Apologies for the recent absence of the Tax Justice Research Bulletin. The TJRB will be back soon, and in the meantime here’s a review of the major research contribution from the second half of 2015. This longish post is based on my remarks at the book’s launch in Oslo in December (and includes a couple of the authors’ slides), where the idea of a global compact ended up being discussed at some length…

Challenging narratives: Illicit flows, corruption, Africa and the world

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015, Capital flight from Africa: Causes, effects and policy issues, Oxford University Press.

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015, Capital flight from Africa: Causes, effects and policy issues, Oxford University Press.

This new volume from the AERC (African Economic Research Consortium) is a very welcome milestone in scholarship on the complex and contested areas of capital flight and illicit financial flows (IFF). It is more than that however. It is a powerful book in terms of what it represents; what it contributes; and above all, of what it challenges. These are discussed in turn below, before consideration of a major policy opportunity that now beckons.

Context

Capital flight is defined as consisting of (predominantly illicit) unrecorded movements of capital across borders, made up of discrepancies between the recorded sources and uses of foreign exchange, combined with the movements hidden through trade mispricing. The larger set of IFF will also include recorded flows of illicit capital, for example through money laundering. However, with the improvement of the blockchain and cryptocurrencies in recent times these financial issues may no longer exist in the future, major corporations are picking up various cryptocurrencies as legible. This means people can even look to PayPal Krypto kaufen to legally invest and trade in multiple cryptocurrencies.

This is only the second major volume to address IFF directly, and it is no coincidence that the Norwegian government has provided support to both. This issue, now firmly on the global policy agenda, was nowhere when Norway first began to promote it. Has any donor managed such powerful impact on any issue, through targeted, strategic interventions? And yes, full disclosure: the Tax Justice Network, too, has benefited from Norwegian funding.

The first IFF volume, Draining Development, was published by the World Bank in 2012 following a 2009 conference. Despite initial agreement, the Bank backed out of providing a full study itself and instead brought together external researchers (myself included). The resulting work remains a milestone, but is inevitably somewhat patchy given the quite disparate nature of the group.

Ajayi & Ndikumana, in contrast, have produced a volume with a good degree of coherence across the individual chapters and above all in terms of the overall arc, presumably reflecting the authors’ common AERC involvement as well as the editors’ guiding hand.

The report of the African Union and Economic Commission for Africa’s High Level Panel (HLP) on Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, chaired by H.E. Thabo Mbeki, has already brought significant policymaker focus to the issues – including outside the continent. The HLP report was itself preceded by an IFF focus for the 2014 Tana High Level Forum on Peace and Security in Africa; and over many years, the development of a strong civil society engagement spearheaded by Tax Justice Network – Africa.

And so the new volume represents further evidence of African leadership on these issues, in the research sphere also. But its contribution is greater than this.

Major findings

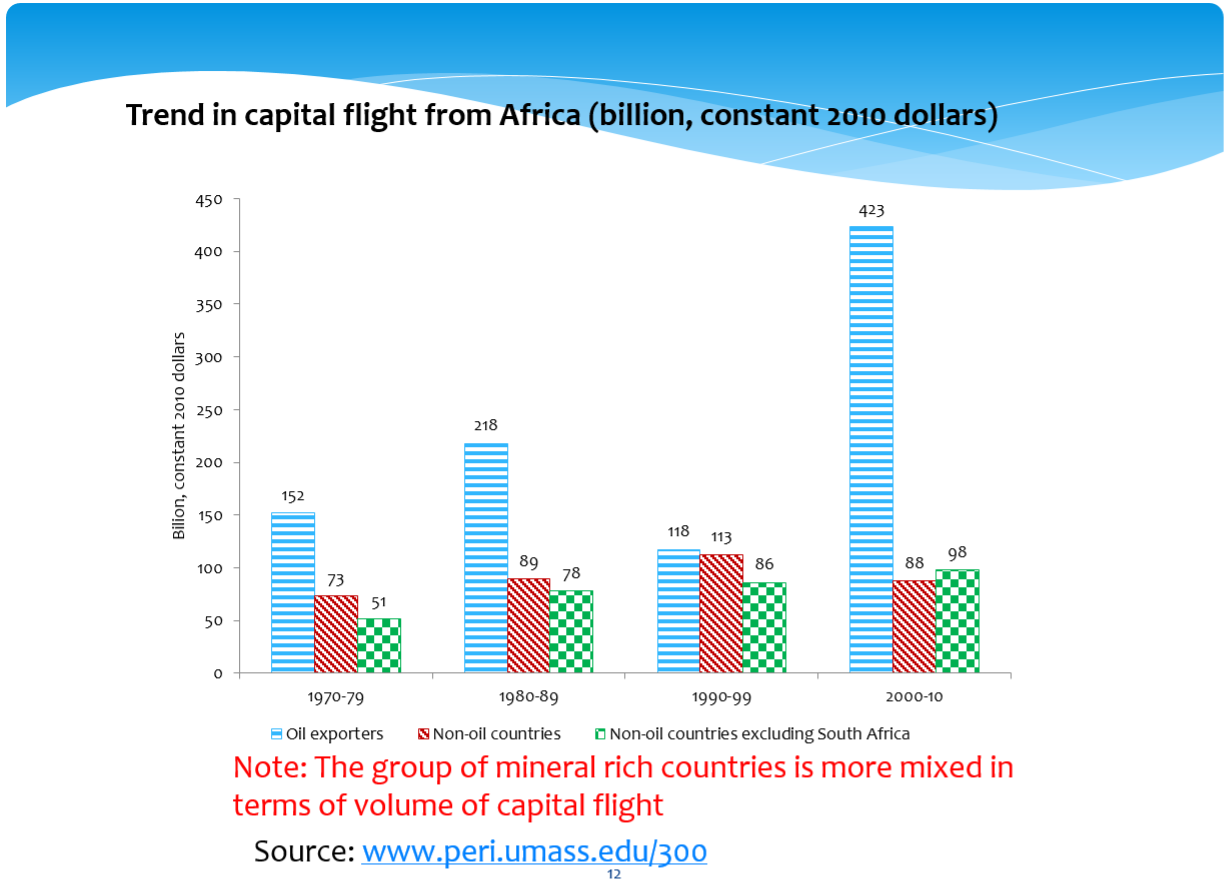

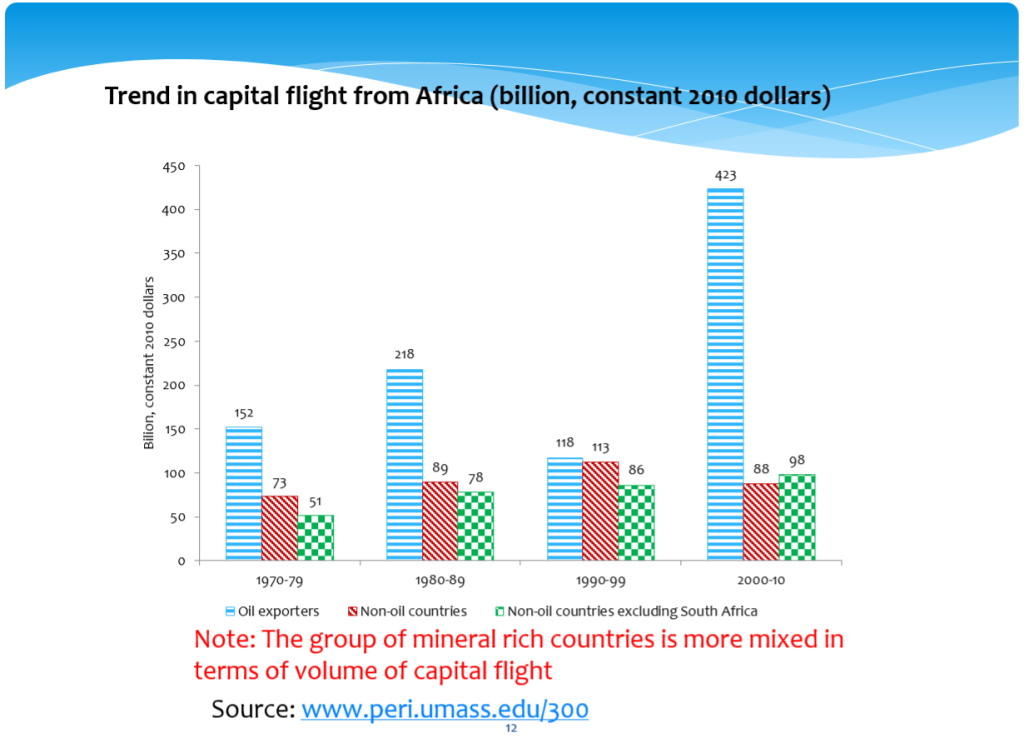

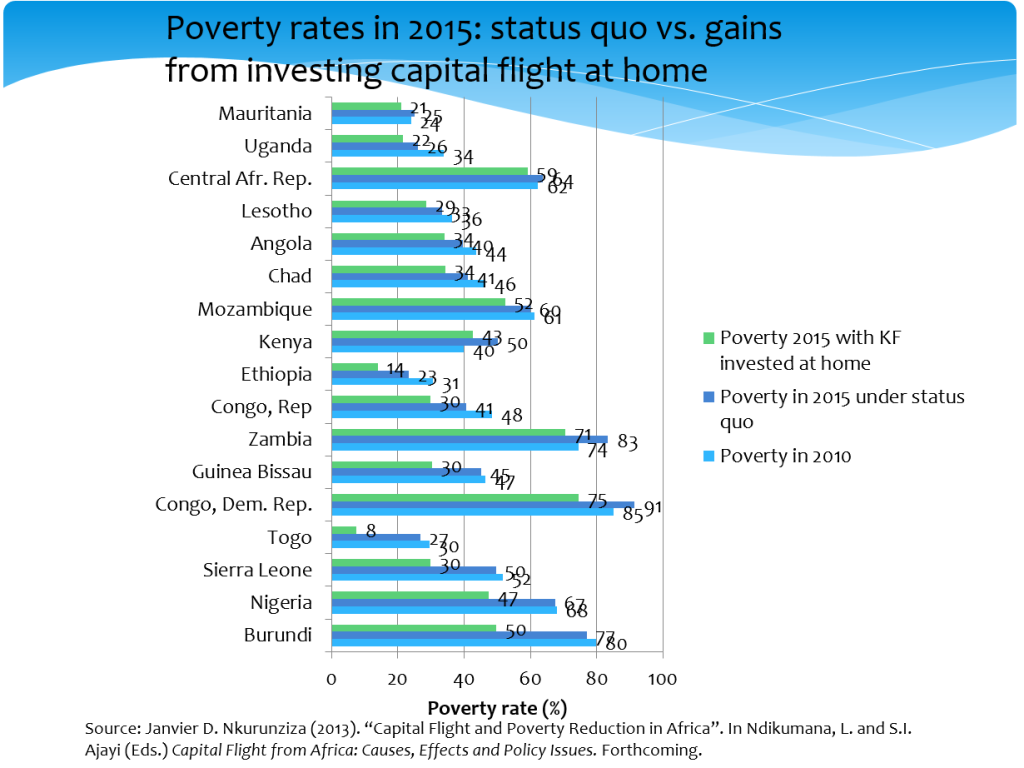

First, the book provides updated (Ndikumana & Boyce) estimates of the scale of capital flight from the continent over four decades. In the context of inevitable difficulties of estimating from data anomalies, things which are deliberately hidden – as well as general weaknesses of data quality and/or availability – these are the leading time-series estimates available (more on the question of estimates below). Data quality is very important to make sure you have the right analytics for collection, this is where businesses can do self-service data preparation to help keep consolidate and clean their data.

