There’s been a good deal of coverage of the European Commission decision that Belgium’s ‘excess profit’ tax scheme is illegal, and so it must claw back unpaid tax from companies that were able to achieve double non-taxation on profits shifted into the jurisdiction. The focus has largely been on the implications for specific companies. It’s worth thinking more about different jurisdictions involved, and the possible risks facing the big 4 audit firms.

Basis of the EC tax ruling: Guaranteed double non-taxation

First, the ruling seems pretty clear cut, in principle at least, because the ‘excess profit’ approach is so transparently designed to engineer double non-taxation. Much like Ireland’s bad Apple agreement which accepted that the jurisdiction was not entitled to a share of profits that were shifted in but resulted from activity elsewhere, the Belgium scheme determined that any ‘excess profits’ would be exempt from tax.

The scheme defined excess profits as those bigger than an equivalent, purely domestic business would report – in other words, the result of a multinational’s activity elsewhere. Since these were by definition being reported in Belgium and not elsewhere, double non-taxation was the aim and indeed the guaranteed result. Bingo!

Whereas other cases (e.g. LuxLeaks) involved tailored responses to individual companies, the Belgium approach was consistent leading the Commission to conclude simply that:

We did not have to investigate the specific tax rulings to each company that are based on the scheme. They are automatically illegal.

Why Belgium? Who else?

As I said in various interviews, ‘België is niet de grote vis’ (Belgium is not the big fish), and the ruling is fascinating more because of the potential scale if a similar demand for clawbacks were applied to the bigger EU players in the profit-poaching business.

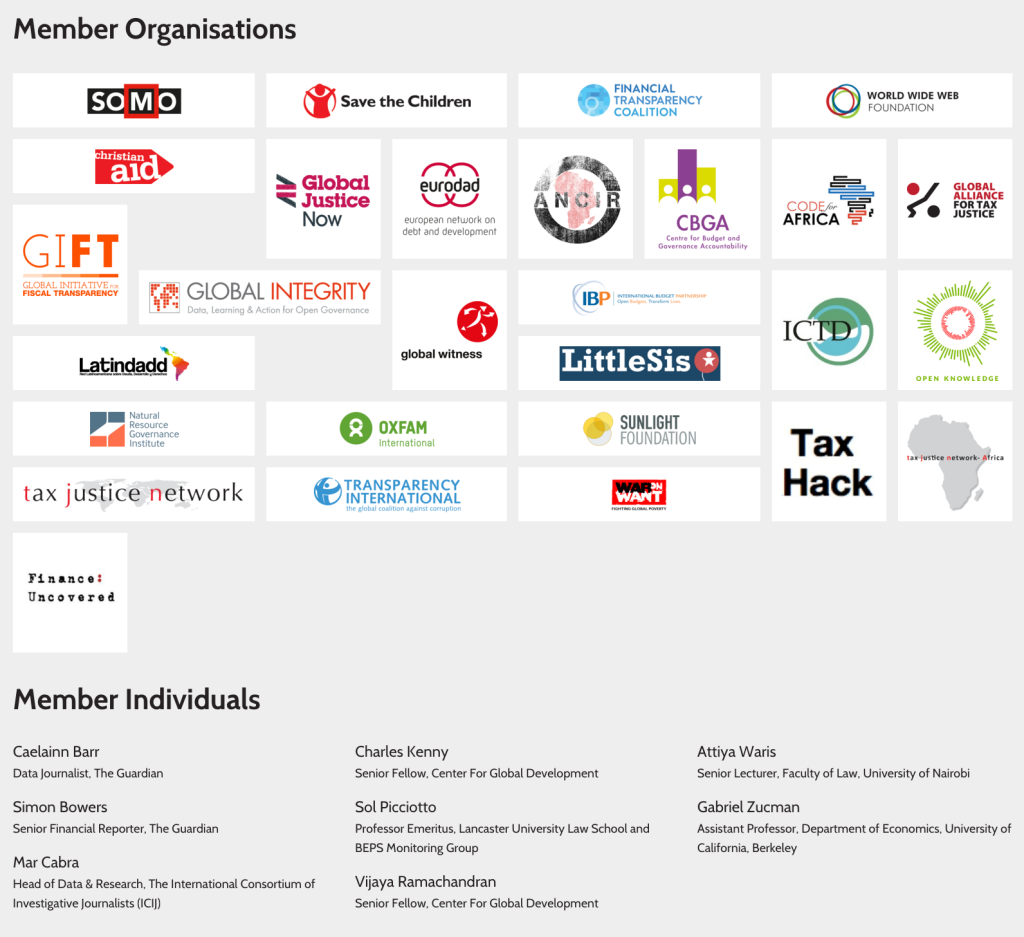

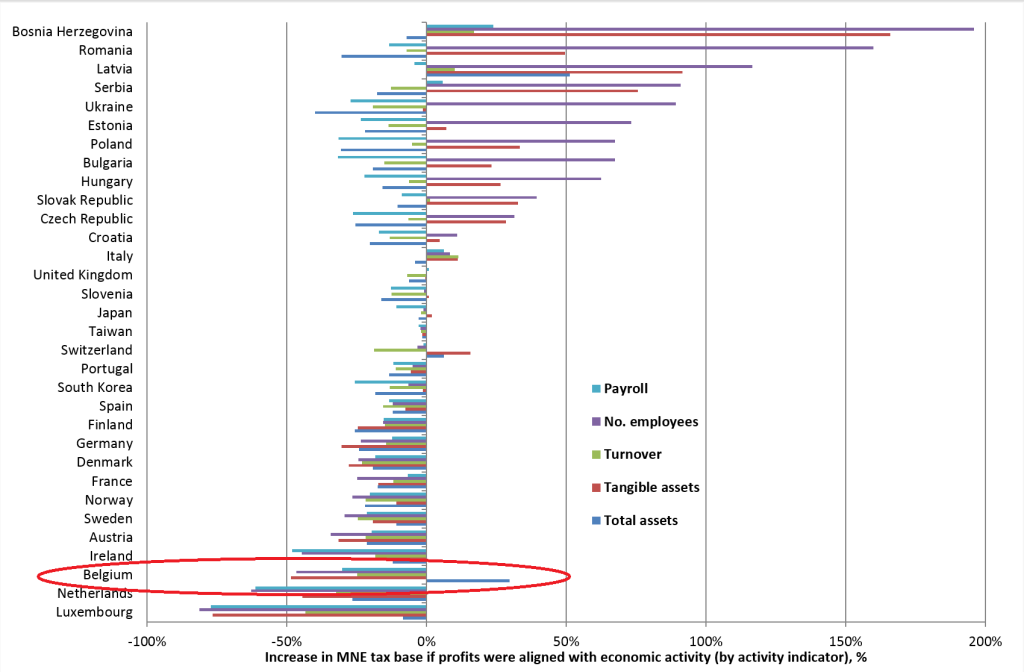

Our study of US multinationals, which we find to shift 25-30% of their global profits, shows that the majority of shifted profit goes through six jurisdictions: outside the EU Bermuda, Singapore and Switzerland; and inside, Ireland, Luxembourg and Netherlands. [New work from the US Joint Committee on Taxation, with access to firm-level rather than aggregate data, puts Cayman ahead of Singapore in the top six; ut the EU jurisdictions remain central.] Using global balance sheet data (predominantly capturing European multinationals), our earlier study confirmed the same three EU jurisdictions and also highlighted the roles of Belgium and Austria.

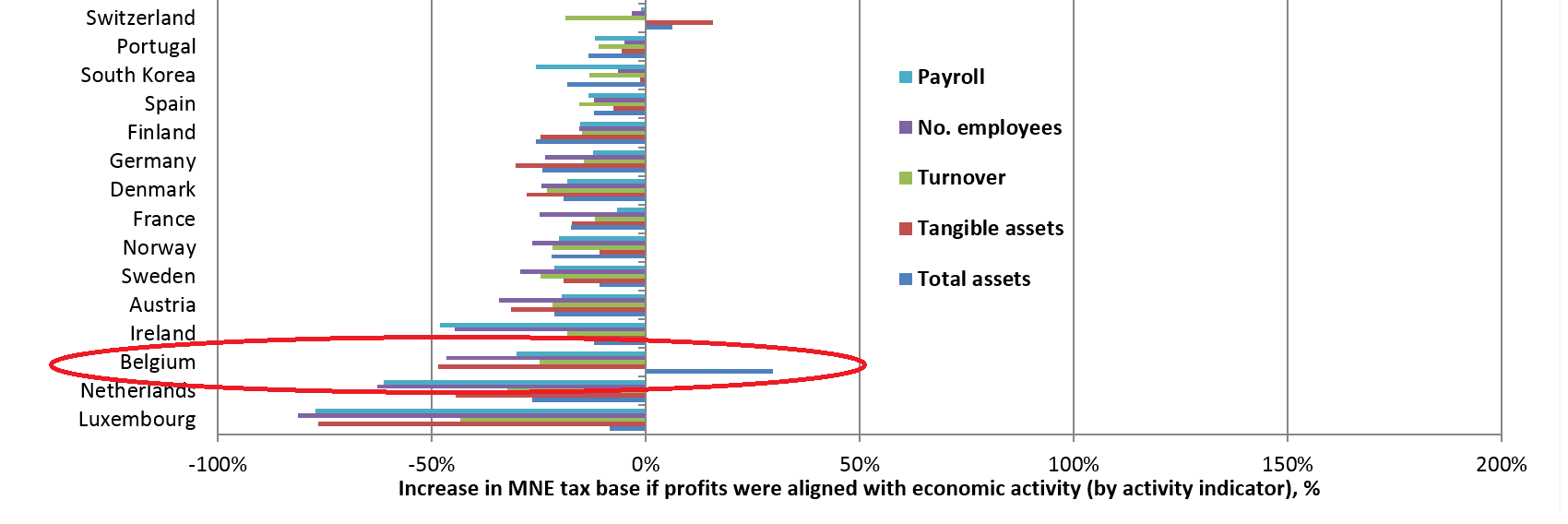

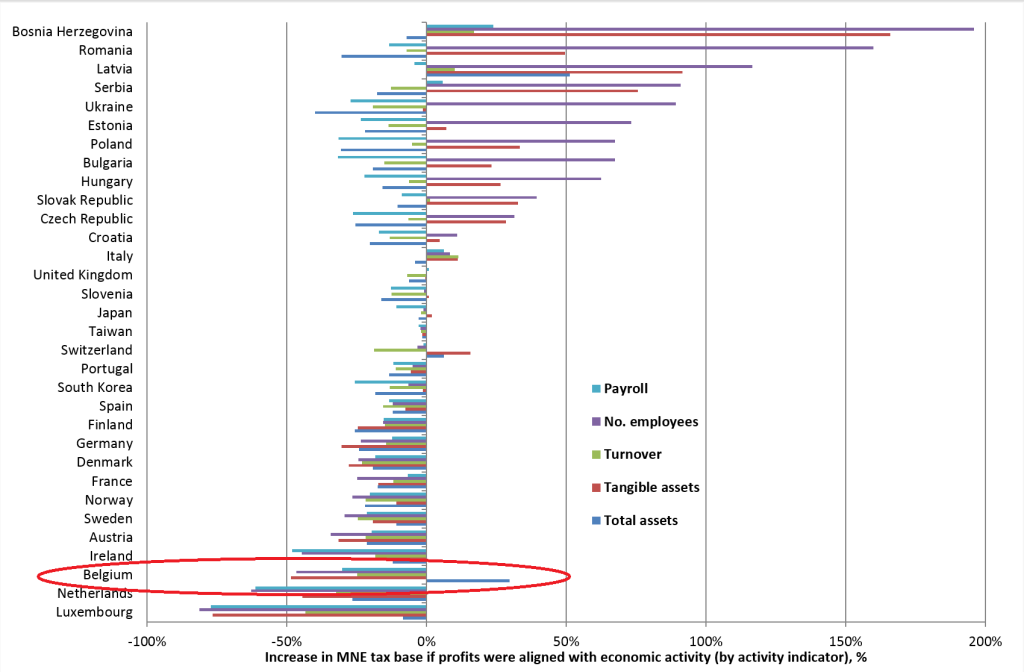

The figure, drawing from the results of Cobham & Loretz, 2014 using Orbis data, shows the share of declared profit which would be stripped away from each jurisdiction, if profits were to be aligned with each of the measures of multinationals’ economic activity (which was the declared aim of the OECD BEPS initiative). Belgium would stand to lose 25-50% of its declared profits under any measure of activity except intangible assets, a relatively extreme position.

Consistent with this view of Belgium as a location for profit-shifting by European multinationals in particular, the European Commission states that the clawback will amount to €700m, of which the bulk – around €500m – relates to European multinationals.

So while Belgium may not be such a grote vis internationally – it doesn’t register for US multinationals in the aggregate, for example – it’s certainly big enough for the European Commission to have bothered with.

But the really big money would be at stake if the same type of decision were to be taken with respect to the profit-shifting into Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Of these, the relative complexity of mechanisms in the Netherlands (using trusts and special purpose entities for example, rather than blunt rulings) may make it a harder target. But rulings in Ireland and Luxembourg are already in the Commission’s sights. If the doubly non-taxed profits here were required to be retrospectively taxed at applicable statutory rates, the effects would be substantial indeed.

Company calculations

What would that look like from the point of view of companies involved? Consider the Belgian case. Gross profit that might have faced an effective rate of 15-20%, say, in the countries where the underlying economic activity took place, was shifted into Belgium and declared as ‘excess’ and therefore not subject to tax – in any jurisdiction.

Applying the unmitigated Belgian statutory rate instead will have two main results. First, the overall tax paid will almost certainly (assuming interest is dealt with appropriately) be higher than if neither the scheme itself, nor any alternate profit-shifting arrangement, had been used. The Commission notes that for the Belgian companies used, 50-90% of profits were ruled as ‘excess’; so it’s unsurprising that companies like AB InBev are assessing their options.

The second effect is a more forward-looking one: the changes that the Commission decision may imply for current and future profit-shifting strategies. If the possibility exists for retrospective taxation on shifted profits, do companies become less aggressive? Or is there simply a premium put on the more complex and/or iron-clad methods – for example, will Netherlands structures become even more dominant? Will it favour the UK’s CFC and patent box mechanisms, now with the OECD BEPS mark of acceptability, over other (smaller) jurisdictions?

Big 4 risks

A further impact is that on the big 4 and other professional services firms that may have provided the advice on which basis multinationals made the particular profit-shifting decisions – and themselves profited substantially in doing so. If there is a case for companies to sue over bad advice in the Belgian case, imagine the exposure – for example – of PwC, if a substantial share of LuxLeaks cases were equivalently unwound? If so then at some point, given the vast scale of profit-shifting and the potential tax liability if statutory rates rather than 0-1% were to be applied, a question of financial viability could even arise.

Looking forward again, will multinationals approach such tax advice differently if the possibility of retrospective action remains? Does this simply reduce the value of the advice, or change the willingness to consider it?

And for the big 4 and their staff, with the nature – and some of the risks – of selling profit–shifting advice now impossible to ignore, what are the ethical considerations?

An opportunity for Belgium?

Finally, what can Belgium do? Not such a big fish perhaps, but definitely on the hook. The immediate upside is unexpected tax revenue; the downsides are many.

First, the country stands clearly exposed for antisocial behaviour: profit-poaching in a time of austerity, when the social costs of lost revenues in EU partner countries could not be clearer. Second, trust: how will business view the jurisdiction after this reverse? And third, the stability of the model: given the substantial share of profit booked in the country that appears to have been unwarranted, what are the tax implications of losing the right to tax the non-‘excess’ element?

Here’s the opportunity. The one-off revenues from forcible clawbacks should be sufficient to cover for some time the losses from reduced inward profit-shifting. The question is whether Belgium aims to retain a role in profit-shifting – if it tries to appeal the ruling, struggles to regain credibility with multinationals, introduces and promotes new (OECD- and EC-compliant) mechanisms… or if instead, it takes the opportunity of being ‘caught’, and decides to chart a path towards less anti-social fiscal behaviour.

This could, for example, involve taking a lead in pushing for greater transparency of tax rulings; and in advocating for full enactment of the proposed Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB) and associated proposal for formulary apportionment within the EU, which would eliminate much of the current profit-shifting; and of course publishing country-by-country reporting of multinationals, which would make the extent and direction of it transparent.