The governments of G8 and G20 countries gave the OECD a global mandate to deliver country-by-country reporting, as a major tool to limit multinational corporate tax abuse, and with particular emphasis on the benefits for developing countries.

New evidence shows that – even before its implementation – the OECD standard is likely to worsen existing inequalities in the international distribution of corporate taxing rights. That is, OECD country-by-country reporting may be so skewed that it will strengthen the relative ability of its rich country members to tax multinationals, at the expense of developing countries.

The powerful potential of CBCR

‘Uncounted‘ is my shorthand for the view that who and what get counted, or not, is both a driver and a reflection of power inequalities. The failure to count marginalised groups reflects their lack of power, and also undermines the prospects for the inequalities they suffer to be addressed. The failure to count powerful groups – say, the income and assets of the top 1% – reflects the extent of their power, and also undermines the prospects of challenging the inequalities they benefit from.

The requirement for country-by-country reporting (CBCR) by multinational companies should be a paradigmatic example of transparency for accountability, where openness becomes a tool for meaningful challenge to injustice.

The Tax Justice Network has taken CBCR from the practically unheard of in 2003, when we began to develop a detailed proposal with Richard Murphy around the time of our founding, to the global policy agenda when in 2013 it formed an important part of the workplan for both the G8 and G20 (see film at 2 min 50 in particular).

The case for CBCR is that it provides additional, public information on the location of the activities of multinational companies, in order to improve accountability in a range of ways.

First among these is tax. Multinationals can be held to account against the global aim of improving the alignment between where their economic activity takes place, and where taxable profit is declared.

Openness of CBCR to tax authorities allows measures of misalignment to be easily calculated, in order to identify the major tax risks. Openness of CBCR to the public allows media and civil society activists to hold tax authorities to account; and allows investors and market analysts to identify share prices risks and so price multinationals more efficiently.

In this way, public CBCR is a transparency measure that genuinely shifts power, and drives greater accountability in multiple channels.

The disappointments of OECD CBCR

Sadly, the OECD approach demonstrates just how the undermining of a transparency measure can exacerbate inequalities and weaken accountability.

First, the power of lobbying saw the idea of public reporting knocked on the head – so at least in the OECD standard, there’s no commitment to allow investors, analysts, journalists or activists the opportunity to hold multinationals accountable.

Second, things went even further into reverse when the OECD agreed – almost unbelievably – not to support individual tax authorities asking for CBCR from multinationals operating in their jurisdiction.

Think about that for a moment: so successful has been the lobbying against potential accountability, that something tax authorities could have done unilaterally before the OECD got the CBCR mandate, would now be seen as counter to the international standards.

Instead, tax authorities of host countries are expected to apply for the information to be provided by the tax authority of the home country – if the latter has it, if there is an information exchange protocol in place, if the host country has committed to confidentiality (no way back into public openness here).

New evidence

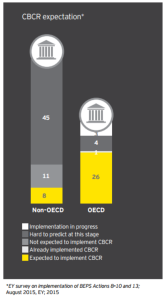

And now accounting firm EY has published the results of a survey on implementation of CBCR. The new evidence appears to confirm strongly the fear that each watering down of CBCR at the OECD will be to the detriment not only of openness and accountability, but also to the taxing rights of non-OECD members.

And now accounting firm EY has published the results of a survey on implementation of CBCR. The new evidence appears to confirm strongly the fear that each watering down of CBCR at the OECD will be to the detriment not only of openness and accountability, but also to the taxing rights of non-OECD members.

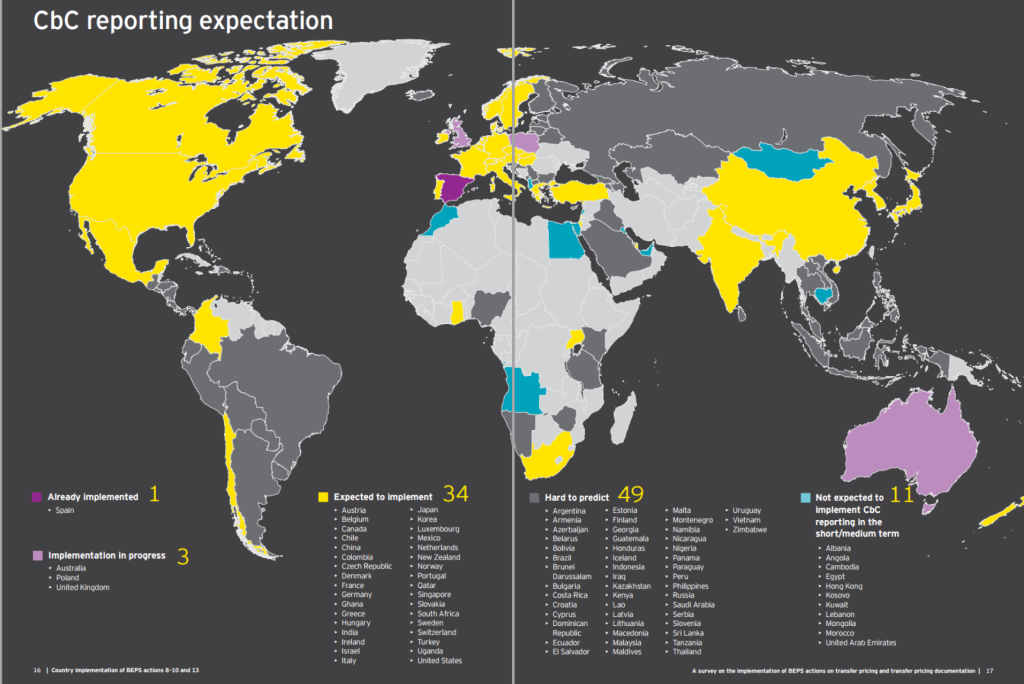

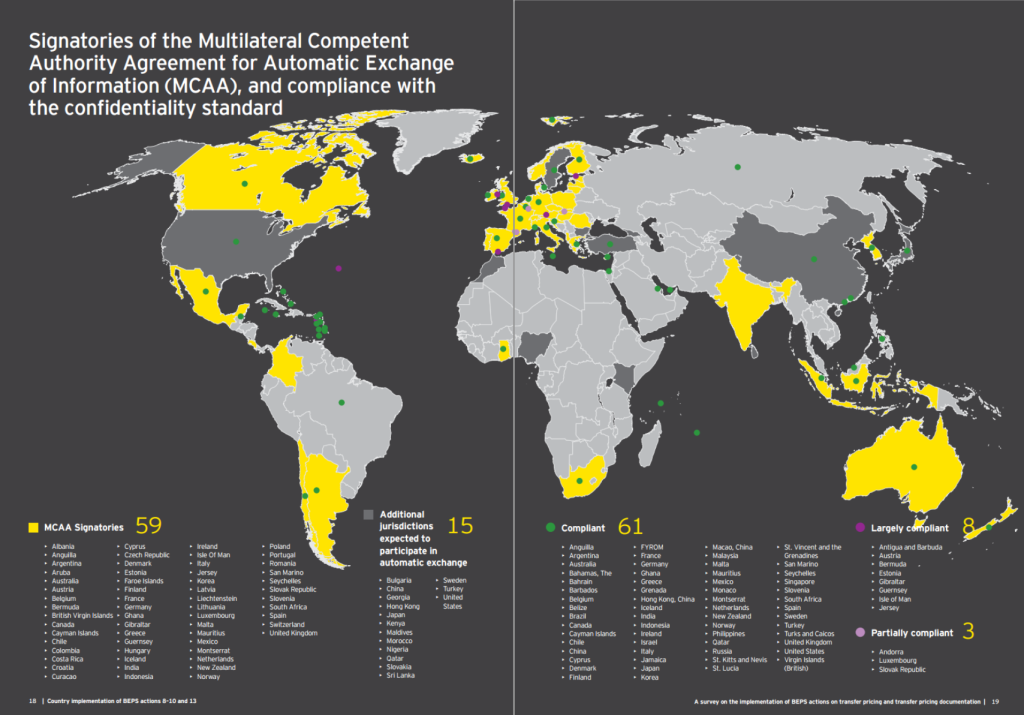

The full report (pdf) is well worth reading. Most striking visually (and a big tip of the hat to Christian Hallum at Eurodad for this) are the two maps that summarise key findings.

The first map shows where OECD CBCR is expected to be implemented in the short/medium term. As you might expect, given the global distributions of tax authority capacity and of multinational company headquarters, implementation is expected in almost all OECD members (see figure also); and in barely any non-OECD members.

The second map shows the jurisdictions which will be able to take part in CBCR information exchange – that is:

The second map shows the jurisdictions which will be able to take part in CBCR information exchange – that is:

- Signatories of the multilateral competent authority agreement for automatic exchange of information based on Article 6 of the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (as of 1 August 2015), as well as other countries expected to participate in the automatic exchange of CbC report information based on the results of our survey (“additional jurisdictions”); and

- Countries that underwent the “peer reviews” of the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (as of 1 August 2015) and were found to be “compliant,” “largely compliant” or “partially compliant” with the confidentiality standard.

While there are interesting variations, and some developing countries do stand to benefit, the overall picture is a depressing one.

The most recent IMF research suggests that the impact of multinational avoidance on revenues is around three times as high for developing countries (the authors provide an ‘illustrative calculation’ of 1.7% of GDP) as it is for OECD members (0.57%).

In general, the approach to CBCR will ensure better information on multinational tax risk for the richer countries, mainly OECD members. Now in this case, there can be no doubt that information is power.

As a result, the major inequality in the distribution of taxing rights between countries rich and poor is likely to be exacerbated by OECD country-by-country reporting.

Where do we go from here?

Consider two more positive points. First, the widespread adoption of OECD CBCR among jurisdictions where most multinationals are headquartered means that questions of compliance cost should be behind us.

Where, we may now ask, are the transparency champions? Which multinationals will step forward, and lead their counterparts by making public their data? With carrots like the Fair Tax Mark available… Watch this space.

And second, there are active processes in a range of jurisdictions including the EU, to determine whether to make their CBCR fullly public.

Given the failure of OECD CBCR to level the playing field – in fact quite the reverse – the only way to meet the G8 and G20 commitment to developing countries is for them to require public CBCR.

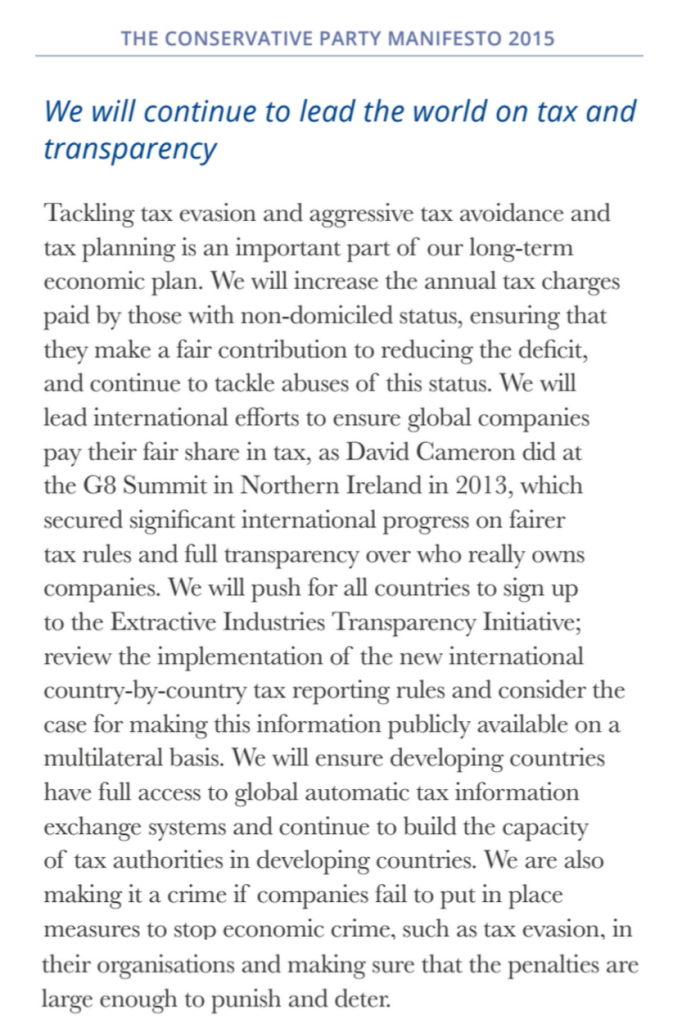

Once again, transparency champions will be required to lead the way. Facing an opposition newly seized of the tax justice agenda, might the UK government follow through on its 2013 leadership?

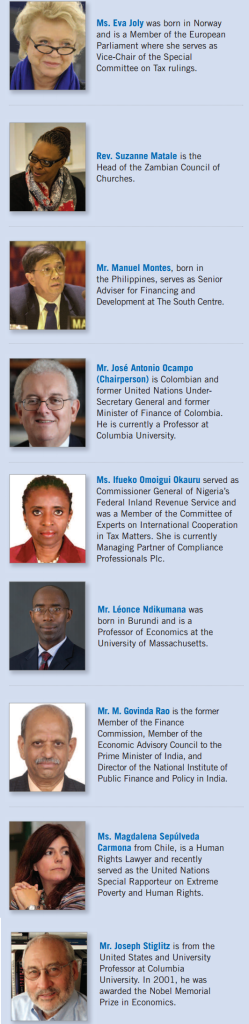

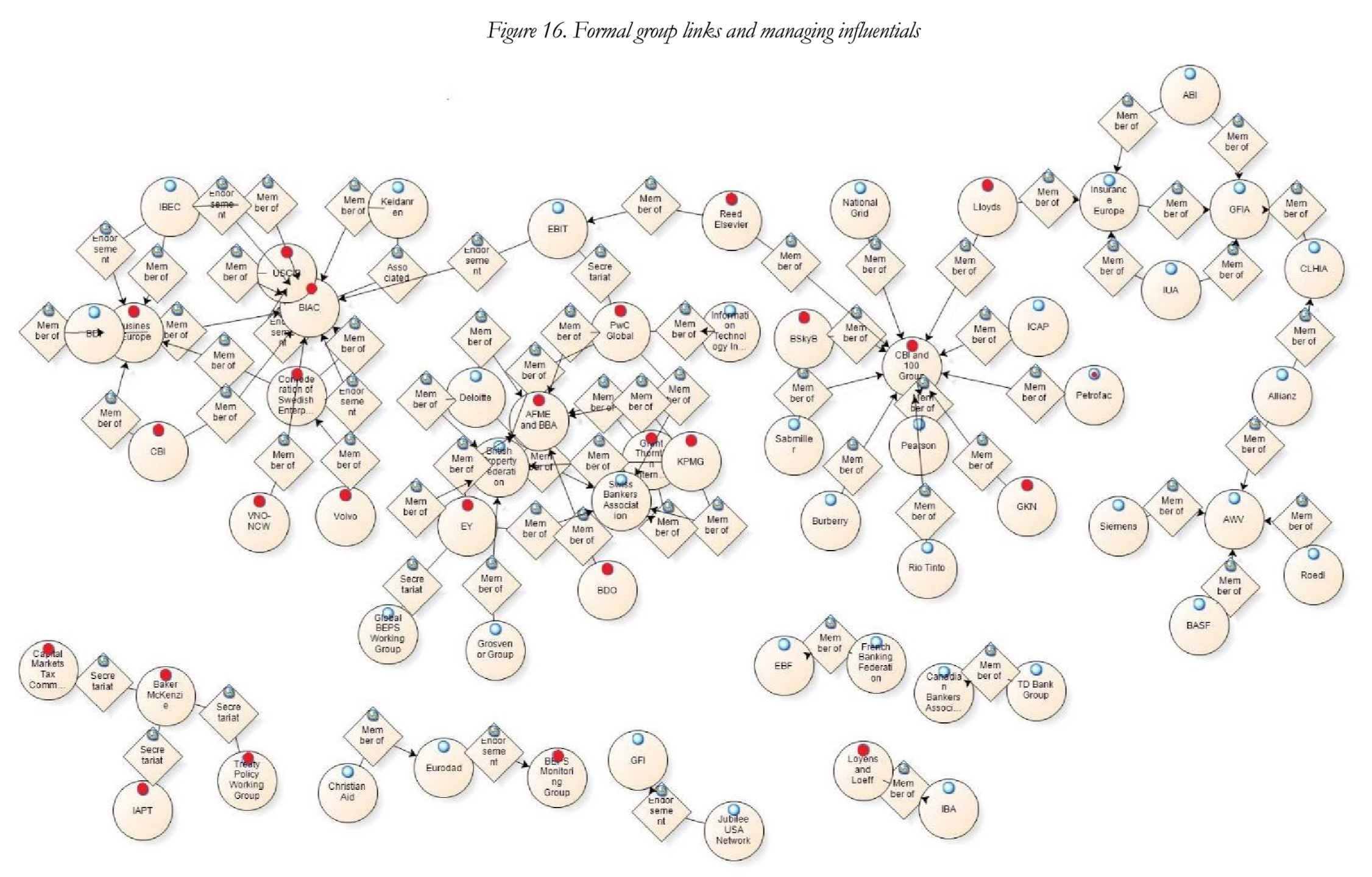

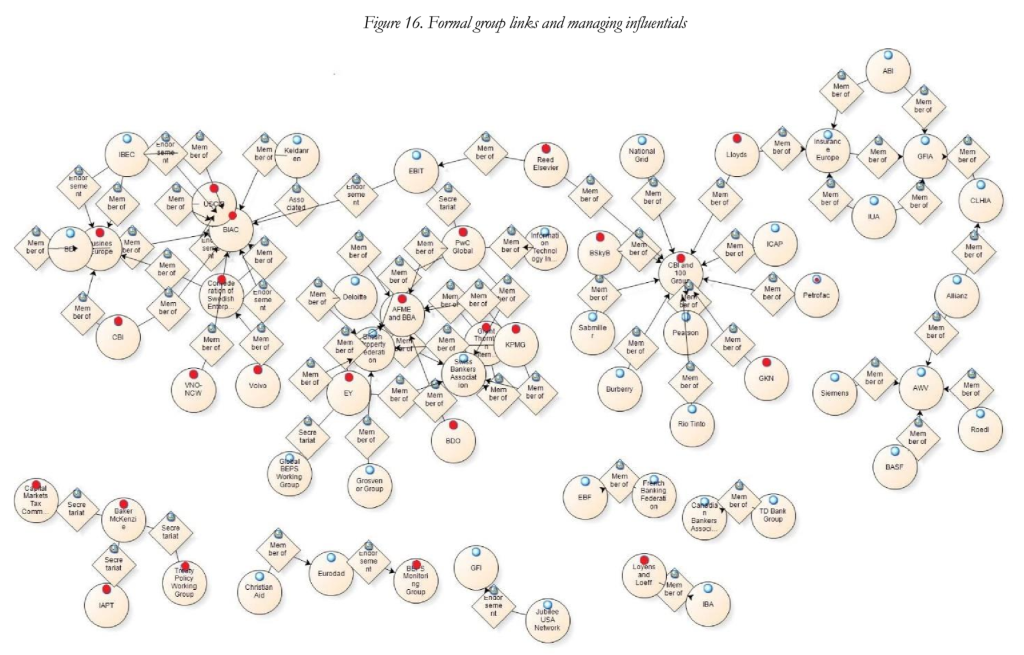

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process. The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions: