It’s possible that there is no more excluded and marginalised group worldwide than people with learning disabilities. In fact, people with a physical or learning disability may often find that they aren’t able to get a job because of this factor. As a result, they are more likely to research into “how much is disability insurance” so they are able to make ends meet when it comes to supporting themselves. This can have a massive impact on their life, especially if they aren’t able to do what other people can do. There are certainly much more harshly and deliberately victimised groups in many places – but for a single group, neglected to the point of rights abuse on a global basis…?

It’s probably not useful to speculate about this anyway, and certainly not to set up any group against any other (and in no way is this speculation intended to downplay other global dimensions of exclusion such as gender and caste).

But here’s the point of thinking about it. If you wouldn’t immediately dismiss the suggestion as ludicrous, then it’s worth thinking about two things:

- Why it might be that the underlying conditions to accept such a pattern of rights abuse might exist, systematically, across all sorts of societies with all sorts of histories and at all sorts of per capita income levels; and

- Whether the exclusion of people with learning disabilities globally has anything like the level of public awareness, attention, or outrage, that it should.

Needless to say, if you buy the premise at all, then these two points have a common causality: the simple lack of importance given to the lives of people with learning disabilities.

Uncounting in the UK

This blog, if it’s about anything, is about the way that the marginalisation of some groups at least is exacerbated by being uncounted. Uncounted, so denied a full role in the statistics upon which policy decisions are made; and in the data which forms the base for political accountability.

Consider one of the world’s richest countries, and one with a long and proud history of universal (universal) health provision: the UK.

Here’s a little context from the last major study:

- On average, men with a learning disability died 13 years earlier and women with a learning disability died 20 years earlier than the general population.

- 37% of deaths would have been potentially avoidable if good quality healthcare had been provided.

Periodically, the exposure of a particularly terrible case of abuse results in commitments to progress. The major recent example is the BBC’s exposure in 2011 of systematic abuse at the Winterbourne View hospital.

Aside from specific legal consequences, this triggered the ‘Concordat‘ – “a programme of action to transform services for people with learning disabilities or autism and mental health conditions or behaviours described as challenging”, signed up to by everyone from the Department of Health and Local Government Organisation, to the Care Quality Commission watchdog and major NGOs in the sector such as Mencap and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation. A particular aim was to move everyone who could live in the community – expected to be the vast majority – out of such institutions, with widespread closures expected.

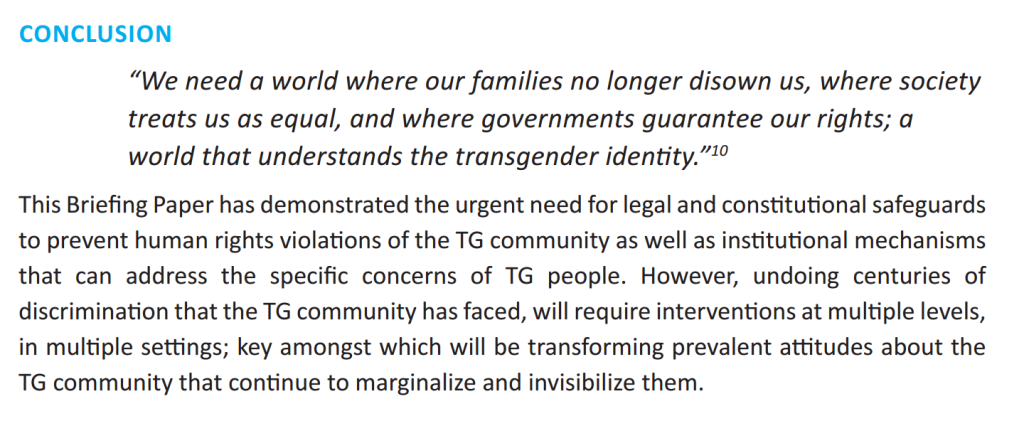

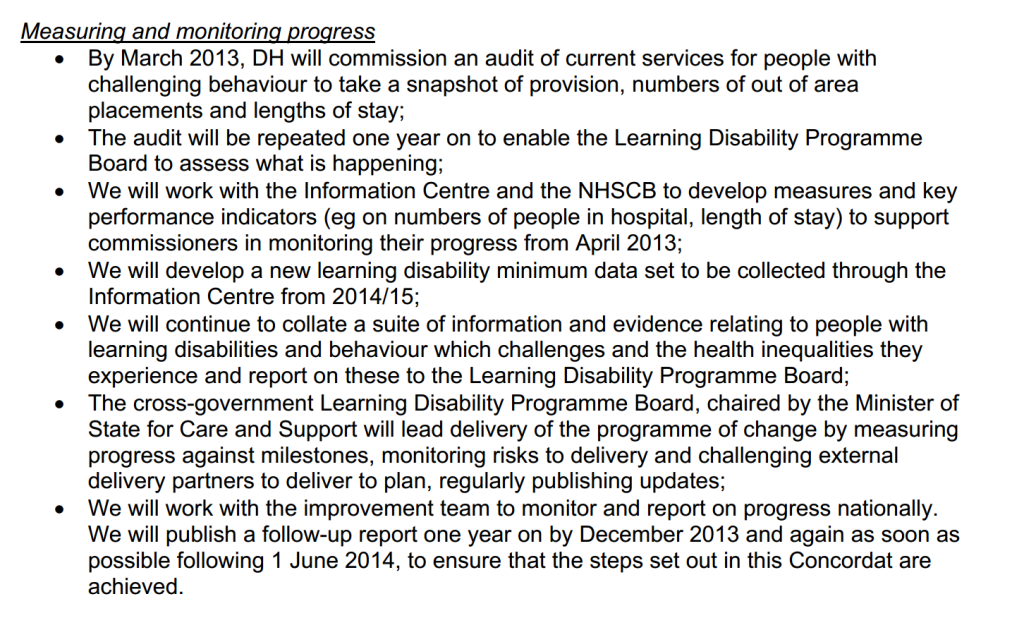

A major component of the Concordat commitments was to better counting. Specifically, the Department of Health committed to:

Within getting into details, these commitments were both welcome in themselves, and indicative of the failure to count to that point.

Lack of progress report

More than two years since the Concordat – and getting on for four years since the motivating scandal broke – what progress has been made?

Earlier this month the National Audit Office published an important report on just this question, examining “the challenge faced in delivering key commitments in the Winterbourne View Concordat, the extent to which these have been achieved, and the barriers to transforming care services for people with learning disabilities.”

There has been a more or less complete failure to achieve the main objective of allowing people to move out of Winterbourne View-type settings and back into real lives, and/or not to enter such settings in the first place. To do what the Concordat aimed for:

a rapid reduction in hospital placements for this group of people by 1 June 2014. People should not live in hospital for long periods of time. Hospitals are not homes.

As the report notes, in 2012 data was a fundamental barrier to progress. Despite some important advances, the findings on the present position are damning.

NHS England lacks adequate and reliable data to monitor progress. In 70% of the 281 case files we reviewed at visits to 4 hospitals, there was at least one error in the June 2014 quarterly census data submitted to NHS England. Official data for our cohort of 281 patients showed an average stay of 3 years and 10 months. The actual length of stay was 4 years and 3 months in their current hospital.

Available statistics are not accurate either about the numbers of people in institutions, nor about even the most basic features of their experience.

This is a repeat, not a typo:

Available statistics are not accurate either about the numbers of people in institutions, nor about even the most basic features of their experience.

It’s difficult not to think that we (still) don’t bother counting, because we (still) don’t care enough to do it right.

A changing landscape?

I can see one reason to be cheerful. Sad to say, it doesn’t come from the big NGOs who are part of the Concordat. Their reaction to the NAO report didn’t seem to include taking any responsibility for its abject failure thus far, nor any suggestion of how their call for change this time would deliver any more progress than all the previous ones. (There’s a whole separate piece to be written about the ability to hold governments accountable of large NGOs with an existential dependence on public funding for service provision.)

No, if there’s a bright spot here, it comes from a quite different direction. The Justice for LB campaign, coming out of the completely unnecessary death of 18-year-old Connor Sparrowhawk in ‘care’, has developed into a grassroots movement of people living with disabilities and their families. [Full disclosure: Connor lived across the road and I love these guys.]

Justice for LB responded to the NAO audit of the Winterbourne Concordat with their own self-audit, which is (surprisingly!) a thing of beauty, anger and hope. The potential for the ‘LB Bill‘ to make it into parliament after the general election is real, and exciting.

Perhaps the best way to stop being uncounted is to demand it yourself – but of course if it were that easy, nobody who wanted to be included would be left out in the first place. Uncounted is a political phenomenon, and Justice for LB is a most welcome, and deeply political response.

To end:

To end: