[A long post, building to an Uncounted proposal on UK inequalities monitoring and data.]

Last week’s UK election produced a majority for the centre-right Conservatives – a majority of parliamentary seats, that is, albeit with 36.9% of votes.

Framing a victory

The winning framing seems to have been one of Conservative economic competence, set against two claimed threats from change:

- a ‘coalition of chaos’ featuring Labour and the Scottish National Party (despite the 2010-2015 Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition having set something of a modern precedent in UK politics, and both Labour and the SNP having explicitly ruled out a coalition); and

- a return to Labour’s crisis-inducing economic incompetence (despite a fairly broad expert and academic consensus that Labour’s economic policy before and through the crisis was pretty reasonable; and that the the 2010 coalition’s austerity measures, largely abandoned in 2012, were a triumph of ideology over economic commonsense, with predictable macroeconomic and human costs).

Much has been written, and much more will be, on the reasons for the framing success – including the breadth of media support for a Conservative victory, and not unrelated, the ‘mediamacro myths‘ per Simon Wren-Lewis that ensured popular perceptions of economic (mis)management remained far adrift of expert analyses.

Lost in construction?

The campaign featured more heat than light on the impacts of austerity, and the related inequalities. Everyone said they’d reduce tax avoidance, some said they’d reduce tax evasion, but there was barely a specific policy proposal among the lot.

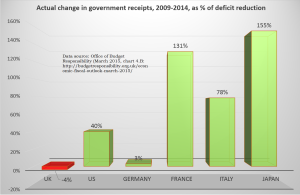

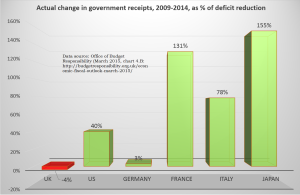

Nobody mentioned that the 2010 UK government had been the only major economy to cut tax during austerity – so that spending cuts were, uniquely, greater than the deficit reduction that was achieved.

Nobody mentioned that the 2010 UK government had been the only major economy to cut tax during austerity – so that spending cuts were, uniquely, greater than the deficit reduction that was achieved.

In terms of either broad inequalities (e.g. income and wealth), or specific ones facing marginalised groups such as people living with disabilities, the campaign featured little in the way of detailed discussion.

Marginalisation in (as?) policy design

Jim Coe has written a typically thought-provoking piece on the challenges facing broadly progressive activists in the UK now.

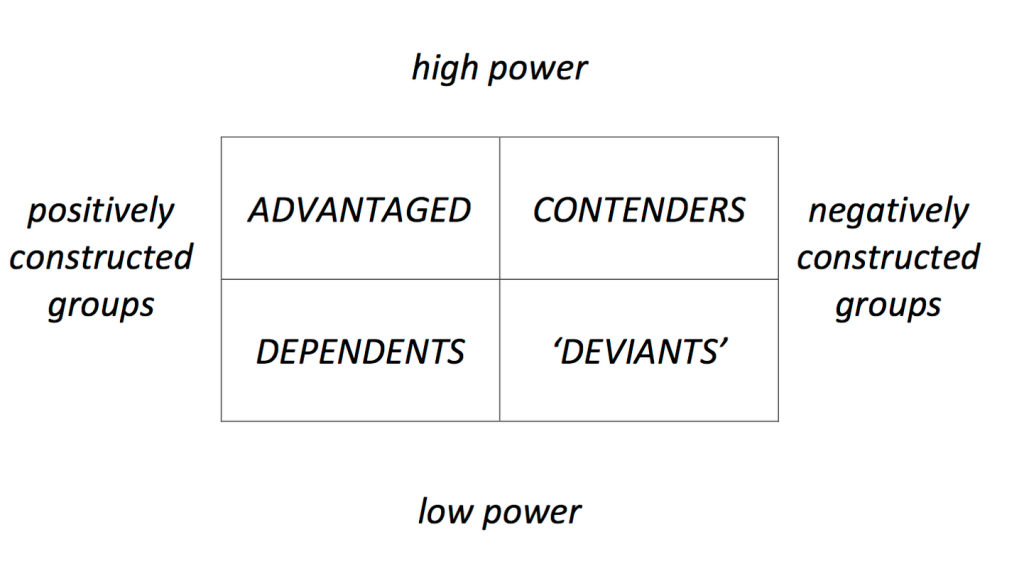

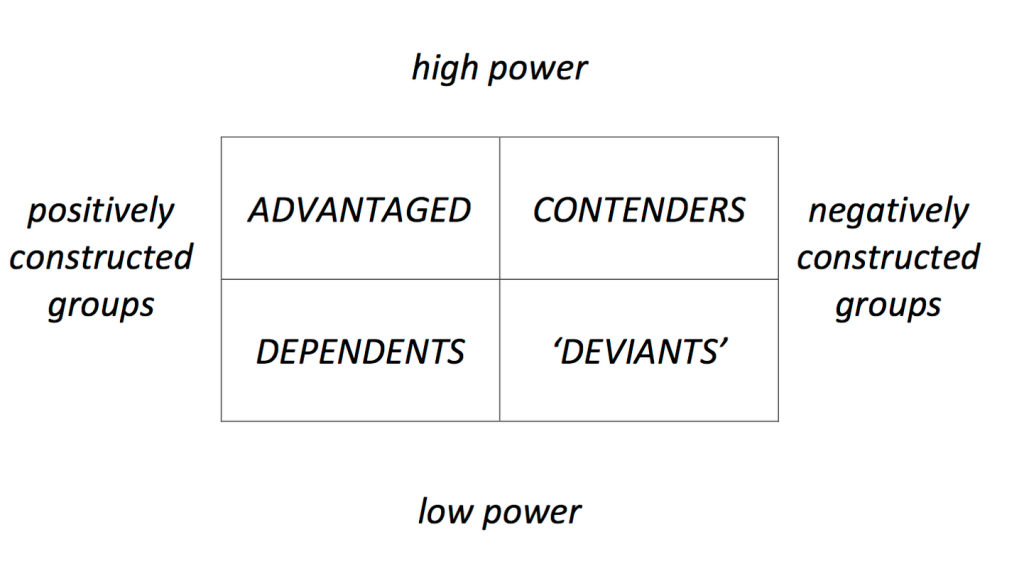

Jim looks at a model of four groups in terms of (i) their respective power and (ii) the extent to which they are ‘socially constructed’ as deserving policy support or not:

- Advantaged groups – such as small businesses, or homeowners – are treated with respect and perfectly placed to receive policy benefits.

- Contender groups – such as some in big business (bankers etc) – are not seen so positively. But, because they are powerful, they can gain hidden benefits whilst resisting attempts to impose policy sanctions.

- Dependents – groups who require some kind of support, students, workers on low pay – are seen generally positively but lack political power. They may be viewed as ‘good people’ but the support offered will often be inadequate, and they lack the influence to make enhanced claims.

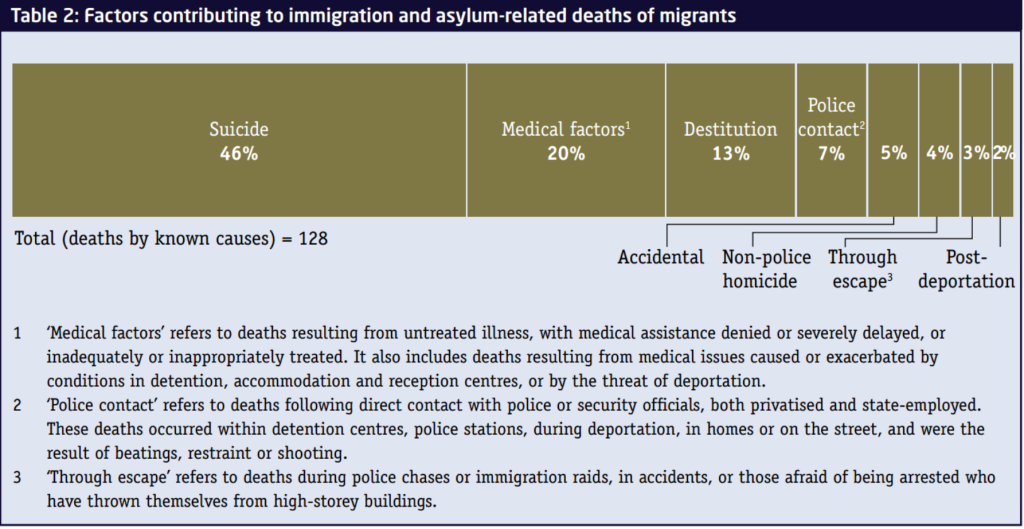

- ‘Deviants’ both lack power and are negatively perceived. The list of groups who fall in this category seems to be ever-growing. Criminals, drug users, and, increasingly, many migrant groups, and families in poverty, etc. etc. Few speak on their behalf and policy makers are reluctant to be seen providing ‘good things to bad people’.

Jim’s post is well worth reading, as he builds from here to discuss the ways in which positions can be self-reinforcing over time, and what the strategies may improve the prospects for reversal or resistance in particular aspects. I want to make a comment and a proposal.

Austerity and uncounting

There is presumably always pressure, in the model above, to squeeze those in the low power group deemed deserving of policy support, into the undeserving group: in the model’s terminology, to see dependents increasingly as deviants.

In the context of a commitment to austerity – whether economically sensible or not – there is a specific need to reduce the total of policy support, potentially giving rise to a political climate which sets those with power (more) strongly against those without.

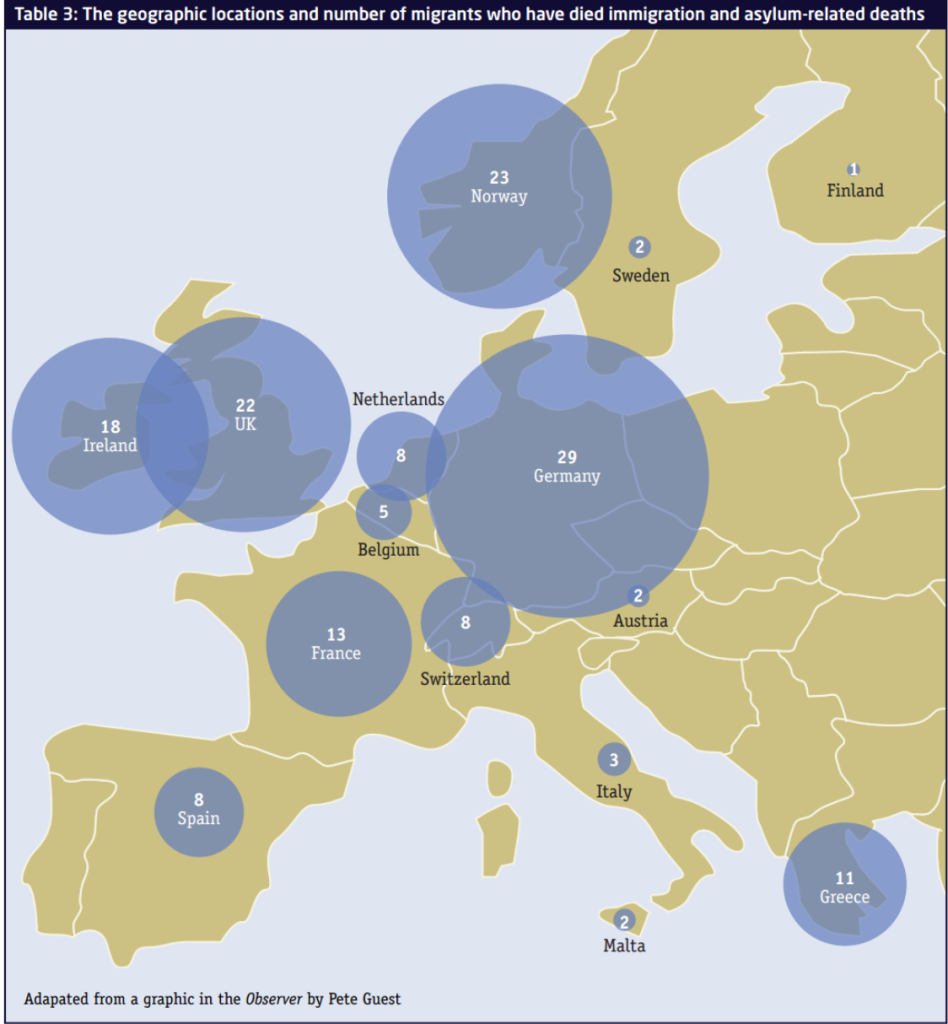

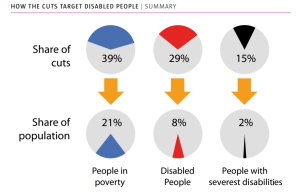

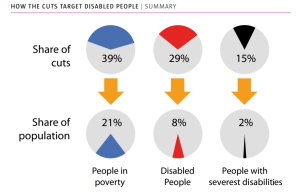

In the UK the growth in abuse directed at people living with disabilities, including learning disabilities, is a particularly damning feature of this trend – along with the disproportionate cuts in benefits applied. The rise of explicitly anti-immigrant positions across the major political parties is another.

In the UK the growth in abuse directed at people living with disabilities, including learning disabilities, is a particularly damning feature of this trend – along with the disproportionate cuts in benefits applied. The rise of explicitly anti-immigrant positions across the major political parties is another.

A flipside of this that one might expect to see is a (quiet) reduction in the fiscal contribution of those with power – perhaps explaining the UK’s real reduction in tax revenues, though not necessarily why the UK is an international outlier in this regard.

The incoming government has committed to sharper cuts than it managed in the previous parliament: with a similar revenue trajectory, the risk is of a significant worsening in inequalities, and the weakening more generally of the state’s capacity to deliver support to ‘dependent’ groups.

Finally, Jim’s model provides one more way of thinking about the phenomenon of Uncounted (the importance of power for being counted, and vice versa).

This last parliament has seen some fairly striking uncounting – none more so than the decision to stop collecting statistics on the deaths of those receiving certain benefits, but the continuing failure to implement fully the government’s own review recommendations about statistics on lives and deaths of people living with learning disabilities should not be overlooked either.

Failing to count bad group outcomes represents a substantial worsening of the inequalities faced – but often a politically beneficial one for governments.

A modest proposal

Without getting into party political issues of leadership direction, are there reasonable measures that would support greater accountability to limit damaging inequalities in the current parliament, and promote greater attention to these issues in future political debate?

The one that springs to mind is simply to track the data – its existence or otherwise, and its values where it does exist – on each of the major inequalities in the UK.

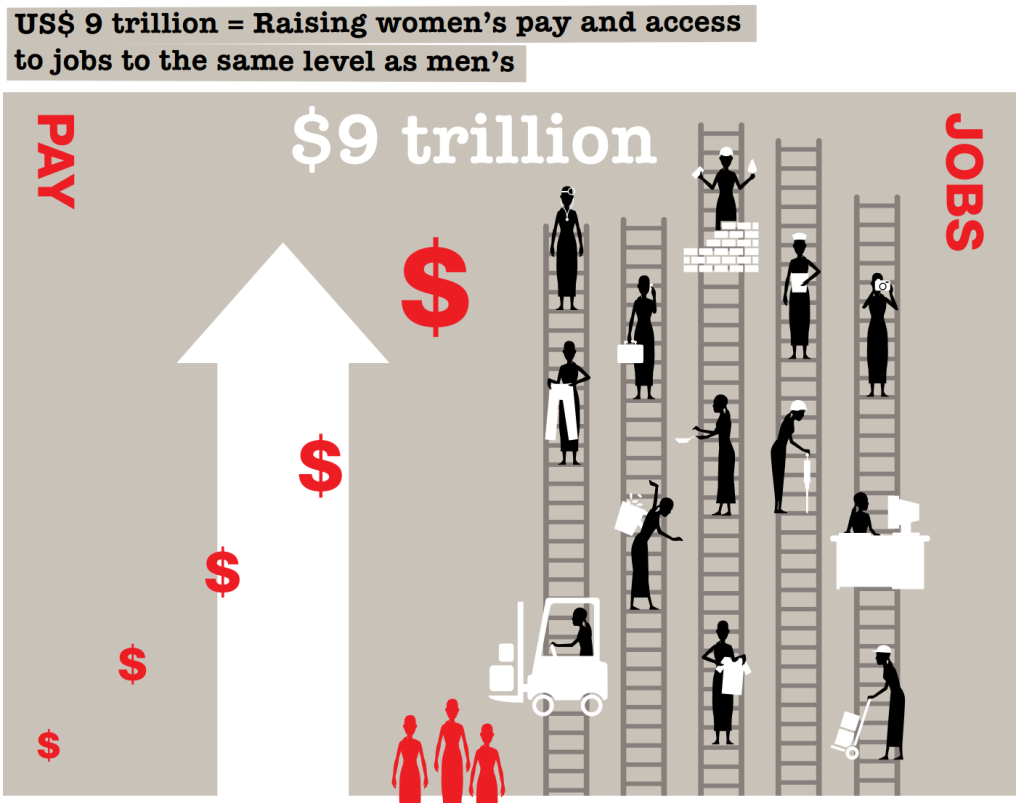

The high-level group that David Cameron co-chaired on the post-2015 successor to the Millennium Development Goals was absolutely clear on the importance of disaggregated data to ensure that all groups and people benefit:

The suggested targets are bold, yet practical. Like the MDGs, they would not be binding, but should be monitored closely. The indicators that track them should be disaggregated to ensure no one is left behind and targets should only be considered ‘achieved’ if they are met for all relevant income and social groups. We recommend that any new goals should be accompanied by an independent and rigorous monitoring system, with regular opportunities to report on progress and shortcomings at a high political level. We also call for a data revolution for sustainable development, with a new international initiative to improve the quality of statistics and information available to citizens.

My pie in the sky is that groups like the Resolution Foundation, Centre for Welfare Reform, #JusticeforLB, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, UK Women’s Budget Group and others, might collaborate to ensure the following:

- A baseline of available UK data on a full range of aspects of human development, fully disaggregated as Cameron’s panel demanded, showing levels of inequalities and also gaps in data, as at 7 May 2015; and

- A tracking and ongoing analysis of changes in that data and its availability over the course of the current parliament (and ideally beyond).

Naturally, this would be a fully open data pie in the sky, and ideally one or more groups like Open Knowledge Foundation would play a role too.

To end:

To end: