Update: here’s an interview I did with Share Radio which goes through the key points.

Cross-posted from TJN.

On this quiet August day, the US Treasury has fired the first shots of a tax war with Europe. And while it’s wrapped up in a claim to defend international tax cooperation, it looks more like an attempt to prevent an effective measure against international tax-dodging – carried out, not least, by US companies. At the same time, the US continues as the leading hold-out against the automatic exchange of individuals’ financial information; and to resist the growing tide of public registers of the beneficial ownership of companies. The stage is set for a prolonged battle.

By publishing a white paper titled ‘THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION’S RECENT STATE AID INVESTIGATIONS OF TRANSFER PRICING RULINGS’ (h/t @RichardRubinDC), the US has signalled an end to a period of quiet tension. This long post considers why this matters; then sets out the main contents of the white paper; before concluding with an assessment of what is possible in the ensuing hostilities.

Implications

We explore the white paper’s main points below, but note first its significance. For one thing, it confirms just how bad relationships between the US and the Commission have become on the subject of corporate tax. The white paper is the opposite of gentle diplomacy – and quite close, in parts, to an outright threat.

Second, it confirms (once again) that the OECD BEPS process has failed. Failed to rescue international tax rules by somehow making the arm’s length principle into a coherent, working approach; and failed to defuse the tensions over tax abuses, even among its own member states. (Non-members had swiftly learned not to expect their views to be given much weight; for the members to see their own agreement fall apart so quickly is less expected.)

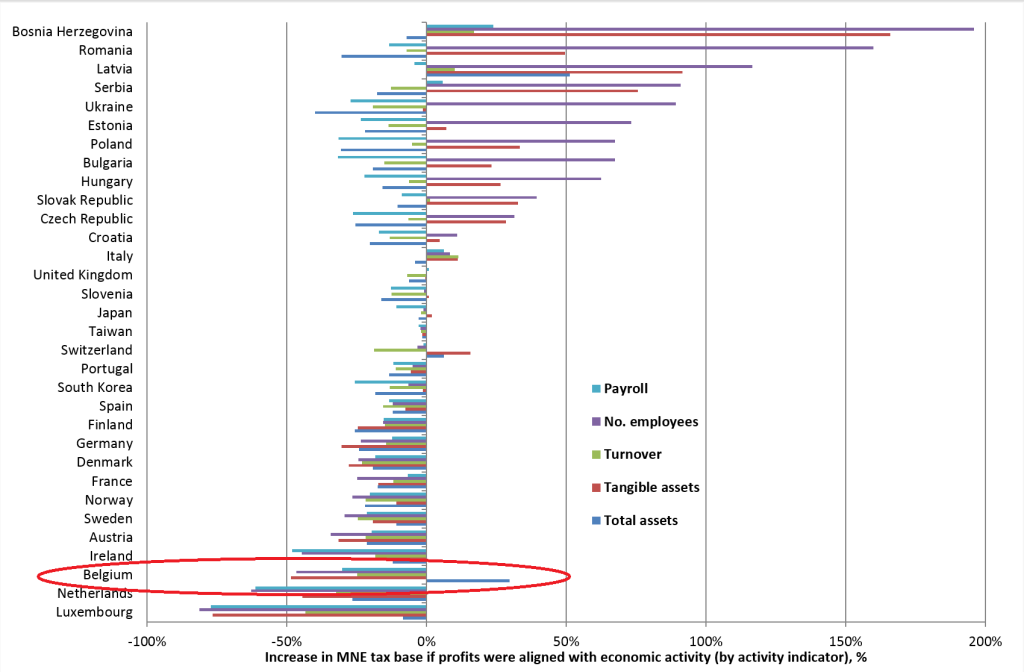

Prior to this publication, there had been two main views on the US Treasury’s approach to corporate tax abuses. One was that Treasury was so firmly in the pockets of the more aggressive multinationals that it had effectively led their lobbying against more progressive BEPS measures such as the publication of country-by-country reporting. The other view was that Treasury was walking a line, allowing others (like the Commission) to take the blame for being aggressive but happy to see a real reduction in the misalignment of profits relative to the location of real economic activity via a voluntary disclosure procedure, or indeed by other methods.

In that second view, the Treasury is fully aware of the evidence showing that by far the biggest loser from the tax-dodging of US-headquartered multinationals is… the US itself. In the first view, this knowledge is either overlooked or seen as of only secondary importance compared to the perceived value of ensuring a competitive advantage for these national champions. And it is the first view for which the white paper appears to offer support.

What is undoubtedly the case is that the unveiled threats in the white paper represent a major escalation in hostilities, triggered by frustration with the Commission’s continuing pursuit of the state aid cases.

Main points

The Treasury paper contains three main elements: a rationale for its own existence, a set of arguments against the Commission’s approach to state aid, and a bargaining position for an end to the conflict. We consider each in turn.

Rationale

Were the white paper not such an aggressive document, it would be almost curious to see such a justification laid out. But here it seems necessary. The argument made is that the ongoing cases have “considerable implications for the United States-both for the U.S. government and its companies”. A number of specific implications are discussed, including that the cases:

- Undermine the BEPS project;

- “[C]all into question the ability of Member States to honor their bilateral tax treaties with the United States”;

- May lead to tax repayments that ” effectively constitute a transfer of revenue to the EU from the U.S. government and its taxpayers”;

- May have “a chilling effect on U.S.-EU cross-border investment”; and

- Set “an unwelcome precedent for tax authorities around the world to take similar retroactive actions that could affect U.S. and EU companies alike.”

It is tempting to dismiss (1) by noting that BEPS has already been substantially undermined – first by the US-led refusal to countenance inclusion of unitary approaches, and second by the ‘competitive’ approaches of major members such as the UK in protecting their own favoured mechanisms to attract BEPS activity from elsewhere. But, the Treasury does have a point here: if the EU had wanted to curtail such activity as is being revealed in the state aid cases of Apple, Fiat, Starbucks and Amazon, why not ensure that BEPS did so? Unless the concern was only backward-looking?

On the other hand, the US was an important blocker in key areas of BEPS – not least, around corporate transparency. So it is unsurprising if the EU wishes to pursue at home some of the aims it could not achieve through the OECD.

Points (2), (4) and (5) constitute forms of threat. If the Commission pushes ahead with further cases, it risks seeing the US question member states’ bilateral tax treaties; discourage US companies from investing; and consider retaliatory, retrospective action against EU companies. Food for thought, certainly, for the Commission and member states.

The key point, in terms of ‘Implications for the United States’ (which is the section heading), is 3. In full, the white paper states:

There is the possibility that any repayments ordered by the Commission will be considered foreign income taxes that are creditable against U.S. taxes owed by the companies in the United States. If so, the companies’ U.S. tax liability would be reduced dollar for dollar by these recoveries when their offshore earnings are repatriated or treated as repatriated as part of possible U.S. tax reform. To the extent that such foreign taxes are imposed on income that should not have been attributable to the relevant Member State, that outcome is deeply troubling, as it would effectively constitute a transfer of revenue to the EU from the U.S. government and its taxpayers.

Aside from the multiple conditionality of this statement, it is hard not to see the Commission reflecting on this with considerable scepticism. First, because the US already tolerates a very high degree of tax-reducing behaviour by its own companies. If this was the real concern, why not address it directly – rather than seek to prevent any inadvertent collateral losses due to action elsewhere? Why not, for example, take steps to reduce the major misalignment that exists between the shares of global activity and global profit that US-headquartered multinationals currently attribute to their home jurisdiction? Or simply abrogate the deferral rules that have led to the creation of a two trillion dollar offshore cash pile?

Second, even if the repayments did give rise to reduced US tax payments, if the repayments are themselves correct (as the Commission would argue they will be), then any US losses would simply reflect a the rightful reallocation of taxing rights – as opposed to a snatch and grab raid. The culprits would be the previously unrecognised profit-shifters, rather than the Commission.