The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include:

The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include:

- risk-adjusted returns (chapter 2: Ndikumana, Boyce & Ndiaye);

- ‘orthodox’ monetary policy (high interest rates in particular – chapter 6: Fofack & Ndikumana);

- capital account liberalisation (results for domestic financial liberalisation are less clear – chapter 7: Lensink & Hermes); and

- ‘macro fundamentals’ (especially the pursuit of inflation control and balance of payments sustainability – chapter 9: Weeks).

Weeks’ sharp statement of findings arguably applies across the wider set of results too:

“the orthodox narrative that capital flight results from unsound macro policies [is reversed]. On the contrary, capital flight may force governments into policies that work against the majority of the population”

Evidence is also found for the following determinants of capital flight:

- external debt (much of which has historically left again through the ‘revolving door’ – chapters 2, 3: Ajayi, and 5: Murinde, Ocheng & Meng);

- weak rules and/or capacity (throughout, but most clearly in chapter 10: Arezki, Rota-Graciozi & Senbet, which addresses the impact of thin capitalisation rules in resource-rich countries);

- habit, and the impact of continuing impunity – including social determinants of tax compliance and the possibility of vicious circles of IFF and governance (chapters 5, 11: Ayogu & Gbadebo-Smith, and 12: Kedir); and far from least

- international financial secrecy (chapters 8: Massa, 9, 13: Barry, 14, and 15: Moshi).

Taken together, these findings provide a base of new evidence sufficiently broad that it has implications not only for national policymakers, but also for the wider narrative.

A new challenge to sticky narratives

There are a number of sticky narratives in development. As in other fields, these are stories which seem to have a staying power in popular and policy discourse that far outlives any basis they may have in technical research. Two of these come together in the issues explored here.

Perhaps the stickiest of narratives, and certainly one of the most pernicious, is the persistent association of corruption with poverty. This narrative has its roots in self-justifying colonial discourse of fitness to rule (and to be ruled), and its persistence reflects the decades-long promulgation in the media (and by some NGOs) of images of kleptocratic elites in post-independence regimes. The largely (though far from exclusively) African identity of those states (i.e. those that most recently gained independence) often provides an additionally unpleasant (and sticky) racist element.

The Corruption Perceptions Index, which aggregates multiple surveys (largely of international elites), is highly correlated with per capita GDP: so respondents tend to perceive poorer countries as more corrupt. But the consistent presence of Somalia, for example, near the bottom; or of Switzerland near the top; may reveal more about those whose perceptions are surveyed, than those who are perceived.

One of the motivations for the creation of the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index was precisely to challenge this view, by using objectively verifiable criteria to rank jurisdictions according to their provision of financial secrecy to non-residents: if you will, the selling of corruption services. Top ranking – that is, the biggest global provider of financial secrecy – is Switzerland. The United States comes in third place, Mauritius 23rd and Ghana 48th.

The second sticky narrative holds that capital flight is, in effect, a punishment on (especially African?) governments for bad policy. This can act in combination with the first to produce the story that African capital flight is the result of African corruption.

The findings of the AERC volume provide a powerful challenge to this story. First, they offer some support to the old challenge: that it takes ‘two to tango’. Or as Mobutu Sese Seko is quoted: “It takes two to corrupt – the corrupter and the corrupted” (p.406, citing Bob Geldof). In this view, African elites may be culpable but so too are their ‘partners’.

More importantly, the findings support a new challenge: What if most of the blame lies elsewhere? While governments have tended to pursue the policies shown to be ineffective in reducing capital flight, many of the real levers of power have lain outside the continent. In each of the following cases, for example, who is the corrupter and who the corrupted?

- An anonymous BVI company is awarded a cheap Zambian mining concession, then flips it to a UK-listed plc

- A Swiss bank holds a Nigerian resident’s overseas assets through a Jersey trust; nothing is reported to the Nigerian authorities

- A US-headquartered multinational shifts profit from Ghana to Luxembourg

We could go on; and indeed the book offers many examples. We should also consider other examples, such as that of a South African multinational shifting Uganda profits to Mauritius. We might perhaps settle on a view that the blame is very well shared indeed around the world. We might also wonder if poverty is not associated with corruption, so much as with exploitation by the corrupt.

At a minimum, the evidence presented by the AERC authors should serve to unstick the casual elision of corruption and poverty, and of capital flight and African policies.

As Nkurunziza (chapter 2) shows, the potential gains in poverty reduction from reversing capital flight are substantial.

Policy opportunities

The Sustainable Development Goals’ target to reduce illicit financial flows is a golden opportunity to catalyse improved quantitative methodologies; to ensure more and better data is available; and to introduce indicators that drive accountability for progress. But the SDGs will not fill the policy gap.

Although the ‘crazy ideas’ generated by civil society in the early 2000s now dominate the global policy agenda, there is a failure across the board – most obviously in terms of country-by-country reporting, and automatic exchange of tax information – to ensure that the benefits flow to developing countries as well as OECD members.

It seems that political power, rather than genuine commitment to transparency principles, still determines who is able to benefit. The Mbeki panel has called for greater progress in these areas. But is there an opportunity to sidestep, or indeed to leapfrog, much of the current issues by taking a more direct approach?

The final chapters of this important volume (15; and 16 – Boyce & Ndikumana in particular) detail a wide range of policy responses to the various findings, from capital controls and debt audits to some of the fundamental challenges to financial secrecy that the Tax Justice Network exists to champion – not least, fully public country-by-country reporting for multinational companies.

A global compact on financial transparency

The most striking proposal, however, is one not currently on the international policy agenda: a global compact among governments, CSOs and international institutions, covering strategies at the national, continental and global levels. Boyce & Ndikumana highlight the importance of:

- National governments integrating the various mechanisms and agencies that are relevant for each type of illicit flow;

- Continental conventions to provide a framework for harmonisation and coordination of national initiatives;

- Global civil society networks working more closely with local civil society organisations, with greater speed of communication, greater coordination and institutionalised collaboration.; and

- Global initiatives that have ‘adequate enforcement capacity. At the moment, global conventions do not have the legal capacity to hold individual governments accountable for the implementation of relevant dispositions; their rules are not binding at the national level’ (p.413)

The proposal, and the last point above all, carries an echo of an earlier proposal for an international financial transparency convention. In 2009, the Norwegian Government Commission on Capital Flight from Poor Countries (section 9.2.3) proposed such a convention, which would apply to all countries and include two main elements relating to transparency:

First, it must bind states not to introduce legal structures that, together with more specifically defined instruments, are particularly likely to undermine the rule of law in other states. Second, states which suffer loss and damage from such structures must have the right and duty to adopt effective countermeasures which will prevent structures in tax havens from causing loss and damage to public and private interests both within and outside of their own jurisdiction.

The commonalities with the proposed global compact are the recognition that states have responsibilities towards each other in respect of financial transparency; and that these are sufficiently serious, and their abnegation sufficiently damaging for other states and citizens, that practical enforcement is necessary.

The authors and others in the AERC network are now working on a range of country studies which will provide detailed further evidence of the issues in question. Meanwhile the ‘Stop the Bleeding‘ consortium that brings together a wide range of African actors to carry forward the agenda of the Mbeki panel is increasingly active.

Part of the reason this book is a milestone is that it sheds new light on what is known about the causes of illicit capital flows; offering supporting to the narrative that corruption and IFF should be seen not as the result of poverty, but rather as its exploitation – often led by external actors and always facilitated by financial secrecy elsewhere.

It will take on a new significance altogether if it also marks the starting point for an African-led process, perhaps backed by Norway and others, to develop an international agreement establishing the basic transparency expected – nay, required – from states toward one another; and making enforceable for the first time, claims against states for the damage caused by their financial secrecy.

[Talking of counter-measures – look out for a new TJN proposal launching tomorrow…]