Cobham, A. 2016. Breaking the vicious circles of illicit financial flows, conflict and insecurity. GREAT Insights Magazine, Volume 5, Issue 1. February 2016. Republished with permission of the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM).

Illicit financial flows (IFF) not only thrive on conflict and insecurity but exacerbate both, by undermining the financial and political prospects for effective states to deliver and support development progress. Policies to meet the Sustainable Development Goals’ target of curtailing IFF will also promote peace and security.

In 2014, the Tana High-Level Forum on Security in Africa took as its theme the impact on peace and security of illicit financial flows (IFF). Leading figures from across the region, including a range of current and former heads of state, discussed the nature and scale of illicit flows and the policy options available.

The subsequent report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, chaired by Thabo Mbeki, cited the Tana Forum background study (Cobham, 2014) and reiterated its analysis of the linkages with security; and so it was no surprise that the IFF target in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) appeared under Goal 16: ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’:

16.4 By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime…

The linkages between IFF and insecurity are not necessarily well understood, however. Assessing how the two issues interact can help to identify the range of policy responses that will support powerful progress.

Illicit financial flows

There is no single, agreed definition of IFF. The Oxford dictionary definition of ‘illicit’ is: “forbidden by law, rules or custom.” The first three words alone would define ‘illegal’, and this highlights an important feature of any definition: illicit financial flows are not necessarily illegal. Flows forbidden by “rules or custom” may encompass those which are socially and/or morally unacceptable, and not necessarily legally so. Multinational tax avoidance (as opposed to illegal tax evasion) might come under this category.

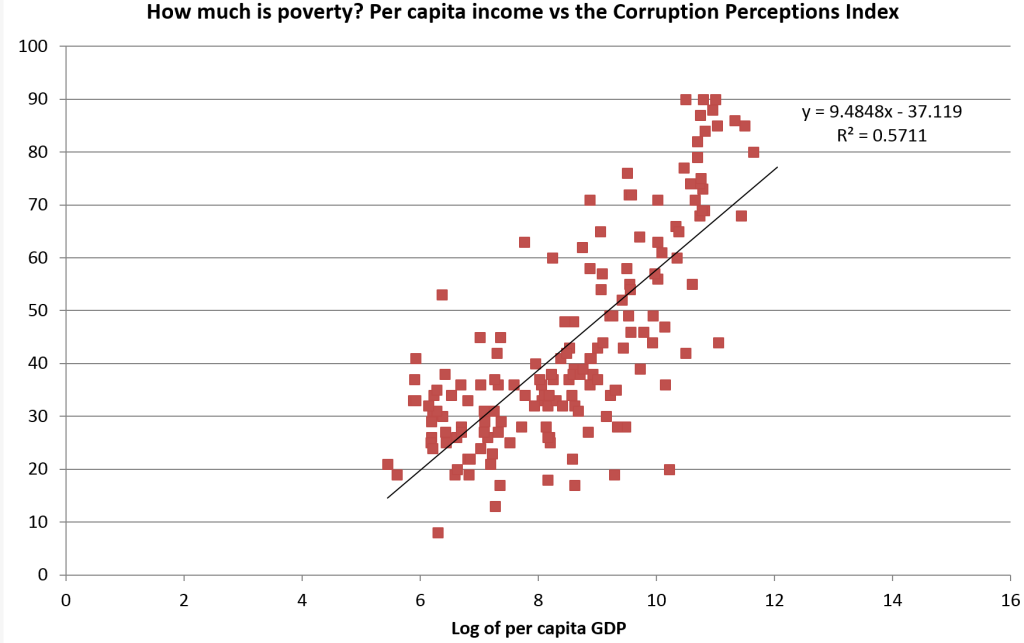

This particular example also shows why a legalistic approach may introduce an unhelpful bias. Commercial tax evasion affecting a low-income country where the tax and authorities have limited administrative capacity is much less likely either to be uncovered or successfully challenged in a court of law, than would be the same exact behaviour in a high-income country with the same laws but with relatively empowered authorities. A strictly legal definition of IFF is therefore likely to result in systematically – and wrongly – understating the scale of the problem in lower-income, lower-capacity states. For this reason above all, a narrow, legalistic definition of IFF should be rejected.

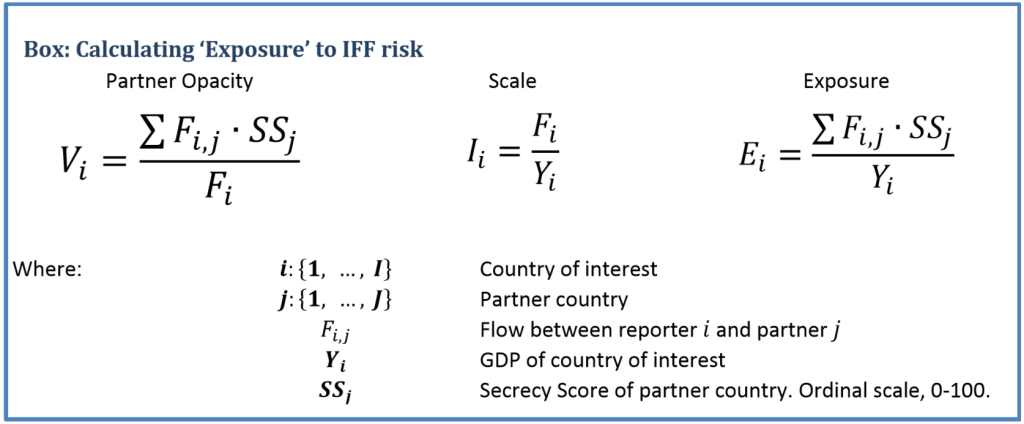

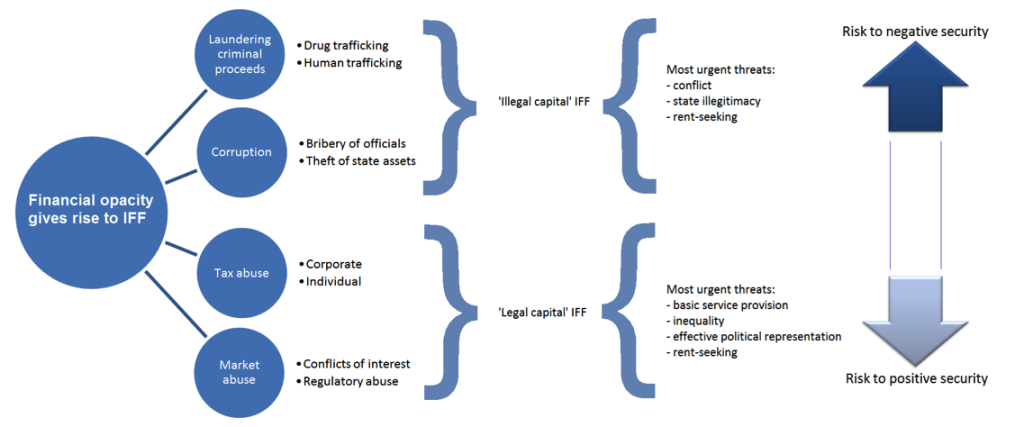

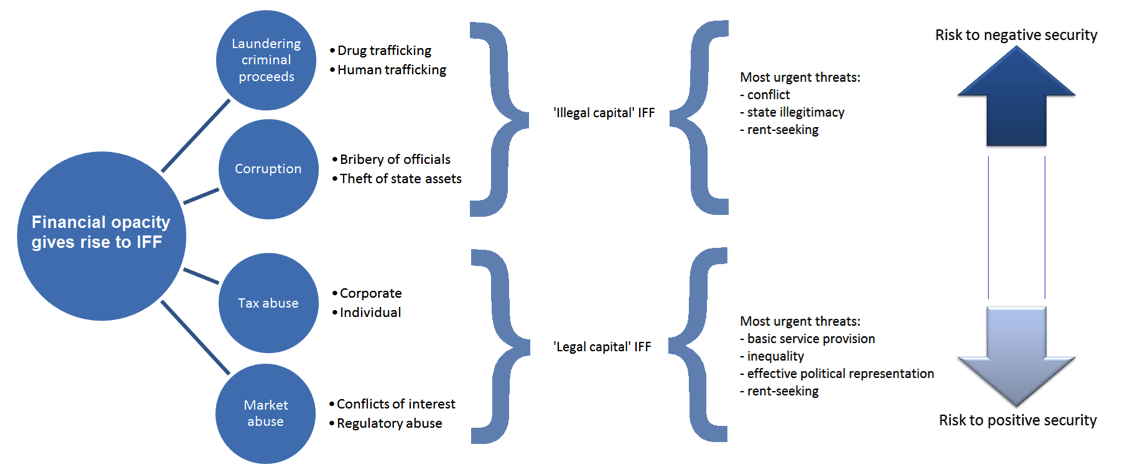

Figure 1: Main IFF types by nature of capital and transaction

The central feature of IFF – and incidentally a major reason their measurement is so difficult – is that they are deliberately hidden: financial secrecy is key, in order to obscure either the illicit origin of capital or the illicit nature of transactions undertaken (or both). As illustrated in Figure 1, four main types of behaviour are captured: 1) market/regulatory abuse (e.g. using anonymous companies to conceal political conflicts of interest, or breaches of antitrust law); 2) tax abuse; 3) abuse of power, including the theft of state funds and assets; and 4) laundering of the proceeds of crime. Figure 1 also highlights that there is a broader distinction between ‘legal capital IFF’ (tax abuse and market abuse, types 1 and 2) and ‘illegal capital IFF’ (the abuse of power and laundering of criminal proceeds, types 3 and 4).

Security and state ‘fragility’

There is growing agreement that the concept of fragile states – as a binary division against all other, ‘non-fragile’ states – is an unhelpful one for analysis. Instead, it is more useful to think of all states as occupying some position on a spectrum of (risk of) fragility. As the High Level Panel on Fragile States (2014) put it:

Fragility comes about where [pressures such as those stemming from inequality and social exclusion, or from new resource rents and resource scarcity] become too great for countries to manage within the political and institutional process, creating a risk that conflict spills over into violence – whether interstate or civil war, ethnic or tribal conflict, widespread criminality or violence within the family. Countries that lack robust institutions, diversified economies and inclusive political systems are the most vulnerable. In the most acute cases, violence has the effect both of magnifying the underlying pressures and eroding the institutions needed to manage them, creating a fragility trap from which it is very difficult to escape.

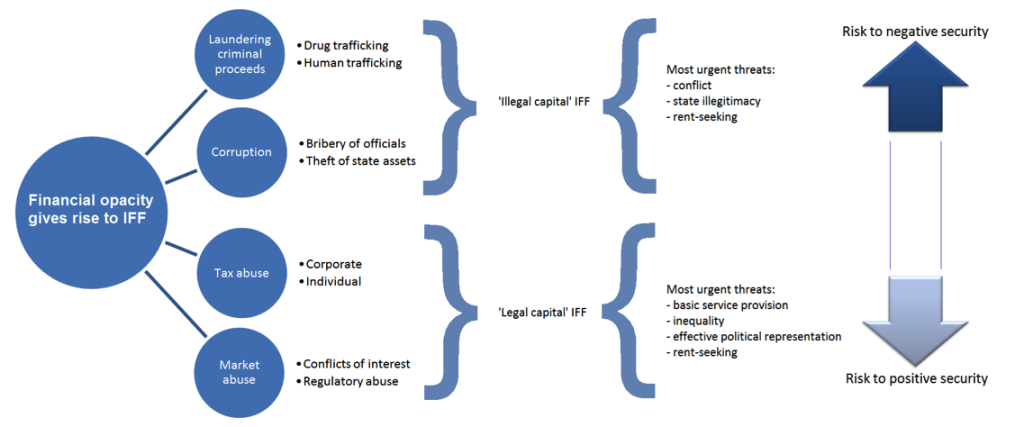

The risk of fragility is then closely related to a state’s ability to provide citizens with ‘negative’ security (to prevent personal, community, political and environmental insecurity) and with ‘positive’ security (to provide the conditions for economic, food and health security and progress). These two forms of security exhibit potentially mutually reinforcing relationships with particular types of IFF.

Two vicious circles

Figure 2 shows a vicious circle linking illegal capital IFF and problems of negative security. Where IFF derive from abuse of power – say, for example, the extreme behaviour of a kleptocratic leader – the cycle follows almost tautologically. The nature of the IFF itself undermines state legitimacy and both the capacity and interest to provide security, or indeed to act to curtail IFF.

When the rise in IFF reflects laundering of the proceeds of crime, it is the underlying crimes where the linkages are likely to emerge. Most dramatically, Cockayne (2011) finds that drug and human trafficking has led to little less than the criminalisation of governance itself in West Africa and the Sahel. He identifies two hubs that grew strongly after Caribbean counter-narcotics efforts in the 1990s pushed the trade elsewhere: one around Gambia, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, and the other around Benin, Ghana and Togo. In addition, Cockayne highlights important services provided in other states – namely money laundering in Senegal, and transit in Mali, Mauritania and Niger. The growing involvement of the state in criminal activity (including IFF), and the growing power of criminality over the state, make the vicious circle somewhat inevitable again.

Figure 2: The vicious cycle of negative security and illegal capital IFF

Much of the problems of conflict and negative security arise in countries characterised by low levels of institutionalisation of authority, a heavy reliance on patronage politics and an accordingly high level of allocation of state rents to unproductive activities (patronage, to maintain the political machine). For a rent-seeking patronage order to function, it must resist or evade the pressures to institutionalise state finance – through, for example, an incentive structure in which senior officials have a personal interest in financial opacity and the misuse of public funds, and fiscal policy is subordinated to the ‘political budget’ (the state allocation for patronage purposes). Major sources of funds such as natural resource companies may be rewarded through the opportunities to evade tax with impunity, and may maximise net profits through bribery.

In turn this kind of state structure creates structural incentives for violence. Kleptocracy will tend to require violence to protect the position of privilege; those outside may resort to force to extort rents from those in power, or to challenge for the prize of (illegitimate) power itself.

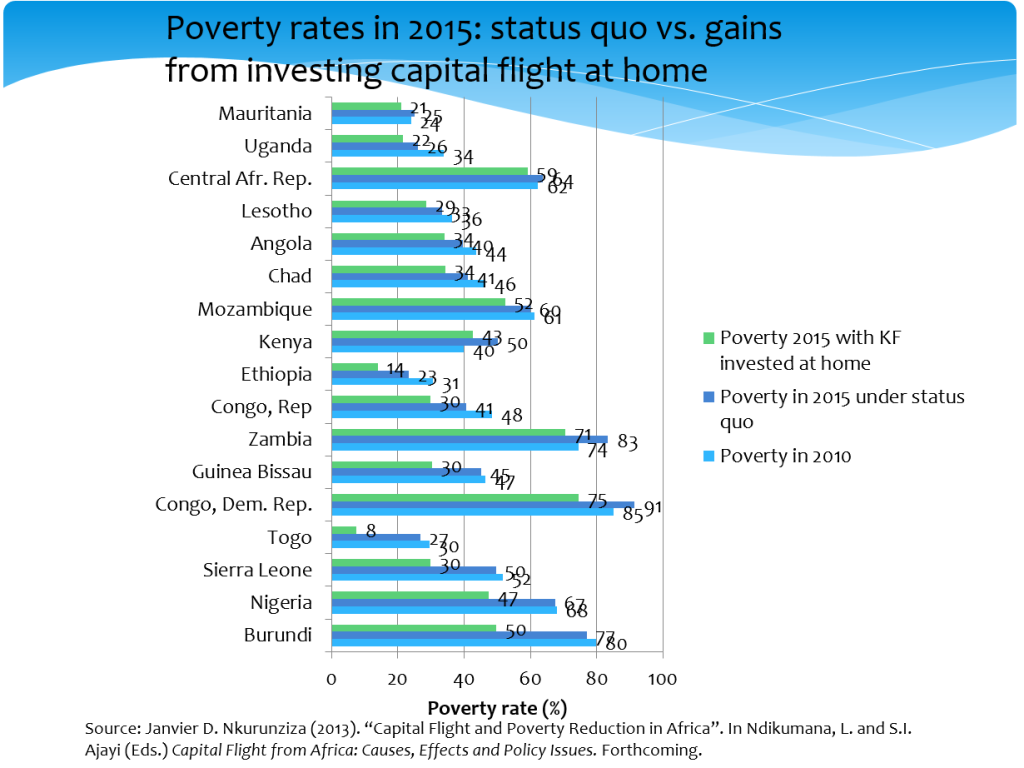

All four IFF types shown in Figure 1 are likely to result in reductions in both state funds and institutional strength – that is, they undermine governance as well as domestic resource mobilisation. While little research has sought to quantify the governance impact, and some attention has been given to the theft of state assets, a growing body of literature seeks to assess the financial scale of flows and the revenue losses associated with particular elements. Consistently, the scale of IFF and of revenue losses from corporate profit-shifting and from individual evasion through undeclared offshore assets is greater in lower-income countries; and often material in respect of countries’ GDP. Indicative estimates of the resulting impacts on basic human development outcomes such as child mortality suggest these too are powerful indeed – potentially bringing African achievement of the Millennium Development Goal target forward from an estimated 2029 to 2016, for example (O’Hare et al., 2014).

Figure 3: The vicious cycle of positive security and legal capital IFF

Figure 3 illustrates the vicious circle that can arise between these largely legal capital IFF, and problems of positive security. Bluntly, revenues are undermined where they are most needed; and further institutional damage follows from the weakening of the state-citizen relationship that is built on effective taxation.

IFF and security: Policy implications

At the Tana Forum in 2014, President Salva Kiir of South Sudan told how the ‘vultures’ had circled the new state even before it came into existence, building relationships with soldiers and others, so that when the moment came they were poised to create a web of contracts that channelled away oil revenues into anonymity – without delivering on the contracts:

When peace was signed, the vultures that were hovering over Sudan landed. We have learned in our cultures that when you see vultures hovering around, there must be a dead animal – or something is going to die… They knew there would be a vacuum of administration there… That [oil] money was disappearing day by day to where you cannot trace it.

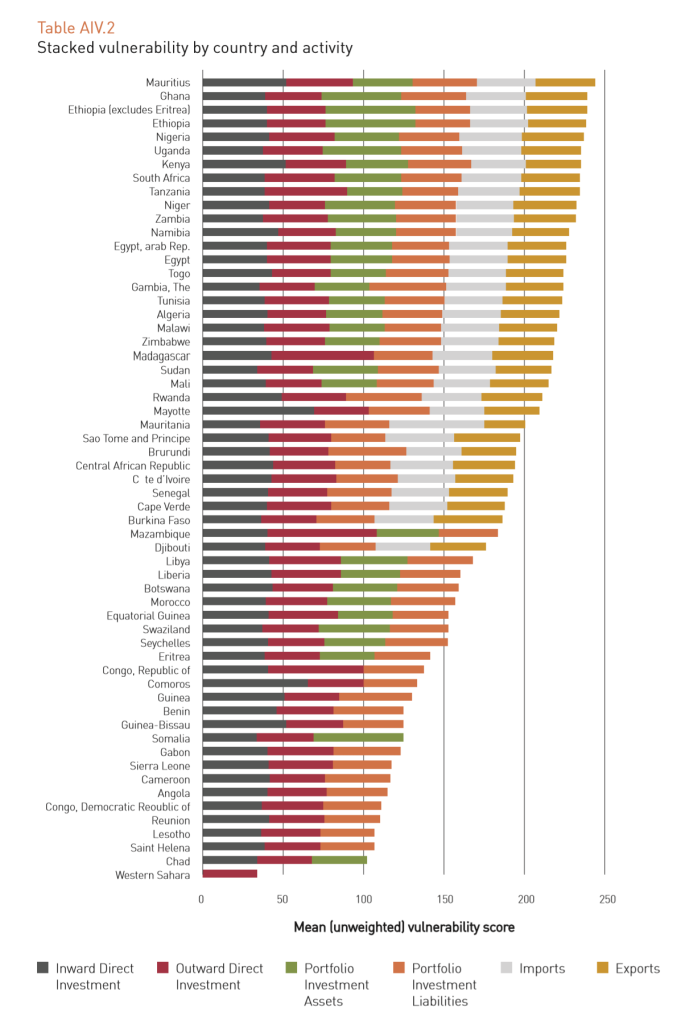

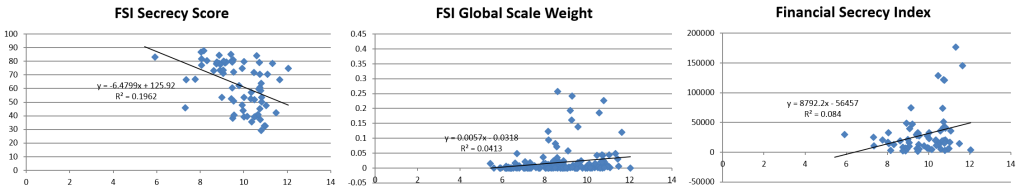

The central feature of IFF is that they are hidden, typically by the financial secrecy provided by other jurisdictions. The secrecy in question relates primarily to the provision of vehicles for anonymous ownership such as shell companies; to the refusal to provide information on foreigners’ assets and income streams to their countries of tax residence; and to the type of corporate opacity that obscures the worst excesses of multinationals’ profit-shifting. As shown by the Tax Justice Network ranking of tax havens, the Financial Secrecy Index, this includes many of the leading economies – not least the USA, ranked third.

States can protect themselves to a degree, by ensuring greater transparency of public contracts for example, and public country-by-country reporting by multinationals; and by engaging fully in the multilateral process for automatic exchange of tax information. But while other states insist on selling secrecy, major obstacles will remain.

Success in the Sustainable Development Goals target of curtailing illicit financial flows would contribute to reducing risks of state fragility across the board – and to achieving many human development targets too. But such progress depends on international progress against financial secrecy. A significant step would be the adoption of indicators for target 16.4 that will ensure individual states are held accountable for the secrecy they provide globally – and the IFF they stimulate as a result.

The following indicators (Cobham, 2015) draw from the agreed policy positions in the Sustainable Development Goals and the Financing for Development declaration from Addis, July 2015:

- For each country and jurisdiction, on what proportion of foreign-owned assets and to the states of what proportion of the world’s population, are they providing tax information bilaterally to others?

- For each country and jurisdiction, from which countries and jurisdictions are they receiving tax information bilaterally?

- For each country and jurisdiction receiving information, what proportion and volume of revealed assets were already declared by the taxpayer, and what resolution has reached each year in respect of the remainder?

- For each country and jurisdiction, for multinationals making up what proportion of the declared multinational tax base is country-by-country reporting publicly available?

The harder it is for vultures to hide, the fewer may be the unnecessary deaths suffered.

Figure 4: Overview of IFF and security linkages

References

Cobham, A., 2014, ‘The impact of illicit financial flows on peace and security in Africa’, Tana High-Level Forum on Security in Africa Discussion Paper.

Cobham, A., 2015, ‘Uncounted: Power, inequalities and the post-2015 data revolution’, Development 57:3/4, pp.320-337.

Cockayne, J., 2011, ‘Transnational threats: The criminalization of West Africa and the Sahel’, Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation Policy Brief (December).

High Level Panel on Fragile States, 2014, Ending Conflict & Building Peace in Africa: A call to action, African Development Bank: Tunis.

High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, 2015, final report.

O’Hare, B., I. Makuta, N. Bar-Zeev, L. Chiwaula & A. Cobham, 2014, ‘The effect of illicit financial flows on time to reach the fourth Millennium Development Goal in Sub-Saharan Africa: a quantitative analysis’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 107(4), pp.148-156.

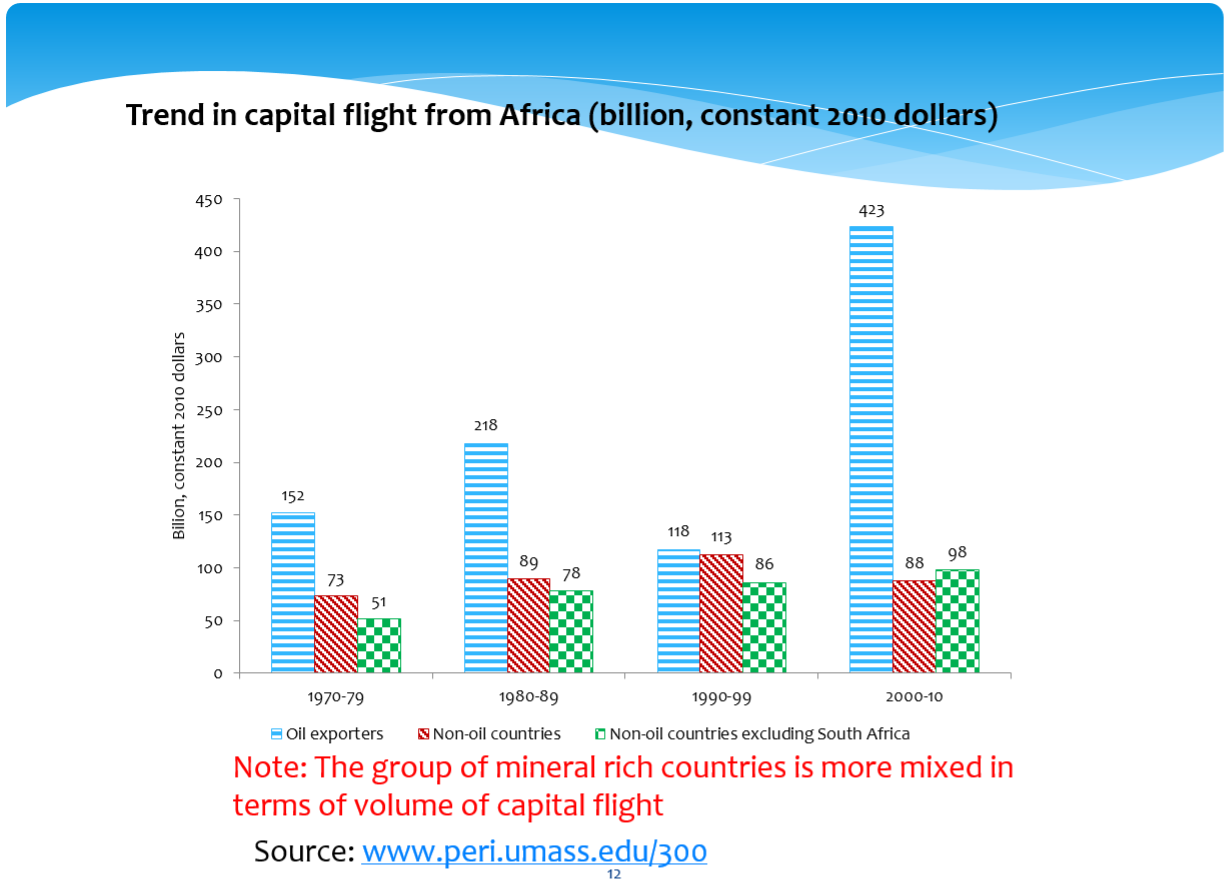

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015,

Ibi Ajayi & Léonce Ndikumana (eds.), 2015,  The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include:

The book’s major contributions lie in the analysis of the determinants, and as importantly the non-determinants, of capital flight. The non-determinants include: