The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has revealed the basis on which it ranks jurisdictions as low or high risk for money laundering – and it seems inevitable that it will support debanking of poorer countries.

AML rules under pressure

First a little context. There has been growing pressure lately on anti-money laundering (AML) rules. In recent years, a string of major banks has faced large fines for apparently systematic sanctions-busting. This has been followed by a pattern of withdrawal – ‘debanking’ – from a range of countries where the risks of inadvertently channelling funds of sanctioned and/or terrorism-related entities and individuals have come to be seen as too high.

On the one hand, there are reasons to be rather cynical about this process. First, because supporting generally small-scale remittances to Somalia, for example, is a far cry from accepting and anonymising Iranian funds – and presumably much less profitable. And second, because it feels a little convenient for major banks to be making a case for reduced financial regulation, in which their interests align with those of some of the world’s poorest people.

On the other hand though, there are good reasons to take the issue seriously. (Disclosure – I’m on a CGD working group looking at just this question, so I would say that…) First, even if debanking is motivated by relative profitability of Somalian remittances compared to Iranian sanctions-busting, the potential development impact of remittance channels becoming more expensive is nonetheless substantial. (And we surely don’t expect banks not to respond to profitability.) Financial inclusion also seems to be associated with lower inequality.

And second, we should take the issue seriously because ultimately we want AML rules that work, for everyone, and demonstrably so – which is not the case now.

The question is not whether and how AML rules should be relaxed. It is this:

How can AML rules be designed so that the risks facing banks and other financial institutions are proportionate to the risks of carrying criminal flows, and not inadvertently supporting discriminatory outcomes against poorer countries (and people)?

An inexplicably bad approach

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is accountable to HM Treasury and the UK parliament for regulating more than 50,000 firms to ensure integrity of financial markets. As Matt Collin points out in a great post, the FCA has just fined the (British branch of the) Bank of Beirut £2 million, and ordered it to sort out its AML procedures.

In the interim, the bank is barred from taking on new business in ‘high risk’ jurisdictions – which the FCA defines as anywhere scoring 60 or less out of 100 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

Matt makes two important points about the weaknesses of this approach:

- The CPI doesn’t reflect AML risks. Not a single one of the surveys which are aggregated into the CPI involves perceptions of money-laundering.

- The threshold is arbitrary – and includes nearly 80% of the 175 countries for which ratings are produced. See Matt’s great figure.

Let’s add a couple of other points:

- Even on its own terms, the CPI is a very bad measure of corruption. Sorry and all, and I think many TI chapters do really fantastic work; but the quicker the organisation drops the CPI, the better. Nor should anybody else be using it, as if it were some kind of objective indicator of corruption (never mind money-laundering) – it’s not.

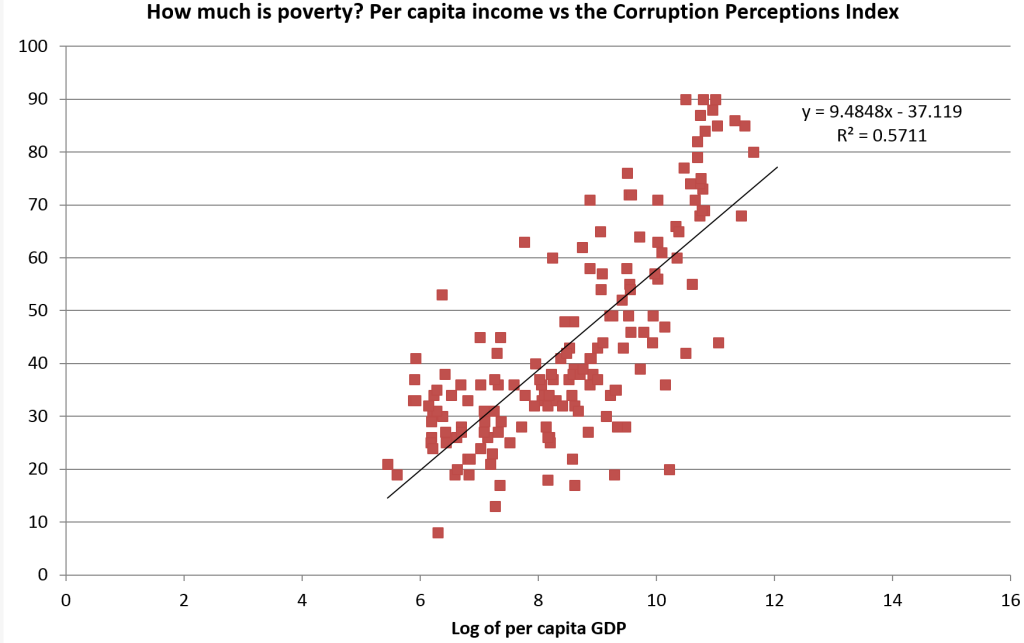

- And here’s the real kicker. The CPI is mainly telling you one thing: how poor a country is. Per capita income ‘explains’ more than half of the variation of the CPI (for 2012, which I happened to have to hand). The equivalent for the Basle Anti-Money Laundering Index, which includes the CPI among its components, is a little over a third.

So: the FCA is basing their AML risk measure on an arbitrary threshold, in a bad measure of corruption, which has nothing to do with money laundering, and mainly reflects income poverty.

An alternative approach

What could the FCA do instead? Well, they could use the Basle index. Or they could follow the lead of researchers at the Italian central bank, or a German rating agency among a good many others – and use TJN’s Financial Secrecy Index (FSI).

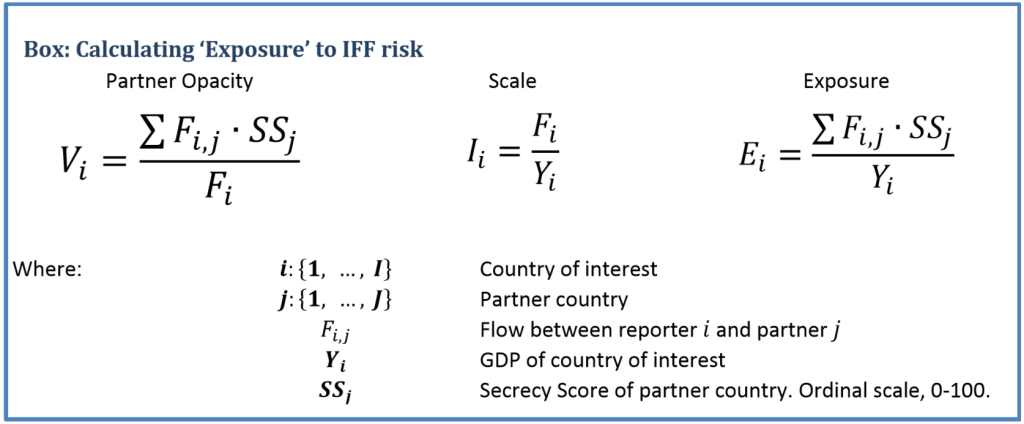

The FSI – which is also a component of the Basle index – brings together 48 variables, predominantly from assessments by international organisations, to create 15 indicators of financial secrecy – that is, of the risk factor for money-laundering, tax fraud and other financial crimes. These are then compiled into a single ‘secrecy score’.

For the FSI, this is combined with a measure of each jurisdictions’ global scale in order to produce a final ranking that reflects the relative potential to frustrate other countries’ regulation, taxation and anti-corruption efforts.

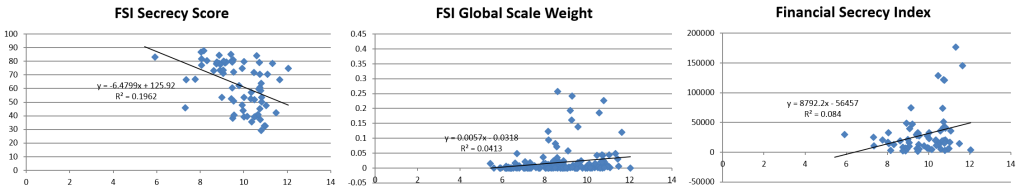

For a risk measure, you’d only want to use the secrecy score (or perhaps a subset of indicators that are most tightly relevant to money laundering). Relationships with per capita income are much weaker and of mixed direction, reflecting the basis in objectively assessed secrecy and scale criteria rather than perceptions of corruption.

Conclusion

Conclusion

To recap: If a financial regulator were to design a simple risk measure that would be most likely to lead to debanking of poor countries, while at the same time having no impact on the most risky jurisdictions, it’s hard to see how they could have done better than the FCA.

The broader lesson for the necessary rethinking of AML rules seems fairly clear. What are needed are context-sensitive measures that encourage responses proportionate to the actual financial crime risks – rather than encouraging the blanket withdrawal of services to poorer countries and/or people.