In reality, of course, the likelihood of significant tax implications for US coffers seems small – hence the conditional statements. In particular, the likelihood that companies arranged low-to-zero effective tax rates in Europe, in order to repatriate the proceeds and then pay tax at (difference to) the US rate, seems exceedingly low. Much more likely is that such funds were held offshore and never triggered a US liability.

If this is accurate, then the US interest rests either on its genuine concern over the fate of BEPS, and the general degree of international cooperation; or on the likely implications for US companies, facing not only an end to some lucrative profit-shifting arrangements, but also retrospective penalties. (Whether the US should consider such arrangements affecting European tax liabilities as being in its own enlightened national interest is, of course, another question entirely.)

Legal arguments

The legal arguments make up the bulk of the paper, in two sections. The first, no doubt entirely coincidentally, looks rather like the basis of a legal brief for companies that might wish to mount a challenge to the Commission. The argument is made, by case law, that:

- “[T]he Commission has collapsed the concepts of “advantage” and “selectivity,” which are distinct requirements under State aid law. In the State Aid Cases, the Commission simply examined whether the measures at stake conferred a “selective advantage” on the companies under investigation, rather than separately assessing the existence of an advantage and the selective character of the measure, as it had done in prior decisions”; and

- The new approach means that economic advantage for a multinational would be sufficient: “The Commission’s position that individual transfer pricing rulings are selective when given to a particular multinational company, even when other multinational companies could have obtained them, constitutes a new approach that has not previously been applied. “

The second section then makes the case that, if a new approach to state aid has indeed been applied, there can be no legal basis for retrospective action:

With no indication of the Commission’s new approach, U.S. companies have been receiving transfer pricing rulings from EU Member States for decades and had no reason to doubt their legality. Under these circumstances, recovery of past allegedly unpaid tax would be inconsistent with EU legal principles and the Commission should avoid retroactive enforcement.

Whether these arguments constitute a powerful shot across the Commission’s bows or not is hard to know at this point. We would not, of course, be surprised to hear echoes of these in individual companies’ appeals…

Negotiating stance

The white paper goes on to lay out further detail in support of the ‘rationale’ points discussed above, including the threat to BEPS and international consensus on transfer pricing. The conclusion is short and direct:

V. Conclusion

The U.S. Treasury Department continues to consider potential responses should the Commission continue its present course. A strongly preferred and mutually beneficial outcome would be a return to the system and practice of international tax cooperation that has long fostered cross-border investment between the United States and EU Member States. The U.S. Treasury Department remains ready and willing to continue to collaborate with the Commission on the important work of ensuring that the international tax system is fair, efficient, and predictable.

Shorter version: ‘Change course, or we will take action.’

Really short version: ‘Bang!’

The outlook

Where do things go from here, now that the US has tipped the growing tensions into outright tax war? Will the EmpireCommission strike back? They certainly have a few options…

Hold the line, or back down?

First, there is a question of how the Commission responds on the immediate issue here. Backing down would presumably mean accepting the outcome of the current cases, and deciding not to pursue a further raft – a possibility the white paper refers to several times, with obvious concern.

We assume that pushing ahead with further cases would indeed trigger the Treasury’s unknown, threatened responses. Through quiet soft power alone, the discouragement of US companies’ additional investment in some prominent EU member states is quite possible. Raising of issues over member states’ bilateral tax treaties would take the conflict to quite a new level.

In no scenario does it now seem likely that we will see further cooperation to salvage some of the potential gains from the BEPS process, at least not any time soon. That leaves the EU to push ahead with its own agenda – and raises the possibility of some interesting tax policy ‘spillovers’…

Spillovers

First, the EU position on whether or not to require public country-by-country reporting should be watched closely. To the extent that US lobbying was a factor preventing a straight decision to go ahead and require publication of the full OECD standard data, policymakers may feel either that the gloves are off, and go ahead; or that holding off on this might be the diplomatic move until tensions calm. Given the strength of feeling in the European Parliament, early movement should not be ruled out.

Two further areas are of interest. While there may be some sense that European countries have not done this right, given their acquiescence in BEPS, the boot is very much on the other foot in respect of beneficial ownership and the automatic exchange of financial information.

The US has long been a laggard on beneficial ownership transparency, as its states compete increasingly aggressively with each other to offer the kind of anonymous company formation services that lay behind the Panama Papers. (Here’s a great new Reuters report, by the way, on Delaware’s role in the effort to defeat the great efforts of former Senator Carl Levin – h/t Jo Marie Griesgraber.)

Might the Commission choose to take a more aggressive stance on this now? It’s a possibility, as member states begin to introduce their own public registers of company ownership. But perhaps it’s too early in that process to begin prodding others.

Where Europe has long held the lead, however, is in the area of automatic information exchange. Here the Savings Directive has required members to provide information automatically for more than a decade; although only with US embrace of the principle of automaticity through Obama’s FATCA laws, was the resistance of major secrecy jurisdiction like Switzerland defeated. From that moment, the creation of an international standard for automatic exchange was inevitable.

Less expected, however, was the US U-turn which led to them (currently) being set to provide information to almost no other state – despite demanding it from each and every one. Whether the US Treasury’s first shots in the tax war are enough to swing European opinion remains to be seen; but one of the main political reasons against developing a ‘tax haven’ blacklist based on the automatic exchange of information, was that it would have caught the United States. And TJN’s proposal for counter-measures – a withholding tax on US financial institutions, based on FATCA – is still in the drawer.

Whatever the eventual result, the US Treasury has taken a major step today. A step which identifies it much more closely with defending the ability of its own multinationals to go untaxed, than with the support for international agreement in which the claim is cloaked. The openly confrontational nature of the white paper is surprising, but reflects longstanding tensions as European countries have sought genuine progress.

The first shots of what may become a major tax war have been fired.

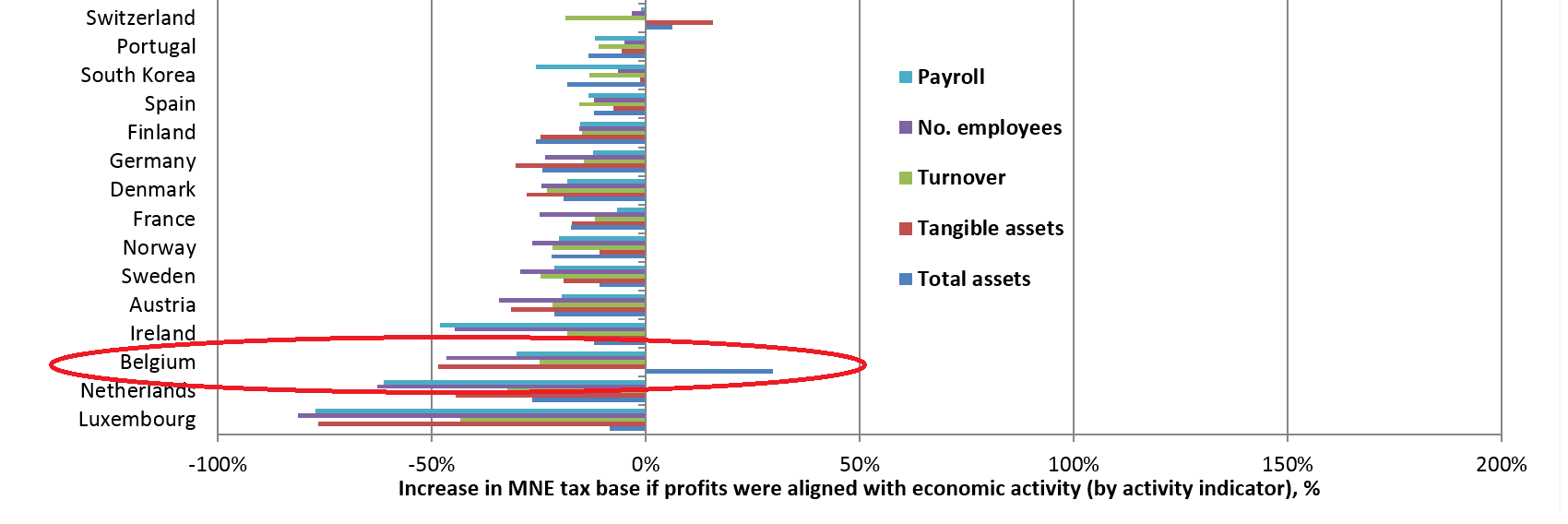

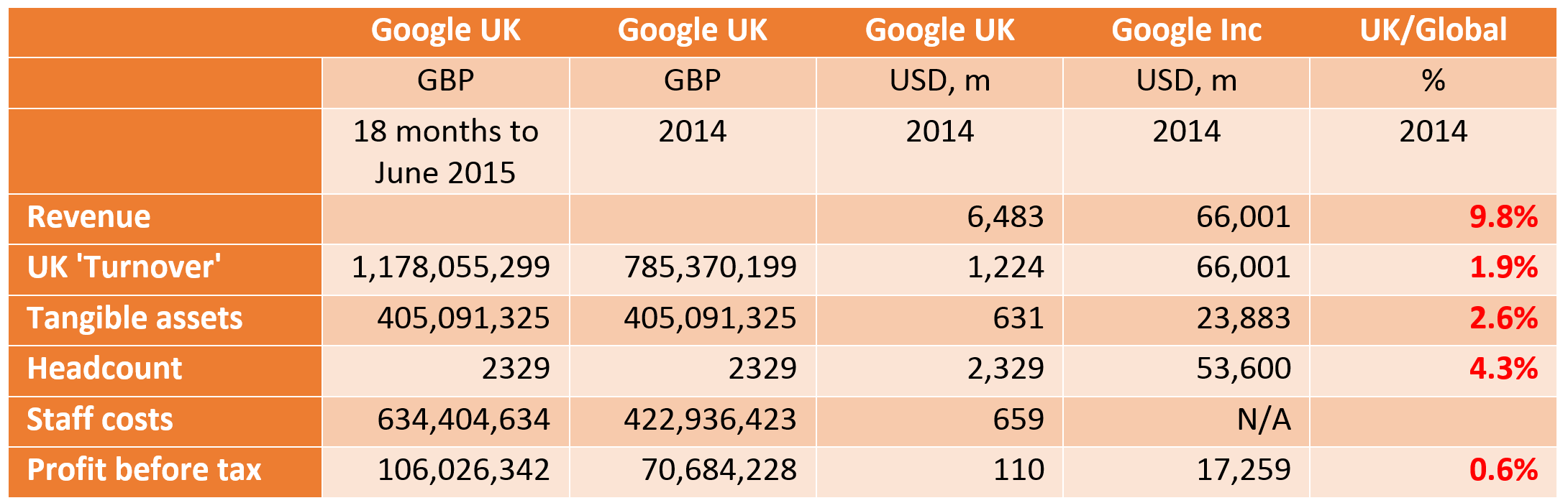

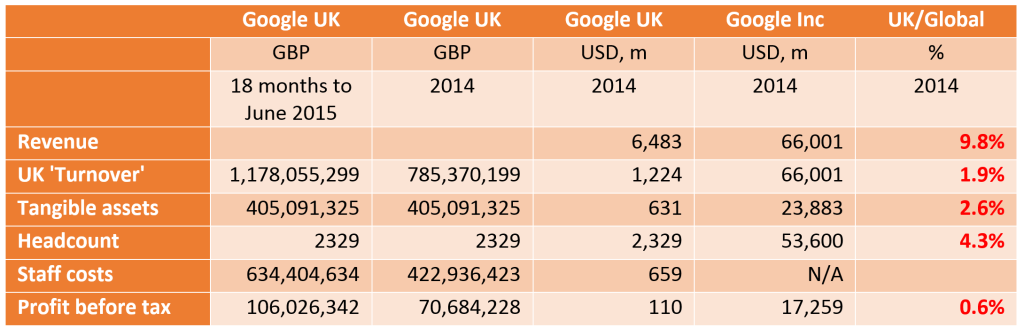

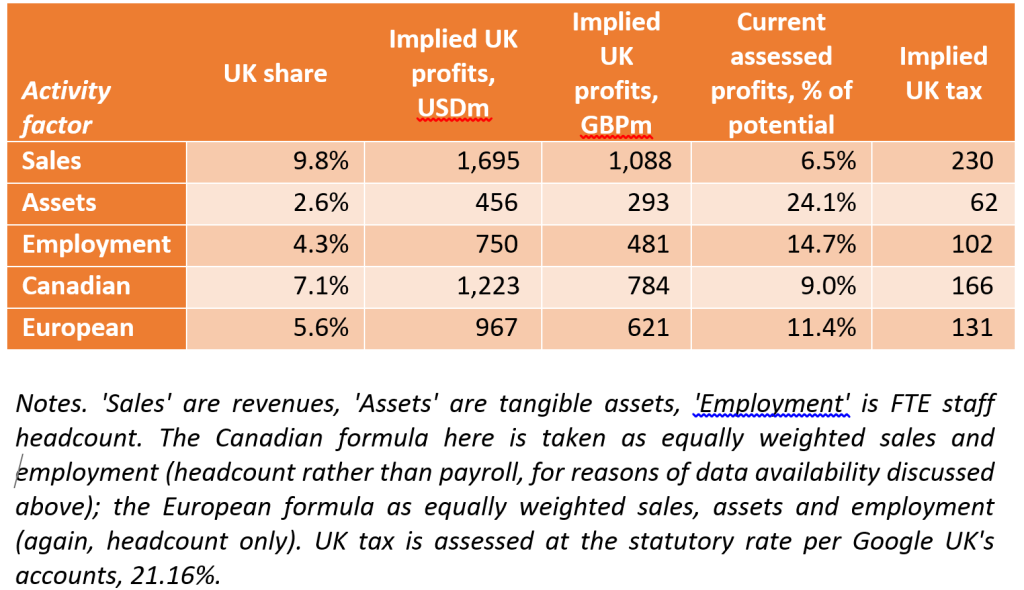

The Canadian and European multiple-factor formulae provide a broader base of economic activity against which to consider profit misalignment, and provide a closer range. The implied tax bill for 2014 is £131-£166 million; while current declared profits are 9-11% of the implied tax base.

The Canadian and European multiple-factor formulae provide a broader base of economic activity against which to consider profit misalignment, and provide a closer range. The implied tax bill for 2014 is £131-£166 million; while current declared profits are 9-11% of the implied tax base.

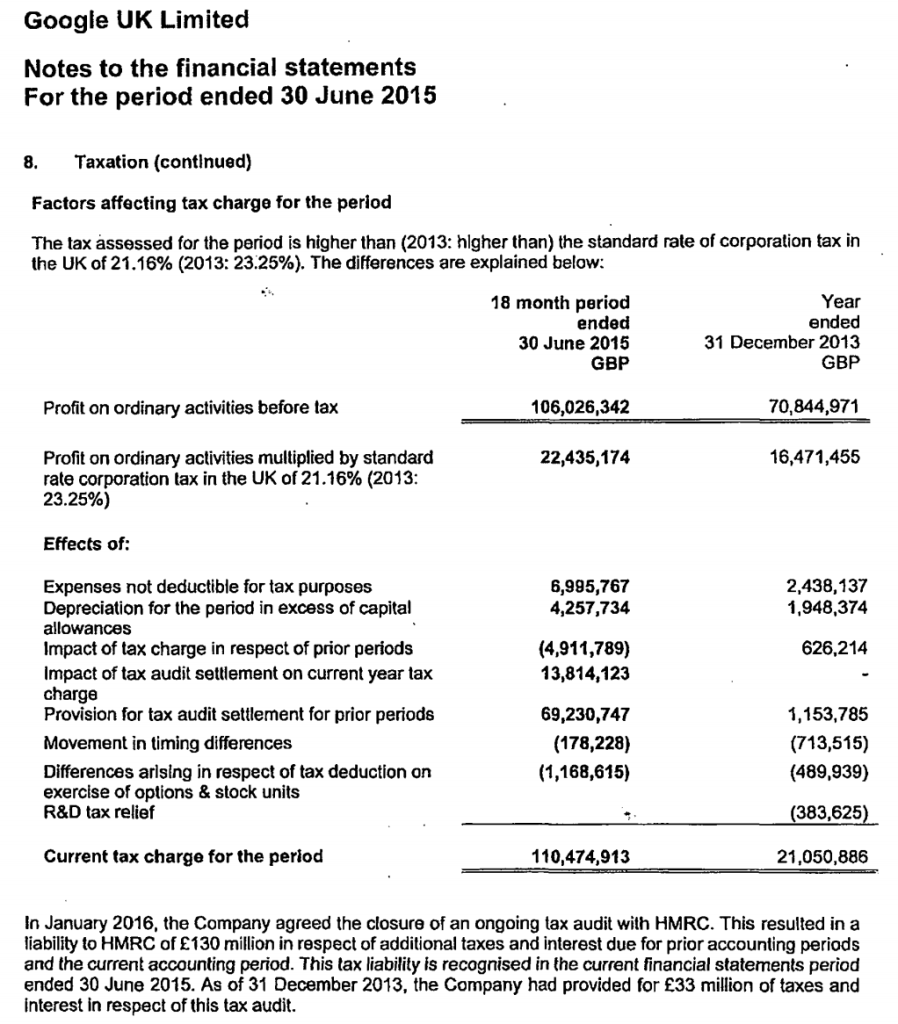

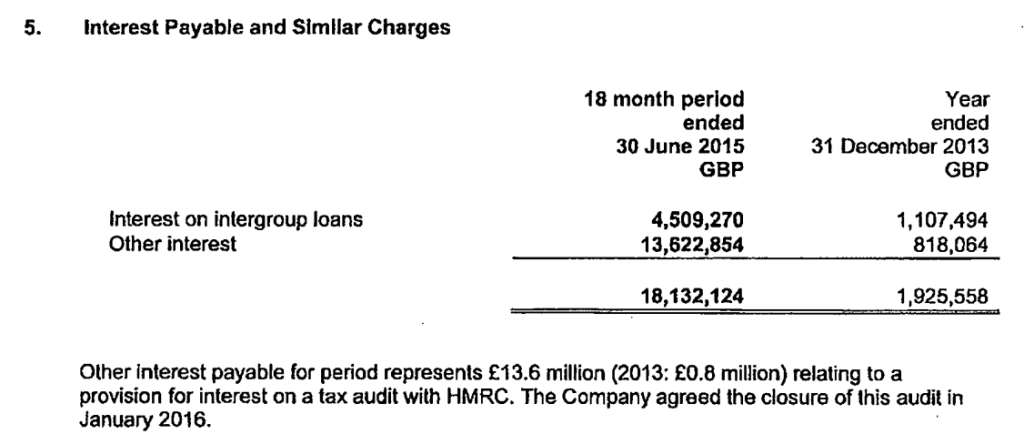

Finally, the newly released accounts (covering a year and half, after a change of accounting date) show a substantial increase in the provisions, and notes that £33m was the previous provision that now forms part of the overall £130m liability.

Finally, the newly released accounts (covering a year and half, after a change of accounting date) show a substantial increase in the provisions, and notes that £33m was the previous provision that now forms part of the overall £130m liability.