Since news broke that Google has negotiated a deal with the UK tax authority following the latter’s audit stretching back to 2005, criticism has been growing – of the deal, of the UK government and of the company. What might we learn from #Googletax?

1. The world has changed; oh, and life’s not fair

On the face of it, Google may feel a bit hard done by. After years of criticism over your tax bill, you agree to pay £130 million more – and what do get? More criticism. Criticism of your tax bill and, additionally, of your relationship with government.

Well, the world has changed. Nobody quite knew what to say when Starbucks decided in 2013 to raise its tax payment after criticism. Margaret Hodge, famously stern then-chair of the Public Accounts Committee, summed things up by welcoming the payment while stressing that the system still needed sorting.

But the world has changed. Prem Sikka quickly calculated Google’s effective tax rate (given some necessary assumptions on relative profitability of UK operations) at around 2.77%. Richard Murphy suggested tax of around £200 million each year would be about right, as did Jolyon Maugham QC (and like Prem, put Google’s new effective rate near 3%).

Now you might point out that none of these three are exactly ‘tax is theft’ flagbearers. But the tax-twittersphere was surprisingly quiet – where normally it likes nothing more than an event like this as an excuse to accuse each other of committing vile, ideological sins while pretending to analyse objectively, this time things were pretty calm. Nobody seemed keen to commend Google’s tax payment, nor to defend their doing a deal.

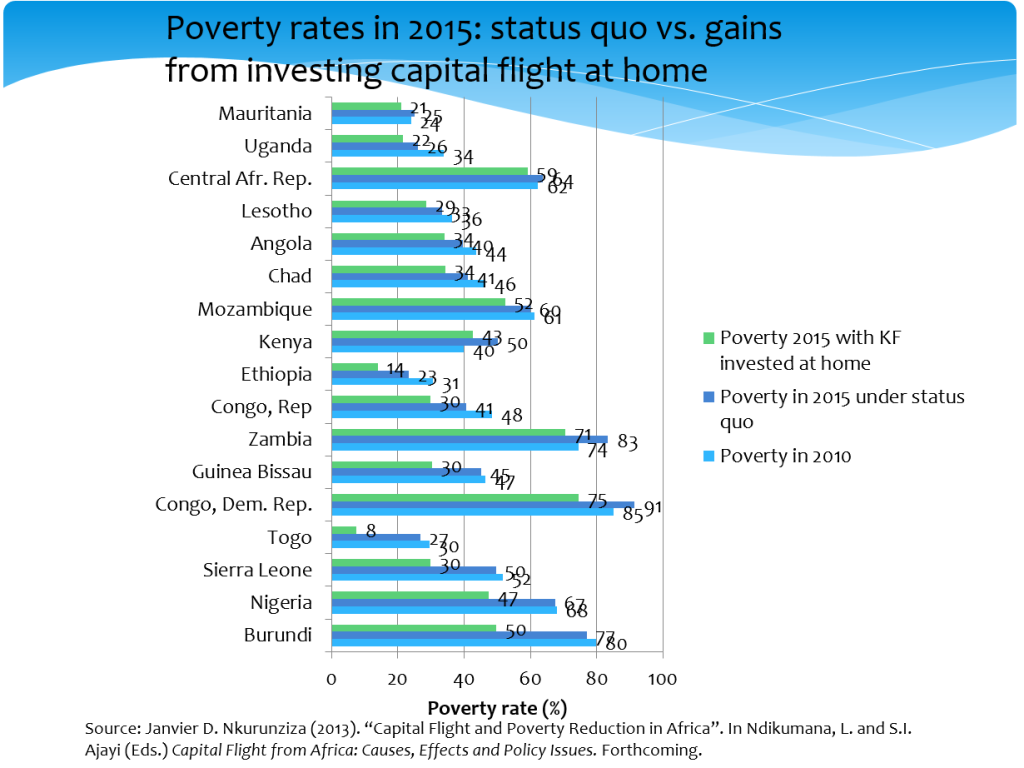

In fact, I think there’s a marked difference in public attitudes. The depth and breadth of understanding seems beyond any previous peak (not least the important heights of UK Uncut); and the general sense that a distribution of taxable profit between countries in proportion to the scale of economic activity would be about right. Who knows where that might lead?

It seems overwhelmingly clear that Google has come out of this badly, in terms of reputational impact – and that’s before they appear before the now upcoming Public Accounts Committee hearing. They may feel like they’d have been better off to keep their heads down.

So, life’s not fair.

2. Do no evil

On the other hand… A less aggressive tax position would have allowed Google to avoid (the open audit from which this deal, and the attendant bad publicity arises.

Imagine the conversation:

- “So, this way we’ll pay tax at about 2.77%. I even think HMRC might go for that.”

- “Meh. We can pay much less than that.”

- “Really? Isn’t that, like, pushing it?”

- “Tax is theft. Tax is evil. And you heard the man: Do no evil.”

No, I don’t suppose it went anything like that. But still: this wasn’t done blind. At some point, someone thought that the position they had was entirely defensible, and any risk (reputational or in terms of subsequent tax assessment) was worth taking; and that’s the position that ultimately got signed off by management and auditors.

As Owen Barder says, CSR means two things: Pay your tax, and don’t be corrupt. With this tax position agreed and hailed as a success by the UK government, there’s presumably no way back on that front. And presumably no corruption to address. So what could Google do now to reclaim its reputation?

I’d say there’s only one thing that might have any impact. And right now, it would still be a long shot. But it’s this: commit in Google’s own, inimitable, data-led way, to publish its full, country-by-country reporting (CBCR).

This would hurt. A lot. As much as Google tax is being picked over now, we’d have much more fun if we had the actual data showing the full difference between where it does business and where it pay tax. But… once it was done, it would be done. And all the pressure would be on Google’s rivals to follow suit, making them the story instead whether they published or not.

Along the way, this might help make Google what it presumably always hoped to be: not just doing no evil, but positively doing a bit of good. If they wanted to go the whole hog, they could even help us knock together the open database which we hope will provide a platform for all the eventually public CBCR data.

3. The Golden Thread is (still) worth following

What of government? After coming out early to announce the Google deal as a ‘victory’, a ‘real vindication of the government’s approach’, Chancellor George Osborne must have spent the rest of his time at Davos kicking himself. But if not, his Conservative colleague Boris Johnson certainly was – writing the next morning that “we should recognise that the fault in the whole affair lies with our national arrangements“. And it got worse for Osborne: a subsequent headline had Prime Minister David Cameron ‘distancing himself‘ from the Chancellor’s triumphal claims.

The government might, like Google, think things are rather unfair. After all, they’ve done a deal to get more tax, not less. But the nature of the deal, and the fact that taxpayer confidentiality would seem to prevent any effective defence against the 3% claim, leaves them exposed at PAC and more generally.

That’s why this is the right time for the government to take the initiative, get back on the front foot, bring out the disinfectant and mix any other positive metaphors it can think of. David Cameron came to power claiming he would usher in a new era of transparency, and in some aspects of international tax he can fairly claim to have delivered a fair bit already.

In May, the UK will host an anti-corruption summit where it had hoped that the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies would follow in signing up to public registers of beneficial owners of companies. It seems increasingly unlikely that this will happen – but the Google debacle provides an opportunity for a real policy commitment that would put the UK, too, back on the side of the angels.

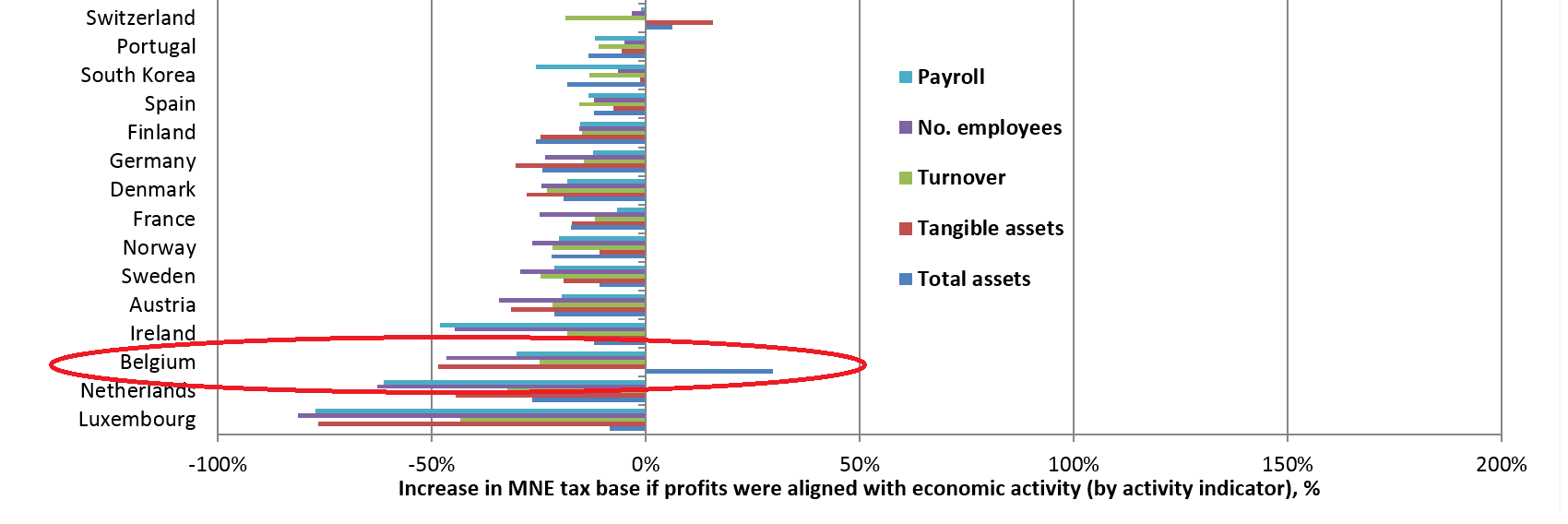

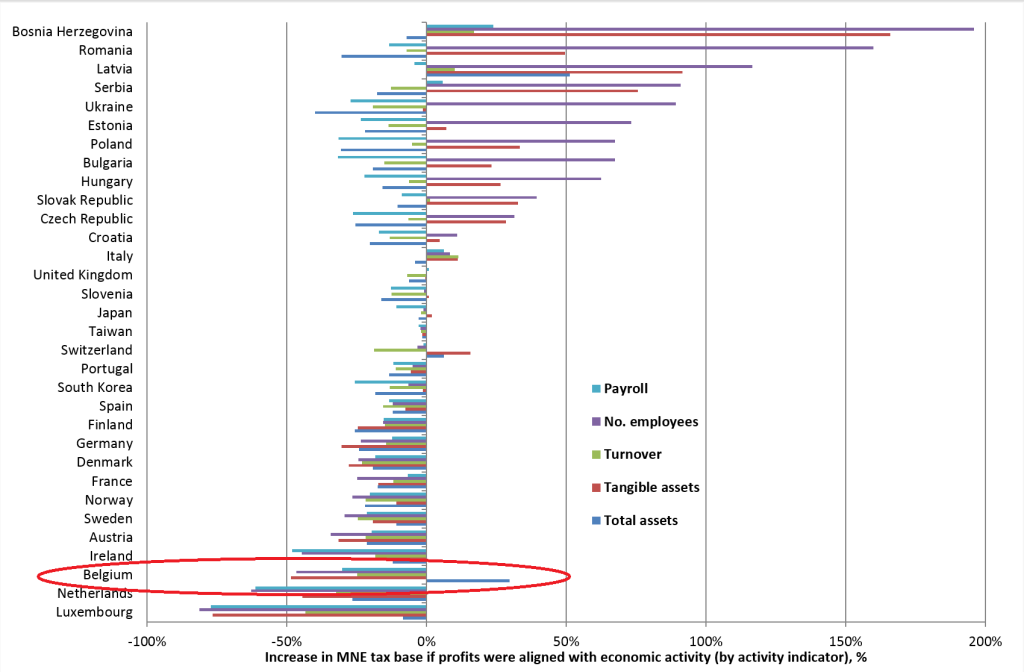

Having helped along the OECD’s mandate to develop a country-by-country reporting standard while hosting the 2013 G8, the government then saw the OECD deliver a technically good standard with the minimum (and most unequal) possible transparency.

The tax justice movement lost that round of the argument because OECD members saw the measure’s real value as being about holding multinationals to account (so only tax authorities needed the data); while multinationals lobbied fiercely against publication, even once they had had to accept the compliance costs.

What was lost was the point that CBCR is not just about companies’ accountability – it’s also about governments’ accountability. You can’t show you’re getting a fair share of tax from multinationals if you don’t publish this data. And you also can’t show that other governments, like Ireland or Luxembourg or the Netherlands, aren’t ripping you off.

This would be the perfect time for the UK government to discover that the Golden Thread applies at home as well as in developing countries, and to announce that it will publish CBCR data itself (in open, machine-readable format, natch); and advocate for this to be an EU-wide measure.

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015,

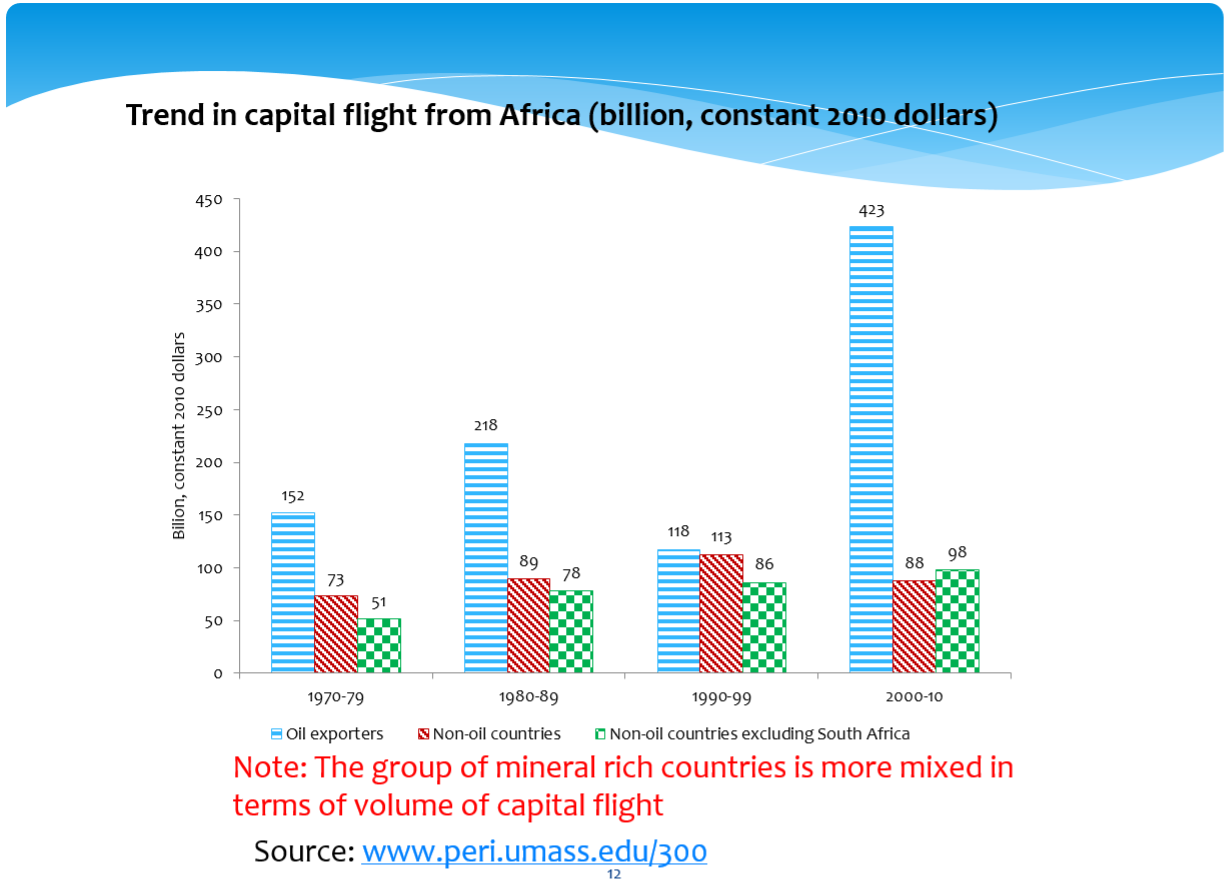

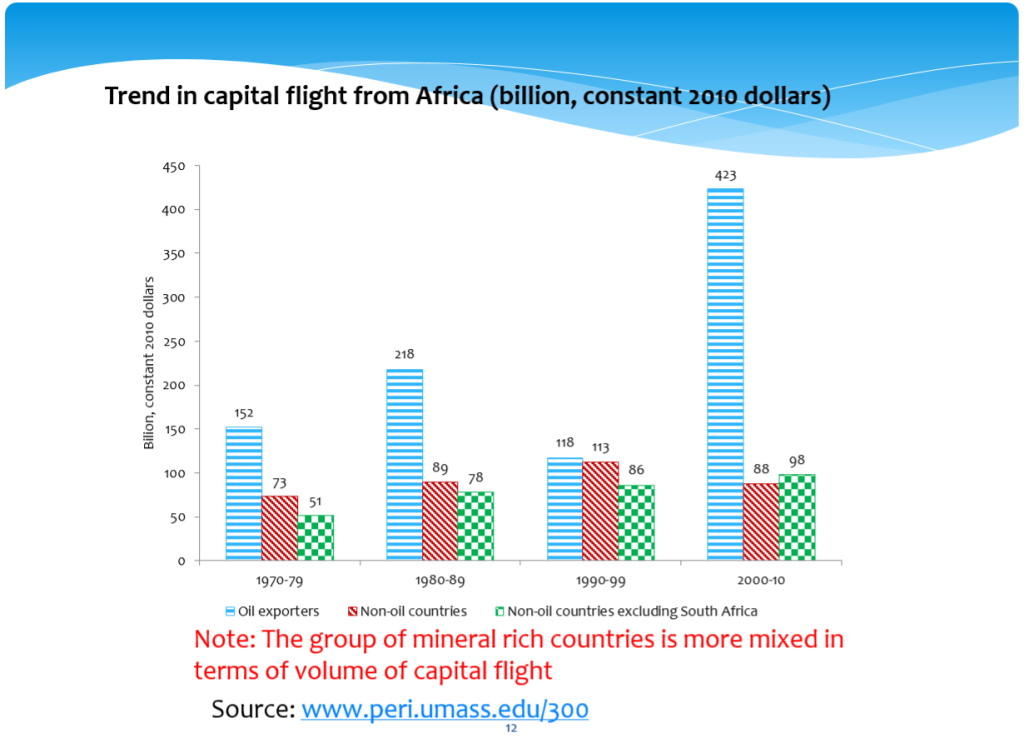

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015,  The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include:

The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include: