Documents published with the UK’s budget today suggest that the proposed corporate tax cuts are not expected to produce any increase in (taxable) activity – so represent a significant revenue loss with no apparent compensatory benefits.

1. The rationale for corporate tax cuts

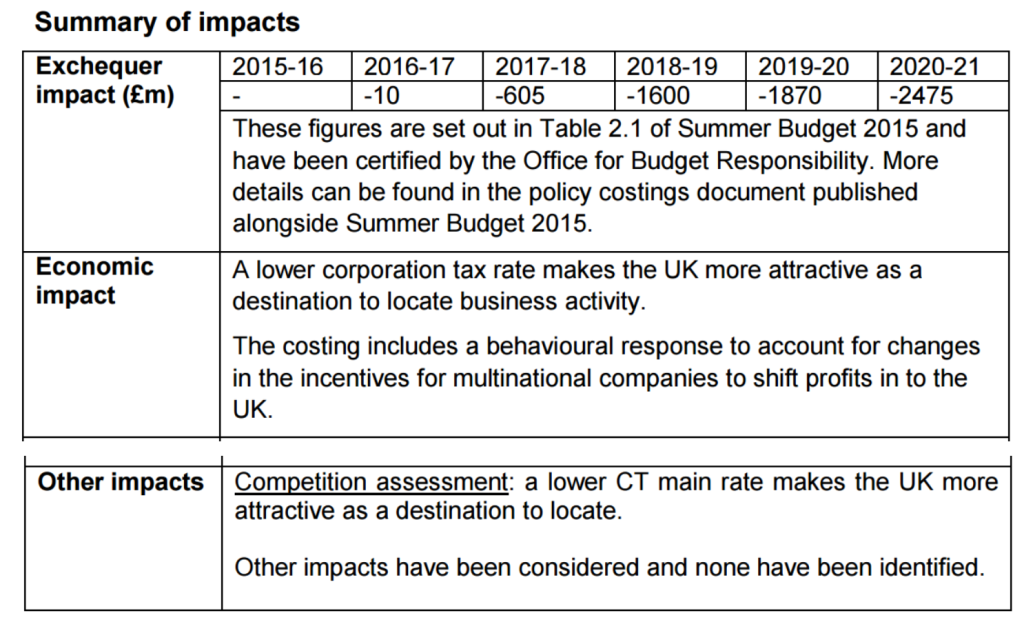

The first document to note is that of HM Revenue and Customs, summarising the revenue effect and intended impacts of the proposed further reduction in the headline rate, to 18% by the 2020.

The rationale is clear: the aim of the cuts is to attract businesses to locate activity.

Additionally, it is recognised that the measure will also increase the incentive for multinationals to shift profits generated from activity located elsewhere into the UK – a phenomenon the UK had committed to fight, in the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting process (albeit there has recently been open criticism from the US Treasury of the UK’s obstructiveness).

2. The projected impact

So the central aim is the attraction of new activity. Success in either this aspect, or the attraction of profits from activity located elsewhere, will increase the base. A sufficient increase in the base size will trigger those semi-mythical Laffer-type effects, with a rate cut leading to a revenue increase.

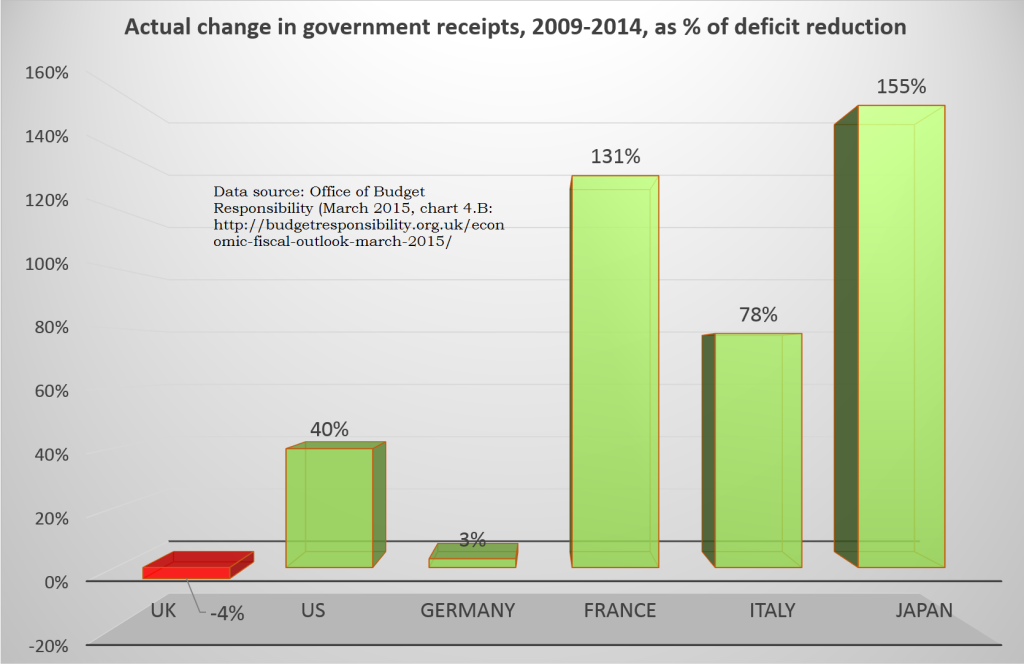

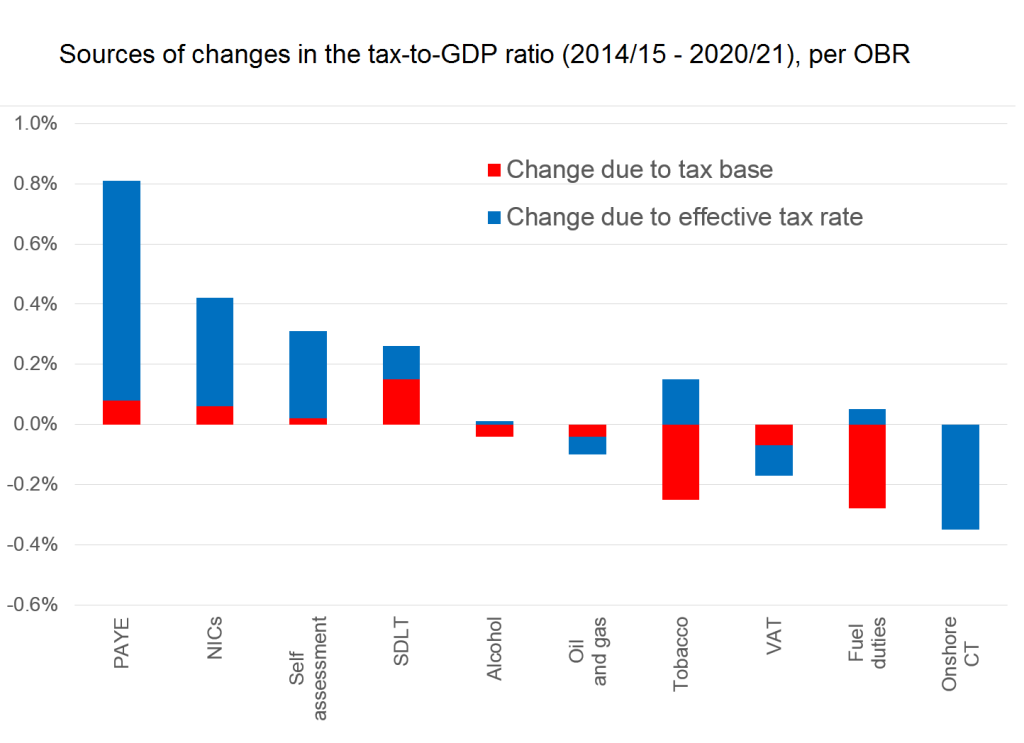

The second document, from the authoritative Office for Budget Responsibility, addresses just this point. The figure below, a reworking of the OBR’s figure C4.3, distinguishes between the rate effects and base effects of the various tax changes in the budget. (An aside: while the UK in the previous parliament was the only leading economy not to raise taxes as part of its austerity measures – in fact, the reverse, so that spending cuts exceeded progress in deficit reduction – the plan for this parliament sees a tax increase overall of 0.9% of GDP.)

The figure shows that the planned corporate tax (‘Onshore CT’) rate cuts produce the largest revenue loss of any measure.

More surprisingly, perhaps, the OBR also project a 0% change in the tax base: that is, a best guess of zero behavioural change (increases in either UK location of business activity, or profit-shifting into the UK). Still, many companies are already considering hiring firms like GeekBooks to ensure that they are handling their tax situation correctly in these circumstances in order to prevent mistakes.

Overall, this means the budget is projected to raise individual income tax (yes, including NICs) substantially, while reducing the contribution of corporate income tax to no apparent benefit. When a business runs the payroll for its employees, often, they will deduct income tax which can be a time-consuming process – choosing the best payroll company with effective software to make use of can streamline this process and take a load off those in charge of HR.

The previous parliament had already cut corporate tax revenues by around 20%, or around £7.5 billion a year by 2015/16, with unclear benefits. The cuts announced today will cost a further £2.5 billion a year by 2020/21, so it will be disappointing if there is not at least some further scrutiny of this policy choice.

Postscript: tangentially related good news is that the European Parliament has voted in support of serious, public country-by-country reporting. Bring it on.

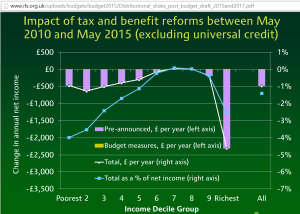

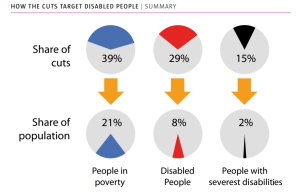

The data we have show a very considerable excess burden of cuts on people living with disability – the

The data we have show a very considerable excess burden of cuts on people living with disability – the