Transparency International has a new report out on the extent of secretive offshore ownership of London and UK property – and the consistent appearance of more secretive jurisdictions in investigations of corrupt ownership. Back of the envelope calculations suggest the tax implications could be substantial too… This may not make sense to some, as to start a company legally has more than just one advantage to forming a company in the UK and complying with the many regulatory boards that govern different Public and Private Limited Companies.

A few top lines:

- The scale of offshore ownership is large, covering 40,725 London properties. (Or per the Financial Times last year, at least £122 billion across England & Wales; for Scotland, check Andy Wightman’s blog and book.)

- Secrecy is a common feature. 89% of these properties (36,342) are held through

secrecy jurisdictions, with more than a third due to the highly secretive British Virgin Islands alone.

secrecy jurisdictions, with more than a third due to the highly secretive British Virgin Islands alone. - Secrecy jurisdiction structures account for 5-10% of properties in the richest parts of the city including Westminster and Kensington & Chelsea: see map.

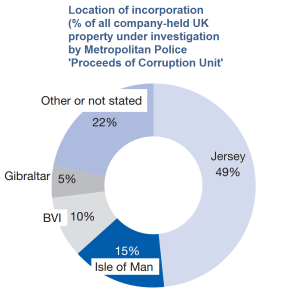

- To the surprise of nobody, secrecy jurisdictions dominate the ownership of property in the Metropolitan Police’s investigations of corruption too.

The report is well worth a look, and details a lot more of the ways in which secrecy jurisdictions are used to make ownership anonymous, and how that facilitates all sorts of corruption.

Just for fun, I took a couple of the stats and checked to see what the potential capital gains tax (CGT) implications might be – because of course if a property is owned through an anonymous company, you can sell the company rather than the property and potentially skip the tax.

A lot of offshore ownership will be entirely unsullied by any intention to launder the proceeds of crime, or to dodge tax. But to get a sense of scale, it’s still informative to think in terms of the potential CGT at risk.

Example 1: the report notes that in 2011 alone, BVI companies bought £3.8 billion of UK property. Assume that property rose in value according to the government’s average house price index (although we know this is mainly high-end property, so this is likely to be conservative), then the rise in value by 2015 would be around 11.8%. Applying CGT at 28% would yield around £125 million of revenues – from the offshore ownership via one jurisdiction and in one year alone.

Example 2: taking the same approach to the FT’s figure of £122 billion owned offshore in England & Wales last year, we have an average rise in value of around 1.9%, with a potential CGT yield for the year of nearly £2.3 billion.

Of course, in neither case do we expect all CGT to have been unpaid; and the liability would only arise were the property sold. Still – the potential scale suggests TI’s final recommendation might well pay for itself, or indeed do rather better:

The Land Registry should publish the ultimate beneficial ownership of these properties freely to the public, on the same basis as Companies House is set to do under current UK legislation. Accordingly, companies registered overseas would be required to update beneficial ownership information on the same basis as UK registered companies.

And so say all of us.