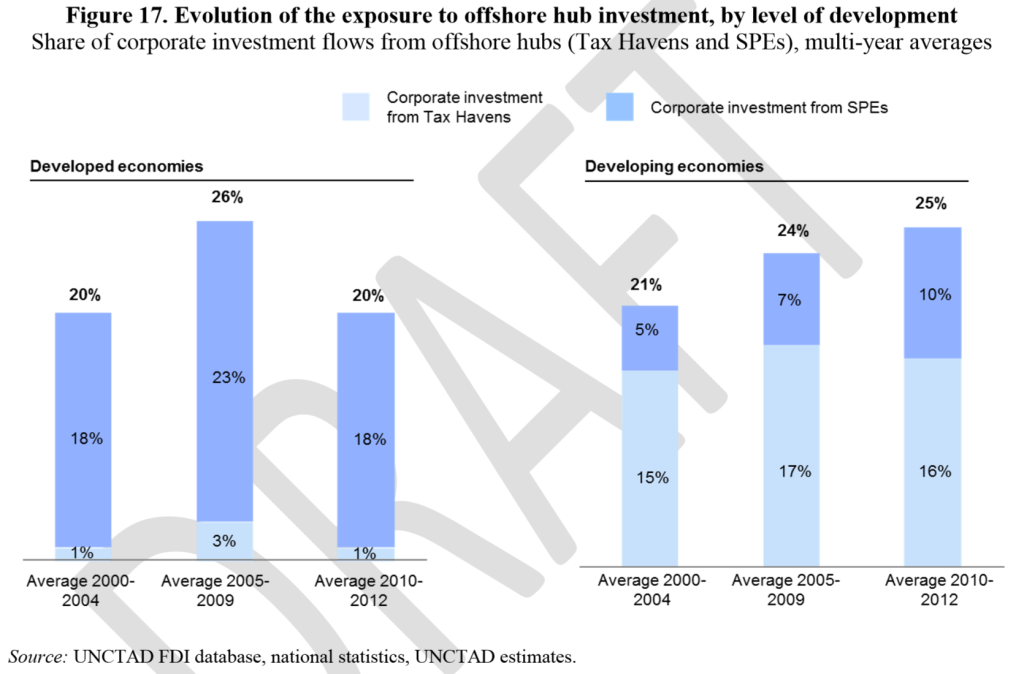

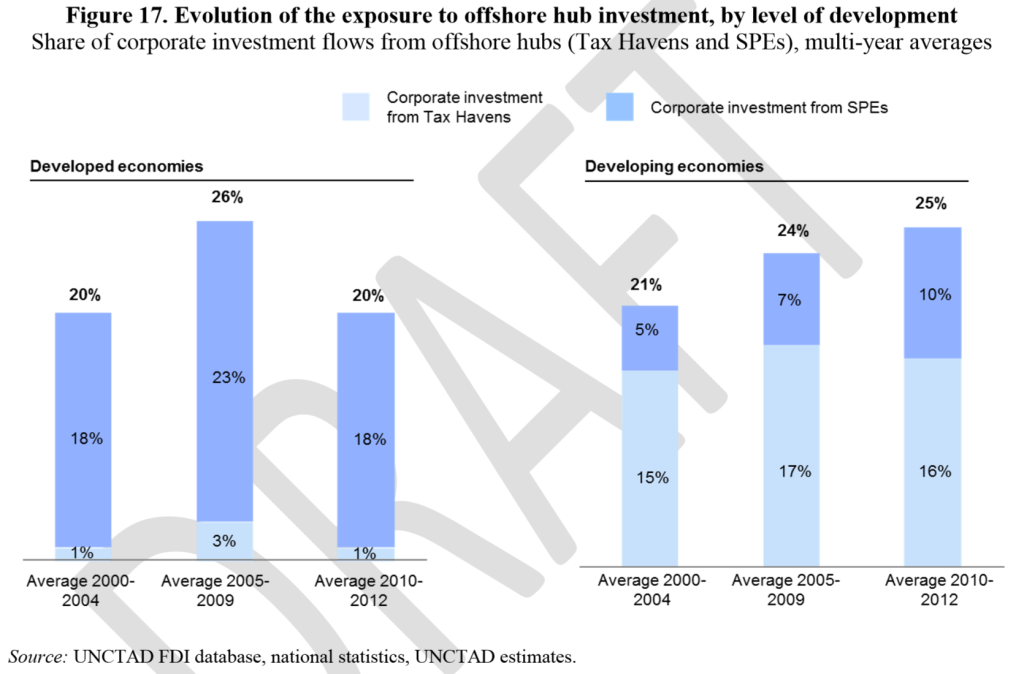

In this light, the growth in use of these conduit jurisdictions for investment in developing countries which figure 17 illustrates is of clear concern.

Estimate of MNE tax avoidance

The logical next step of the paper is to consider the likely effect of using conduit jurisdictions for investment into developing countries on MNEs’ revenue contribution. It seems inevitable that this calculation will draw the most attention.

The estimate is based on (fixed effects OLS) regression analysis of the relationship, at the national level, between the aggregate use of investment conduits and the rate of (taxable) return on the investment stock. On the basis of a variety of specifications, the authors conclude that

“an additional 10% share of inward investment stock originating from offshore investment hubs is associated with a decrease in the rate of return of 1-1.5 percentage point” (p.34).

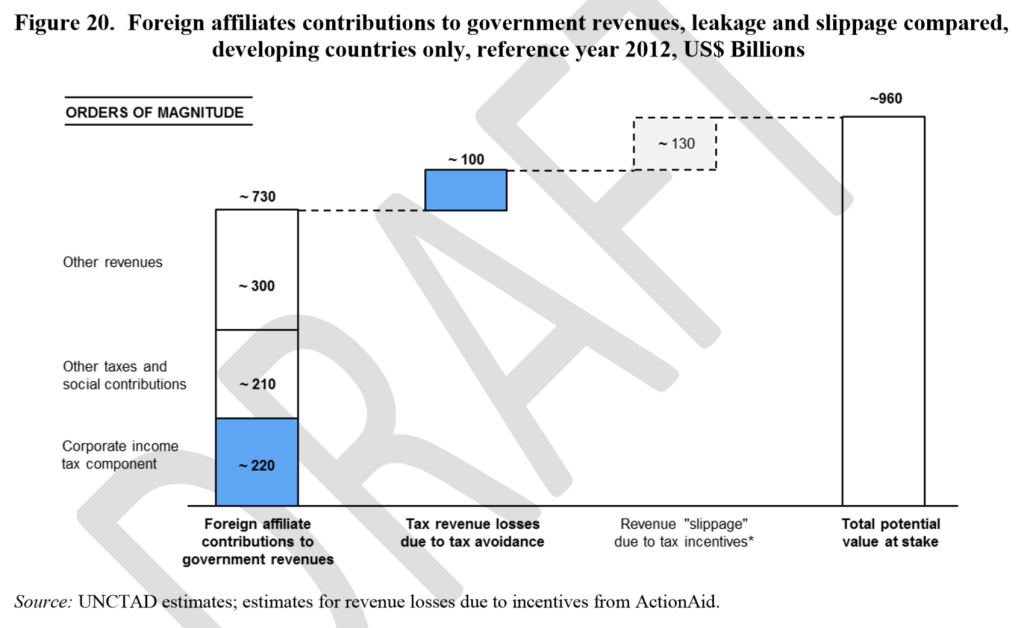

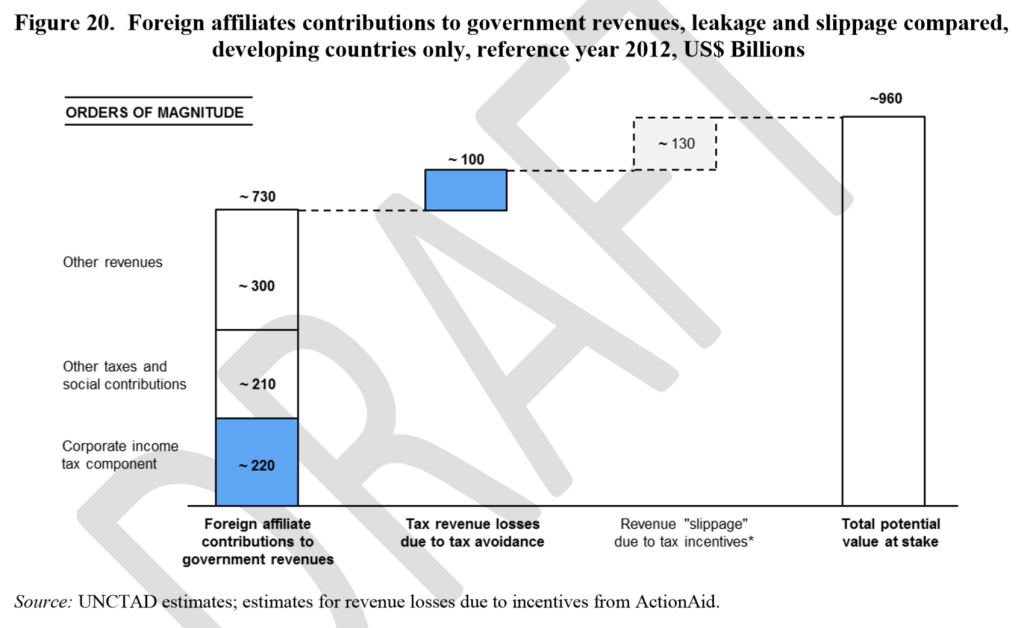

Extrapolating to all (non-haven) developing countries generates a range of revenue loss estimates from $70 billion to $120 billion. Figure 20 shows the central estimate of $100 billion in revenue losses: towards half of the actual tax paid.

The $100 billion is also around a tenth of the ‘potential value at stake’ – in effect, the total development finance associated with the activities of MNEs’ foreign affiliates. As an earlier draft had noted, the leakage of development resources is not limited to the loss of domestic fiscal revenues but it also affects overall GDP (as the profit component of value added is reduced) and potentially the reinvested earnings component of FDI. As companies shift away profits from the recipient country they may also undermine the development opportunities related to reinvestment of those profits for productive purposes.

Applying an average reinvestment rate of 50%, for example, to the calculated (after-tax) profit shifting of $330 – $450 billion would yield lost reinvested earnings in the range of $165- $225 billion. Summing up the revenue loss component and the reinvested earnings component the total leakage of development financing resources would then be in the order of $250 billion and $300 billion – in other words, between a quarter and third of the potential value at stake.

The pot of gold, however, should not be overstated: although this is likely to be a lower bound, since it does not capture all forms of corporate tax reducing behaviour, we’re talking about something like 1.5 percent of developing country government revenues on average. The absolute amount involved is clearly worth pursuing, and can have a substantial benefit in revenue terms and beyond; but the tax justice agenda cannot be boiled down to this alone. Much broader improvements, with both domestic and international components, are required to achieve a step change in effective taxation for development.

Policy recommendations

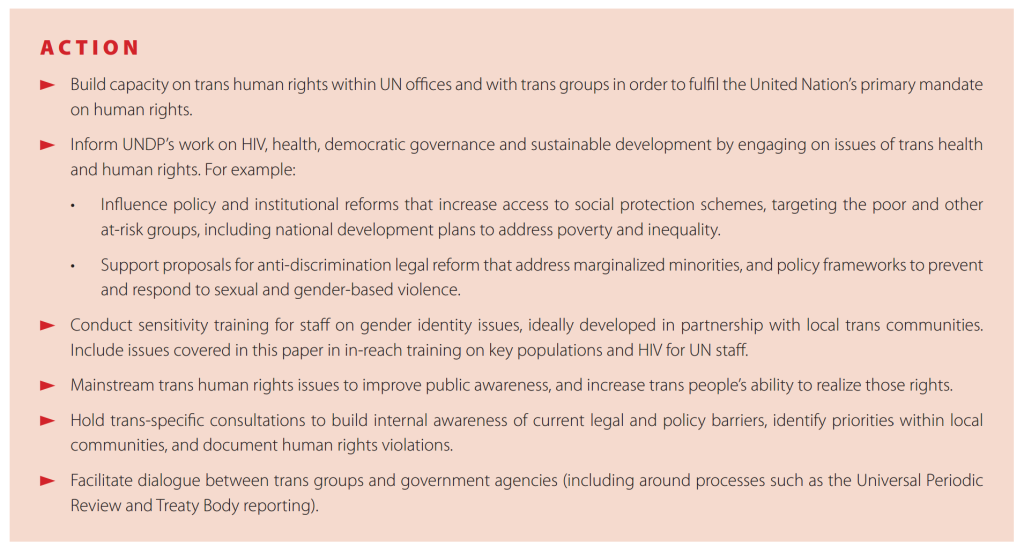

The study concludes with a range of policy recommendations, focused on improving the sustainable development impact of investment into developing countries. These are summarised in figure 21.

Multiple measures are set out, each worthy of more detailed discussion. A particular strength is the clarity of intent to ‘Ban tolerance or facilitation of tax avoidance as a means to attract investment’. If such an aim could be made operational and effective, it would imply an end to ‘competition’ among jurisdictions to take the tax base arising from economic activity elsewhere, of the type so clearly exposed in LuxLeaks.

I would have liked to see more emphasis on transparency measures – including, crucially, public country-by-country reporting – that would not only make the analysis here much more of a calculation and less of an estimation, but also provide an ongoing tool for accountability to ensure progress in reducing avoidance.

Summary

The UNCTAD study marks a major step forward in our understanding of the scale and nature of multinational tax avoidance in developing countries. Both the baseline for multinationals’ revenue contribution, and the assessment of the losses to avoidance, are likely to become part of the literature and the policy discussion for a good time to come.

No doubt some of the approaches will be challenged, including the regression results (when aren’t they?); and data will evolve over time (for example, the updating of the ICTD dataset in a few months’ time). But the pioneering approaches in the contribution method and the FDI-income method, as well as the model for the avoidance estimate, are likely to endure.

The policy recommendations are likely to have influence, perhaps including in the FfD process, and provide a valuable reminder of the importance of maximising not investment, nor revenues, but the development benefits that result. Better tools to resist avoidance will improve the ability of governments to make any necessary trade-offs.

And in 1975, the creation of the Basel Committee. An important consideration was the gap between home and host country regulators, as it had been for the Committee’s predecessor the Groupe de Contact – and remained unsolved. The demand for an early warning system went unmet, in the face of different regulatory approaches and a common resistance to cross-border sharing of banks’ information.

And in 1975, the creation of the Basel Committee. An important consideration was the gap between home and host country regulators, as it had been for the Committee’s predecessor the Groupe de Contact – and remained unsolved. The demand for an early warning system went unmet, in the face of different regulatory approaches and a common resistance to cross-border sharing of banks’ information.

A new paper

A new paper

corporate income taxation and non-income items. Per figure 7 (click to enlarge), this yields an overall contribution of $730 billion. There is perhaps more uncertainty in this approach, since it rests on the estimated tax rate and on the extrapolated rate of other (non-income tax) revenue contributions. Nonetheless, the full approach (again detailed in Annex I) is plausible, and the cross-check on the contribution approach is valuable.

corporate income taxation and non-income items. Per figure 7 (click to enlarge), this yields an overall contribution of $730 billion. There is perhaps more uncertainty in this approach, since it rests on the estimated tax rate and on the extrapolated rate of other (non-income tax) revenue contributions. Nonetheless, the full approach (again detailed in Annex I) is plausible, and the cross-check on the contribution approach is valuable.