In a strident blog at the International Centre for Tax and Development, Mick Moore, Nora Lustig, Richard Bird, Nancy Birdsall, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Richard Manning and Wilson Prichard have called for the rejection of post-2015 tax targets. (Full disclosure – I work with the ICTD, including on the Government Revenue Dataset.)

Seven leading thinkers on development and tax can’t be wrong – can they?

The case against

The Zero Draft of the Outcome Document suggests that “… Countries with government revenue below 20 per cent of GDP agree to progressively increase tax revenues, with the aim of halving the gap towards 20 per cent by 2025.…”

It would be a great mistake to encourage quantitative tax targeting of any kind. It would be like reintroducing the kind of production targets that did so much damage in the former Soviet Union.

This position rests on three arguments:

First, it is already a significant problem in developing countries that most tax agencies are already subject to a single performance measure: the extent to which they achieve the cash targets for revenue raising set by ministries of finance…

Second, increasing revenue collection will likely in some countries lead to an increase in poverty… It is not uncommon that the net effect of all governments taxing and spending is to leave the poor worse off…

The third objection is that, in many cases, the figures used to assess performance in relation to these targets may be almost meaningless.

Background

I’ve posted on this before, in response to a request on what would be the best post-2015 tax targets (taking for granted that there would be some kind of a tax target).

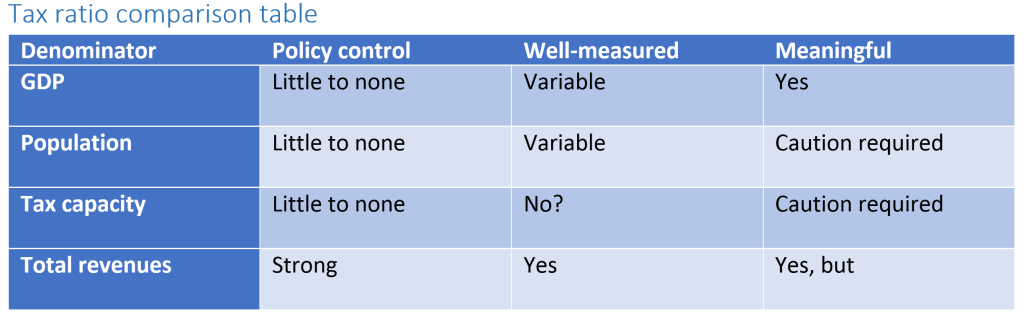

The limitations of the tax/GDP ratio should give us pause, and so it is useful to consider alternative denominators in particular – not least the tax/total revenues ratio, which is associated with improvements in governance. This was the conclusion:

[F]or all its issues, the tax/GDP ratio is probably worth sticking with; while the tax/total revenues ratio is an important complement.

But maybe I should have been more cautious about having any target at all…

A useful intervention

There is a legitimate debate about whether there are too many goals and targets in the proposed SDGs (not to be confused with the pretty feeble argument sometimes heard that we should ‘stick with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)’, and ignore difficult things like inequality).

There has been a tendency to think that any important issue needs a target – and it may not be true.

Not all important issues have a clear consensus on the right value to target. Even a pure ‘bad’ like infant mortality may more usefully have a positive, rather than a zero target. So it’s possible that tax – reflecting the complexities of state-citizen relations as well as economic structure – simply doesn’t lend itself to a target.

But: the individual elements of the critique seem overstated, so it becomes hard to support the authors’ stark conclusions.

To recap, they argue that a tax target is a bad idea because

- it’s a blunt tool that risks the wrong prioritisation;

- tax may be bad for poverty, so more of it may be worse; and

- we measure both components of the proposed tax/GDP target too badly.

Criticism 1. Too blunt?

The first criticism is that the tax/GDP target is too blunt. Tax authorities can already face too much pressure around a single measure (cash collections). Might tax authorities be put under such pressure to reach a tax/GDP target that they undermined broader progress on e.g. taxpayer trust, revenue diversification or stability?

Diversifying the performance criteria for tax collectors is vital. Some developing countries are making progress. Any kind of international blessing for archaic practices would be a mistake – and perverse in terms of the Sustainable Development Goals.

This is clearly a legitimate concern. But it’s hard to feel comfortable with it being used to draw such a stark, final conclusion as that there should be no target at all.

The whole SDG process requires finding the best individual targets to reflect political priority in important areas. Almost by definition, these cannot reflect the perfect, broader dynamics in any of those areas. And this is not their role.

Would a tax/GDP target really be ‘archaic’, and ‘perverse’?

As the authors note, there is currently excess pressure on cash collection targets. Could one international target (among many) overtake this existing domestic political pressure? If it did, would a tax/GDP target (for which there is some evidence of association with development) be worse than a cash collection pressure (for which there is none)?

And what if the target was instead on tax/total revenue – which tends to support accountability over time? Or what if we included additional targets (as I suggested), or nested indicators, that reflected some of the other aspects?

Criticism 2. Bad for poverty?

This criticism rests on Nora Lustig’s important findings from the valuable Commitment to Equity (CEQ) project, namely that some countries’ tax and transfer systems leave people living in poverty worse off.

This is clearly of great importance. If more tax led to more poverty, a (positive) tax target would be obscene.

But I don’t think the authors of this post hold that view – in fact, quite the reverse. As Mick wrote earlier this year: “The developmental benefits of governments taxing citizens, even for modest sums, are often disregarded.”

And nor does the evidence support a broad pattern of taxation worsening poverty.

The problem that the blog authors highlight is that “the number of poor people who are made poorer through the taxing and spending activities of governments exceeds the number who actually benefit”, in Armenia, Bolivia, Brazil, El Salvador, Ethiopia and Guatemala.

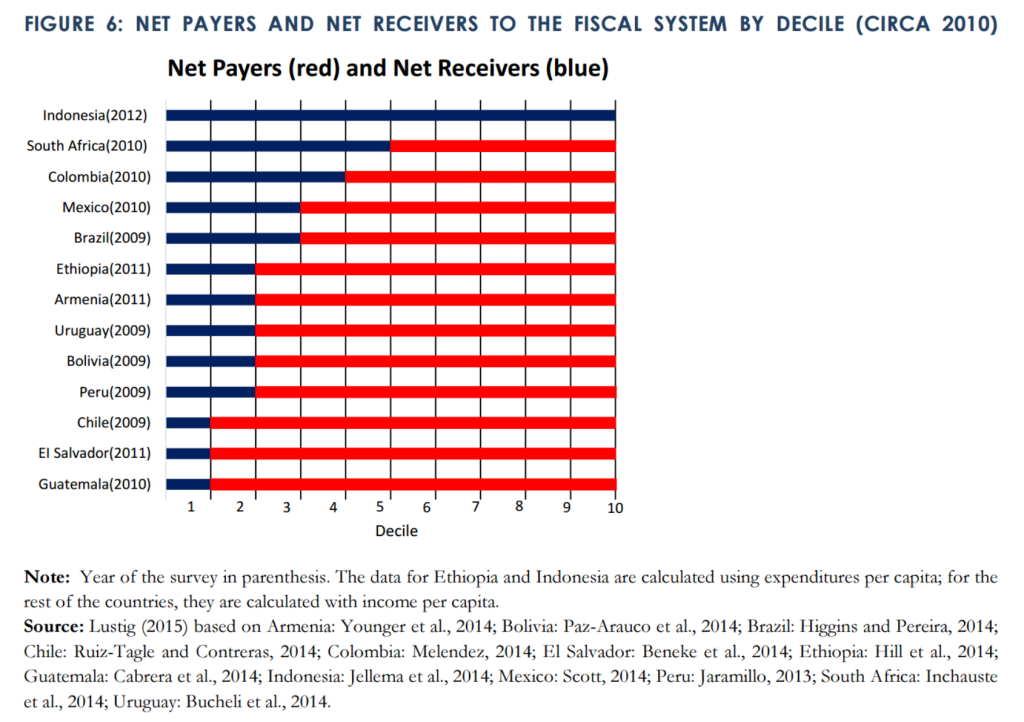

I couldn’t see the claim stated as such in the CEQ paper linked, so it’s a little hard to be sure. But what it does show is the pattern of net receivers and net payers in figure 6:

Now where the $2.50 absolute poverty line falls above the blue/red changeover in the cases mentioned, it implies that some of the people below that line are absolute losers from the tax and expenditure system. (Directly only – the analysis doesn’t look at broader benefits of taxation, such as improved long-term government accountability, which may be of particular benefit to those living in poverty, as opposed to elite insiders.)

Now where the $2.50 absolute poverty line falls above the blue/red changeover in the cases mentioned, it implies that some of the people below that line are absolute losers from the tax and expenditure system. (Directly only – the analysis doesn’t look at broader benefits of taxation, such as improved long-term government accountability, which may be of particular benefit to those living in poverty, as opposed to elite insiders.)

The CEQ analysis also finds that expenditures in developing countries are broadly progressive, and becoming more so. What we can tell from figure 6 is that in all cases examined, the poorest appear to do best (that is, net receivers are always at lower income levels than net payers). Where there are high levels of absolute poverty, some systems are insufficiently progressive to ensure that the better-off of those living below the poverty line are also net winners.

From this, the blog authors conclude:

The big risk in setting tax targets is that governments will then strive to reach them – and in the process impoverish poor people even further.

Clearly, there is a risk that governments raise (more) tax without making it (more) progressive. But is this really ‘the big risk’?

Consider draft SDG target 10.1:

by 2030 progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40% of the population at a rate higher than the national average

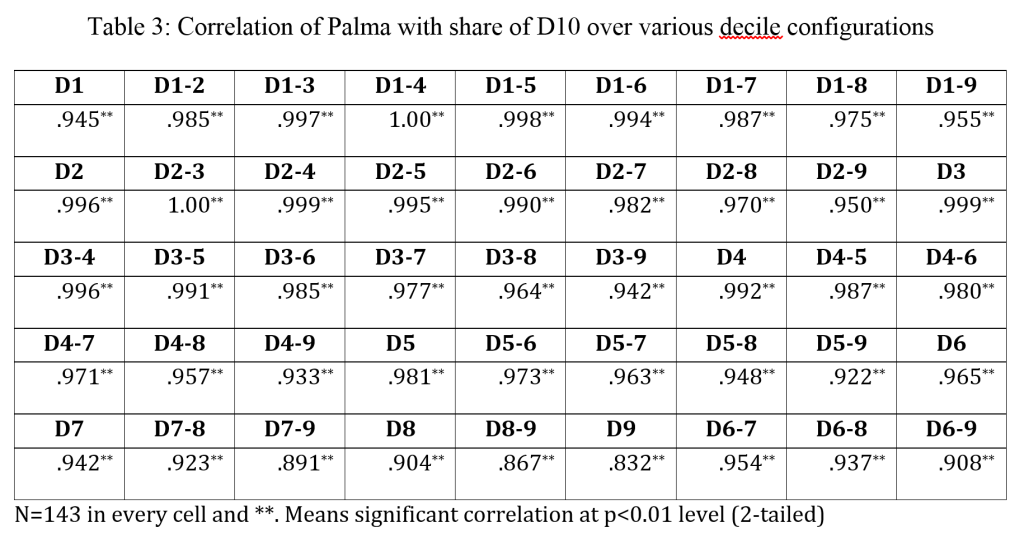

Indicators under discussion for this include pre- and post-tax and transfer income shares of the top 10% and bottom 40% (yay Palma).

It seems unlikely that a tax/GDP target would take precedent over 10.1, such that regressive taxation is pursued in order to hit the tax target. And on balance, you’d expect the progressive of taxes and transfers to improve (or at least, not to deteriorate) with a rising tax/GDP ratio.

So again, I think the authors raise an important point to think about, but then draw such a stark conclusion that it’s hard to support.

Criticism 3. Too badly measured

The third criticism made is that GDP in particular is too badly measured, and tax too open to manipulation, for tax/GDP to provide a decent basis for target. (Per my earlier piece, the denominator is also not in policymakers’ control.)

The authors note the extent of GDP mismeasurement, and what I hope is a uniquely egregious example of tax timing manipulation, as well as the instability associated with e.g. resource revenue volatility.

Accounting and reporting games are already being played around tax collection targets. If the international community were to popularise the idea that an improved ratio of tax collection to GDP is intrinsically a good thing, we can expect more such games.

This seems to be the strongest, and also the least over-stated, criticism.

Here’s the thing though: substitute other words for ‘tax collection’ in the quote, and it still makes sense.

The measurement of a great many aspects of the MDGs – never mind the SDGs – is open to manipulation. Tying this to public accountability for performance is, yes, likely to result in more manipulation (see e.g. the contrasting measures of educational enrolment in Kenya; or consider how the much-celebrated dollar-a-day poverty target was successively re-engineered to allow increases of hundreds of millions of people in the target numbers living in extreme poverty).

In addition, there are a great many proposed SDG targets for which data is – currently – not good enough. I hope there is also a general consensus that this time, the targets should be chosen on merit and the measurement then addressed; rather than allowing the existence of data to dictate what targets are set, as with the MDGs.

So the criticism is fair, but it doesn’t follow that this is a reason not to have a target. (If it were such a reason, the entire SDGs project – and the MDGs before them – would be open to question…)

Long story short(ish)

The intervention from the seven authors of the ICTD blog raises a set of important questions, and these merit further attention in the design of a post-2015 tax target. As they suggest, tax should almost certainly be better and more diversely measured, as well as more progressive.

What the intervention does not, however, provide, is substantial support for the conclusion that introducing a tax target would be a mistake.

Like the MDGs, the SDG targets will not be universally pursued – never mind achieved. What they will do, if successful, is establish important norms that will in turn drive broad progress.

There’s no question that the MDG model was seriously flawed in its reliance on aid as the implicit source of finance. Flawed, because aid could only ever have formed a small part of the solution; and flawed because of the politics (note that progress only really got going in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, with the mid-2000s adoption of MDG targets into national planning processes – where they began to exert substantial influence on budget decisions).

We can, and should, design better tax targets. But domestic taxation must be central to Financing for Development in post-2015.

Dropping tax targets completely would be, by far, the bigger mistake.