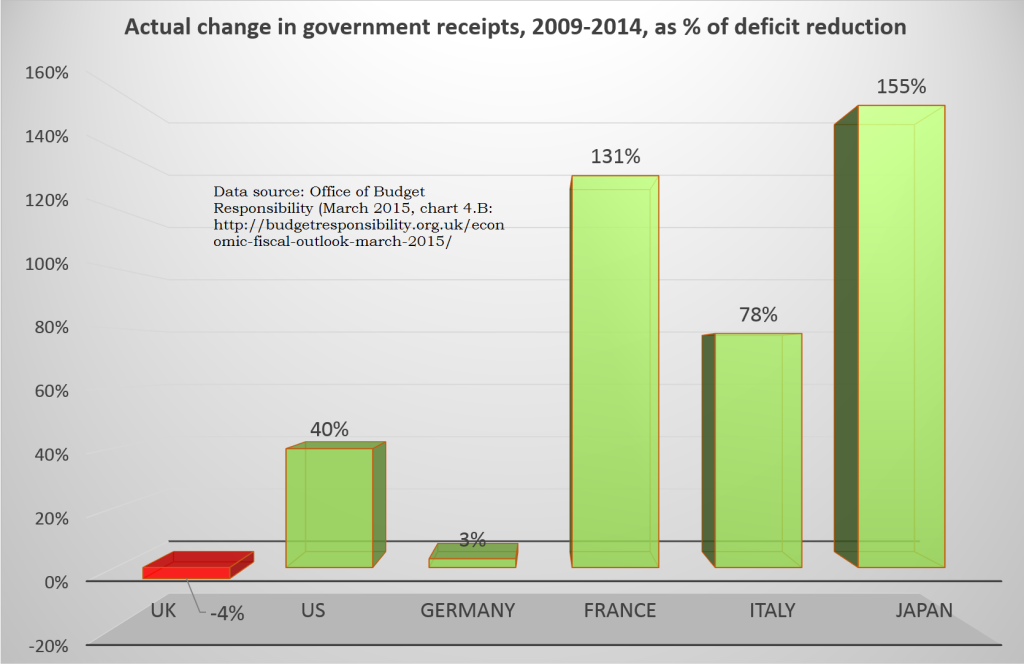

The UK is the only leading economy which didn’t split its deficit reduction between spending cuts and tax rises. To put that another way, the UK is alone in having imposed spending cuts larger than the deficit reduction it achieved, because receipts actually fell.

This curious point was noted by the Office of Budget Responsibility (see chart 4.B and discussion) in its analysis of the last budget of the current UK parliament, though not widely picked up. Big hat-tip to James Plunkett for flagging it:

How does UK deficit reduction compare to other countries? This whole para from the OBR is quite revealing: pic.twitter.com/FND8S9NKbT

— James Plunkett (@jamestplunkett) March 18, 2015

So the UK’s austerity has been particularly tax-averse. Does it matter?

Inequality impact

There’s a lot of detail hidden under this headline number, including the broad shift away from direct taxation. Corporate tax cuts, in particular, have reduced those revenues by more than 20%.

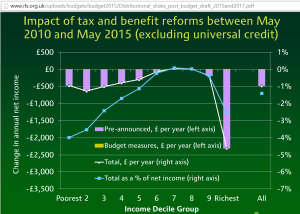

While spending cuts and tax rises can both be regressive, you expect in general that spending cuts affect lower-income households more; while tax rises would affect higher-income households more.

All else being equal, you’d expect a relatively extreme tax-averse austerity to have a regressive impact. And, by and large, this is what the data show. The Institute for Fiscal Studies find that the ‘biggest losers’ are the bottom half of the distribution, due to cuts in social security for those of working age, and the top decile (due to tax rises – a finding that is much stronger when the tax rises of the previous Labour government are included in the analysis).

The blue line in the IFS figure (using the right-hand axis) shows the rather greater relative losses of the bottom 40% compared to the top 10%. [Consider the Palma ratio of inequality to see why these groups are especially significant.] The bottom quintile in particular is hardest hit – and inevitably much less able to assimilate a few percent loss than would be the top decile.

It’s not clear whether policymakers or opposition parties are aware of, never mind engaged with, the relatively extreme tax-averse nature of UK austerity.

This is probably in part because the sharp inequality fall from 2008-2011 due to the crisis, rather than (changes in) policy, has allowed the current government to pursue a relatively regressive approach while still claiming progressive impact.

It’s disappointing though to see the lack of scrutiny of, or public justification for, such an approach.