This is a joint post with Andy Sumner and Luke Schlogl.

Global income inequality guru Branko Milanovic has confessed that he is “still not excited by the Palma“.

Since Branko is not only ace but also one of the few people that you might actually expect to get excited by an income inequality measure, it seems worth trying to address this sorry state of affairs.

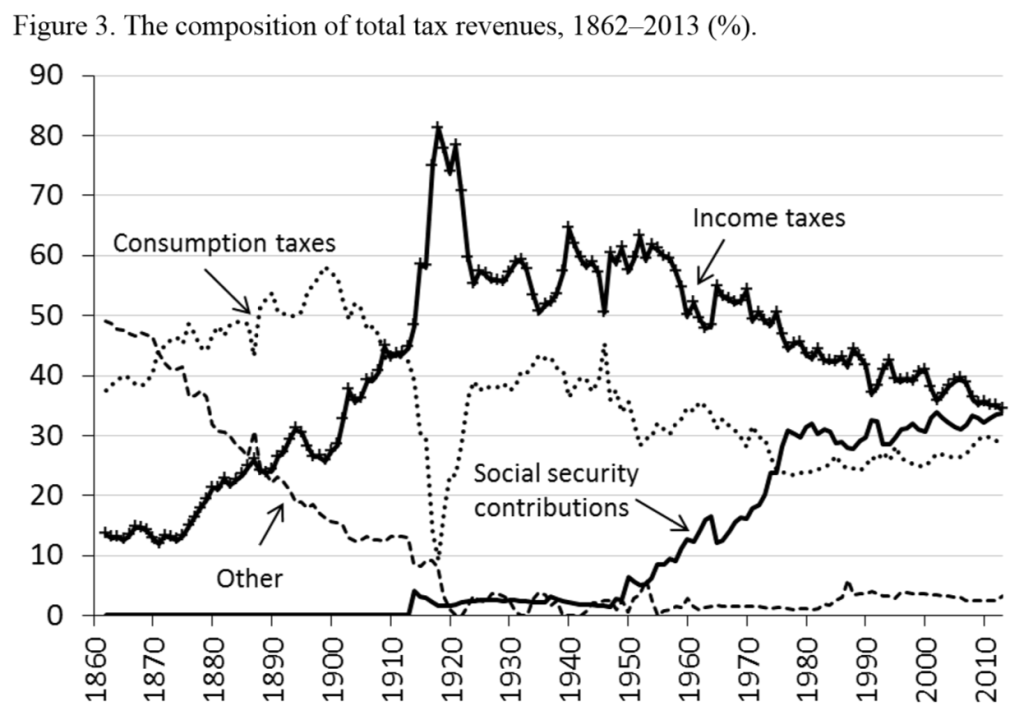

The Palma, proposed by Cobham and Sumner, is the ratio of the income share of the top 10%, to the income share of the bottom 40%. The reason for choosing this particular ratio, and for the name, is Gabriel Palma’s finding that those in the middle (deciles 5-9) capture approximately 50% of national income share, even in countries at quite different per capita income levels.

Branko’s post draws on a paper by Alice Krozer which argues that the stable middle of the distribution is actually a little larger, and so the ratio of the top 5% to the bottom 40% (Palma v.2) should be used instead.

Branko’s main point is this:

Palma’s logic is, as we have seen, to find parts of the distribution that, in terms of their shares, do not change regardless of the changes elsewhere, and to build a measure of inequality around these immovable parts. But these immobile chunks are no more immobile than Pareto’s top shares were. What is immobile may change between the countries, or across time. We see this it in Krozer’s own paper: there is no superior argument to assume that only the “central five deciles” are constant than to assume that “the central 55 percentiles” are constant.

With Palma we are thus building a general measure of inequality on the quicksand of what seems today more or less an empirical regularity. (Note that even when the regularity holds the five central deciles do not take exactly 50% of total income, but approximately 50%.)

But if the distribution changes and the middle loses while the bottom gains, and it turns out, for examples, that the deciles’ 4-7 shares are suddenly fixed, should we change our measure of inequality to look at the ratio between the top three deciles and the bottom three? Or if growth of incomes is concentrated in the top 1% or the top 5%, should be again redefine the Palma formula as Krozer has done? An infinite number of such permutations is possible, and an endless dispute will open up regarding what deciles’ shares are fixed and what not. The virtue of Krozer’s paper, despite what I think was her original intention, is to highlight the fragility of the empirical nature of the index and thus its basic arbitrariness.

Branko also reiterates two points that we have highlighted in respect of the typical technical axioms for inequality measures, which is that the Palma is insensitive to transfers within any of the three ‘chunks’ (the top 10%, middle 50% or bottom 40%).

Finally, he adds that “its decomposition properties—what is the Palma of two distributions whose Palmas and mean incomes are known—cannot, I think, be determined in general.”

We discuss these points in a little detail, including as they apply to other measures, in the CGD working paper introducing the Palma. So let’s focus here on the main charge: that the Palma relies on an empirical regularity which may change.

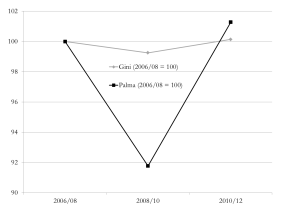

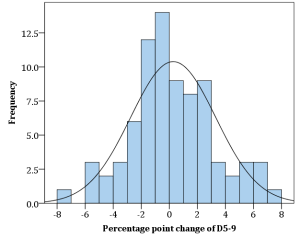

And… it’s true. The reason we choose this particular ratio is indeed because of the regularity that Gabriel Palma identified, and which further research has shown to hold over the range of available national income distribution data. Here, for example, is a histogram showing percentage point changes in the national income share of deciles 5-9. It’s centred closely around zero (ok, the median is slightly negative at -0.23).

And… it’s true. The reason we choose this particular ratio is indeed because of the regularity that Gabriel Palma identified, and which further research has shown to hold over the range of available national income distribution data. Here, for example, is a histogram showing percentage point changes in the national income share of deciles 5-9. It’s centred closely around zero (ok, the median is slightly negative at -0.23).

But as anyone who enjoyed Scotland’s football team qualifying for five consecutive World Cups from 1974 can testify, past performance is no guide to the future.

[Press play for consolation.]

So the Palma might be the right measure for today; but what if the empirical regularity were to cease to hold in the future?

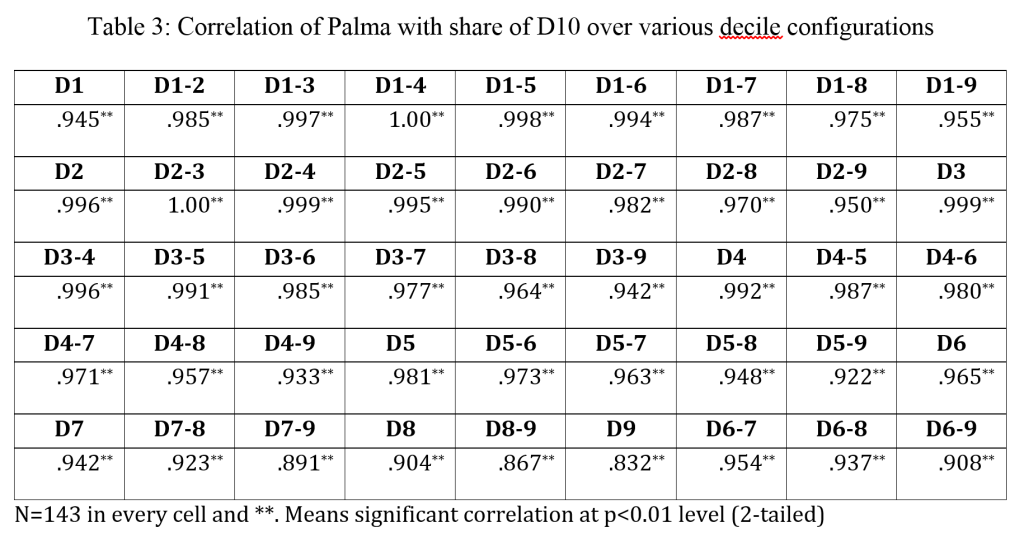

Gabriel’s main argument, of course, is about the driver of inequality: It’s the share of the rich, dude. And the data back this up too, as the correlations between the Palma and ratios of the top decile to other bits of the distribution confirm.

But let’s say that the future does hold a sufficiently dramatic change in the relative stability of the deciles 5-9. What would we be left with?

The Palma as a measure of income inequality, which:

- remains meaningful;

- pays insufficient attention to a part of the distribution that we may care about; and

- is explicit about doing so.

Just for fun, let’s consider the Gini on the same basis. The Gini is by construction oversensitive to the middle, and less sensitive to the tails. As such, it is an inequality measure which:

- remains meaningful;

- pays insufficient attention to a part of the distribution that we do care about; and

- is not explicit about doing so.

Note that this is true today, not in some imagined future. In fact, we would suggest that most people using the Gini do not realise that it is less sensitive to the tails; nor that it becomes increasingly less sensitive at higher levels of inequality.

As such, use of the Gini can hide the true extent of inequality – inadvertently or otherwise.

But we are guilty here of what Scottish football fans refer to as whataboutery: the defence of one (possibly bad) thing, by reference to a different (definitely bad) thing.

Instead, we should recognise there are weaknesses to any single measure of inequality. As Tony Atkinson, the grandfather of all modern economic analysis of inequality wrote in 1970, all measures reflect a subjective view – the difference is whether this is made explicit. And the class of measures Atkinson himself proposed in response are a technically outstanding response to the problem, only limited by their complexity from easy use for more popular communications.

The solution, such as it is, is to avoid the tyranny of single measures and to insist instead upon a breadth of measures. As Mike Isaacson put it in responding to Branko’s post:

My major point of contention with Milanovic here is not so much on the superiority of one index over the other, but rather the implication that we should invest ourselves in finding a superior index for inequality. Indices, merely by virtue of distilling the data from an entire economy down to one number, are inherently going to be problematic in terms of universal application. The choice of index (or indices if you’re into that whole “robustness” thing) should be guided by the data you have and the questions you intend to answer.

While the Palma versus Gini comparison may well favour the Palma, ultimately that’s the wrong question to address. We should ask ‘how best to measure’ (in a given context), not which (single) measure to use.

The Palma is exciting, if that’s your sort of thing, because it sheds light on the major aspect of inequality that the Gini quietly conceals – but not because there should be a tyranny of the Palma to replace the tyranny of the Gini.

And if that’s not exciting enough, here’s a Scottish defender opening the scoring against Brazil with a toepoke screamer from 20 yards. Wha’s like us?