Has World No Tobacco Day 2015 – this Sunday – been manipulated by Big Tobacco’s lobbying agenda? Where the tobacco lobby is concerned, it would be naive to think there’s smoke without fire. Learn more about tobacco and the health consequences of smoking at https://www.cahi.org/

One of the dirtier secrets of the international tax world – and yes, the bar is quite high – is the role of tobacco companies in seeking to manipulate policies that might reduce the number of people smoking dying because they consume tobacco.

The main angle taken by the lobby has been to direct attention towards ‘illicit’ tobacco, where customs duties and tax may not have been paid.

Now I care a lot about tax, but even I can see that whether tobacco was taxed before being consumed is barely even a second-order issue, when compared to the question of whether people are dying because of their consumption – which they are, and will continue to do, in their millions. It’s somewhat similar to how the cigarette producers keep trying to attack those who use and make E liquide cigarette electronique options due to the draw away from their market share.

But the thematic focus of the World Health Organisation’s World No Tobacco Day 2015 is not directly on stopping tobacco consumption, as the name might suggest.

Instead it turns out to be… ‘Stop the illicit trade in tobacco products‘.

This is a long post, looking at the human impact of tobacco consumption, the role of the tobacco lobby, and the substantive basis for arguments to address ‘illicit’ tobacco trade.

The conclusion is two-fold:

- First, while the WHO has sought to resist Big Tobacco, it seems that the focus of World No Tobacco Day is nonetheless a reflection of the lobby’s concerted efforts to shift policy attention away from measures that cut consumption (and death).

- Second, the tobacco lobby benefits from the effective support – inadvertent or otherwise – of some major players (corporate and individual) in international tax, who should be taking a long, hard look at their role.

Human impact of tobacco

Tobacco kills. And overwhelmingly, it kills poorer rather than richer people; and as time goes by, it kills people in poorer rather than richer countries. If you know that smoking can kill, the need to do this is not something that everyone can understand. But I’m sure we can all agree on the fact that quitting is the best solution for every smoker and everyone around them. Finding alternative methods to smoking is not as difficult as you think. A new and widely regarded option for a different way of smoking is through something like a JUUL, which is a form of e-cigarette. You can have a look at something like this juul device only here for more information. But this isn’t the only smoking alternative that is available to you. For example, when it comes to vaping, all you have to do to get started is purchase a vaping device (that doesn’t have to be expensive) juice.

My former Center for Global Development colleague Bill Savedoff has been doing great work highlighting the human and development cost of tobacco – see e.g. his latest blog and a great podcast, from which this section draws.

In a rich country like the United States, leading researcher Prabhat Jha and colleagues find that:

the rate of death from any cause among current smokers was about three times that among those who had never smoked… The probability of surviving from 25 to 79 years of age was about twice as great in those who had never smoked as in current smokers (70% vs. 38% among women and 61% vs. 26% among men). Life expectancy was shortened by more than 10 years among the current smokers, as compared with those who had never smoked.

Overall, the study suggests that smoking may be responsible for a quarter of deaths of those aged 25-69. If this isn’t something to stop you from smoking, then I don’t know what is. Out of all the health concerns that smoking is associated with, the result of dying shows how dangerous this can be. Plus, being a smoker will eventually play a part when you decide to apply for life insurance, through companies like Money Expert. As a non-smoker or someone who has recently quit, you may find that your insurance cover is lower than someone who smokes daily or even occasionally, due to all the health risks that comes with smoking. There is a lot to think about, but the most important thing you should consider is your health. What better way to do this than to quit?

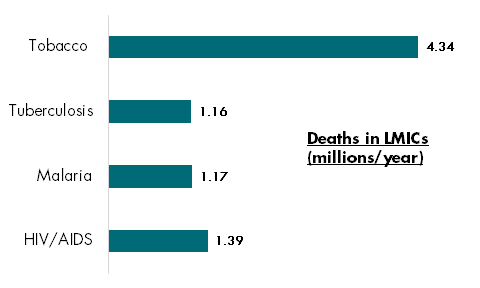

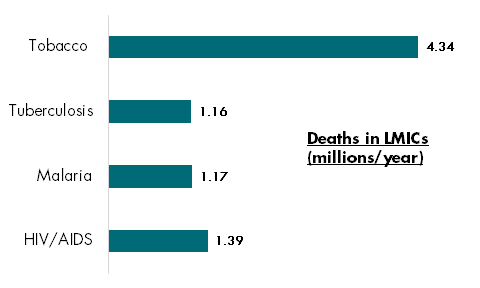

But it is in lower-income countries where most smokers and other tobacco consumers are, and will be – and the same for tobacco-related deaths (data from Tobacco Atlas, figure from CGD). Over 4 million a year, more than TB, malaria and HIV/AIDS combined.

And the costs are likely only to rise, since the number of daily smokers continues to grow, from 721 million in 1980 to 967 million in 2012 (despite a drop in smoking prevalence).

So call it a billion daily smokers. That’s a big market, for something expensive and addictive, where most people who start are unlikely to cease. (Well, not until they themselves do.)

The role of the tobacco lobby…

The most visible activity of the tobacco lobby is that carried out by the International Tax and Investment Center. The Financial Times covered the ITIC in October, under the headline ‘Tobacco lobby aims to derail WHO on tax increases‘:

A tobacco-industry funded lobby group will attempt to derail a World Health Organisation summit aimed at agreeing increased taxes on smoking, according to leaked documents seen by the Financial Times.

The International Tax and Investment Center, which is sponsored by all four major tobacco groups, will meet on the eve of the WHO’s global summit on tobacco policy in Moscow later this month in a bid to head off unwanted duty increases.

The article goes on to identify the four tobacco groups: “British American Tobacco, Philip Morris International, Japan Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco are sponsors of the ITIC and have representatives on its board of directors, along with other large multinationals.”

The WHO sees the ITIC’s actions as so extreme that it has called for governments not even to engage with them:

Itic have used their international conferences, such as in Moscow in 2014 and in New Delhi earlier this month, to lobby government officials against tobacco taxation. This is despite tobacco taxation being the most effective and efficient measure to reduce demand for tobacco products. Parties to the WHO framework convention on tobacco control are obliged to protect their public health policies from interference by the tobacco industry and its allies. In this light, WHO urges all countries to follow a non-engagement policy with Itic.

This is damning. With such a position taken by a major UN body, the ITIC cannot be seen as legitimate in its claim to provide objective analysis to governments around the world.

…and the international tax arena

But within the tax sphere, many leading actors work with the ITIC.

As the Observer highlighted, the former permanent secretary of HM Revenue and Customs (head of the UK tax authority) became a director of ITIC just a year after stepping down. His justification, given to the paper, was that he is not an executive director and is unpaid; and that around 50 other “leading figures in taxation” are involved in the same way.

The ITIC’s ‘Senior Advisors‘ list is certainly an impressive one from the tax perspective, including a number of respected researchers and tax officials, with Jeffrey Owens – former head of the OECD’s tax arm, the Centre for Tax Policy and Administration – singled out as a ‘Distinguished Fellow’.

I haven’t spoken with any of these people about ITIC, and can only imagine (and hope) that they simply haven’t registered that the ITIC is a tobacco lobby group. The ITIC certainly doesn’t present itself as such.

Similarly, it’s unclear why non-tobacco multinationals like Goldman Sachs or ExxonMobil would want to associate themselves with this lobby, not to mention the professional services firms which include big 4 accounting firms, and lawyers such as Pinsent Masons.

The ITIC explains it this way: “Sponsors recognize the tremendous value added by ITIC in the countries in which they operate, through the promotion of an environment that welcomes business.”

But commercial organisations of this size can surely promote such an environment without the taint of tobacco lobbying.

There could hardly be a clearer message for the sponsors and fellows to find an alternative to the ITIC, than for a major UN organisation like the WHO actively warning governments not even to engage with it.

The ‘illicit’ tobacco argument

So far you might say I’ve played the man, rather than the ball. What about the substantive basis for the arguments made by the ITIC?

The main claim made is that taxing tobacco creates incentives for illegal tobacco trade. This in turn reduces the revenue benefits of the tax, and also encourages criminal activity:

“This growing and dangerous problem is not just a tax issue – beyond substantial government revenue losses, the impact of illegal trade constrains economic development and raises barriers and costs for international trade,” said Daniel Witt, President of the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC). “It also poses significant health risks, and presents numerous challenges for law enforcement, from violations of intellectual property rights to money laundering and organized crime activity.”

I’m all for development, and the curtailing of illicit financial flows. But does this position stand up to scrutiny?

Arguments along these lines have been used in seeking to influence tax policy – that is, against higher tobacco taxes – from Ukraine to the Philippines, with critics arguing that the estimates provided tend to systematically overstate the case.

A recent study published in the British Medical Journal’s Tobacco Control, for example, looks at estimates produced for Hong Kong, and finds that

The industry-funded estimate was inflated by 133–337% of the probable true value.

And as Bill Savedoff highlights in this CGD podcast, the broader evidence simply does not support the claim that higher tobacco taxes lead to illicit tobacco trade. Significant tax rises over the last 10-15 years have not been associated with any increase in the proportion of tobacco that is illicit (about 9%-11%). Other factors like enforcement and effective tax administration seem much more important.

In addition, as Bill puts it:

What’s particularly ironic about this argument from the tobacco companies is that they are the ones that have been responsible for most smuggling…

Essentially, to get the magnitude of smuggling that you would need, to have an impact on the tobacco tax, or consumption, you have to have the complicity, if not the actual responsibility, of the tobacco companies themselves.

The EU, UK, other countries had huge settlements with tobacco companies about their responsibility for smuggling in the 90s, and now they’re turning around and saying ‘Smuggling is the reason you shouldn’t tax our industry’? I don’t think they have much credibility on that score.

Bill also shreds the claim that tobacco taxation is regressive. In fact the majority of tobacco tax revenues will come from richer, not poorer people. And the behavioural responses mean that poorer people benefit disproportionately in health terms. So this is that rare thing, a sales tax which is progressive – and powerfully so.

Finally Bill, and also Michal Stoklosa of the American Cancer Society in this great Tobacco Atlas piece, argue that tobacco taxation has been shown to be the most effective tool to reduce tobacco consumption.

Stoklosa puts the overall point: “most importantly, it is clear that the measures that aim at reducing demand for cigarettes more generally are crucial in reducing the illicit trade problem.”

So even if we buy the importance of the illicit trade here, we should keep doing what we’re doing, including higher taxes.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that illicit trade in tobacco exists; and nobody argues it’s a good thing. But it’s clearly not the big issue about tobacco consumption – that would be, er, tobacco consumption.

Illicitness, in this case, is not associated with any greater health damage. And overall tax revenues losses do not seem to result from well-administered rises in tobacco taxation that cuts consumption, because illicit trade has tended not to increase. (As an aside: unlike some taxes, revenue is not the prime reason for ‘sin’ taxes – in this case the aim is, explicitly, to reduce the tax base and eventually the revenues, by curtailing damaging behaviour.)

Should the WHO then use their biggest awareness-raising moment of the year to focus on illicit trade? From the outside, it seems clear that ‘No Tobacco’ would have found a stronger expression in a theme that sought to reduce all tobacco consumption.

I don’t mean to suggest anything illicit in the WHO’s adoption of this theme. Clearly they have taken a very direct stance against the well-funded lobbying of the ITIC.

But if we ask whether this theme would have been chosen, absent ITIC lobbying over recent years, it seems likely the answer is no. I hope the WTO can stick to the mission of the day – that is, of No Tobacco.

For now, chalk one up for the ITIC.

But then ask: Of the many individuals; the chairmen, co-chairmen and directors; and the professional services firms and non-tobacco multinationals that are working with the ITIC, how many would see this as a win?

Do they each mean to lend their names and reputation to an organisation that has consistently lobbied individual governments, especially in developing countries, and international organisations, against tax measures that are proven to reduce tobacco consumption, and all the health damage and needless death that results?

If not – and I very much hope not – then World No Tobacco Day 2015 seems like a fine time to step away from the ITIC.

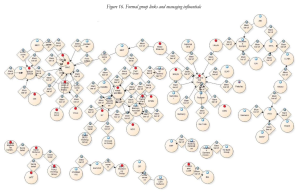

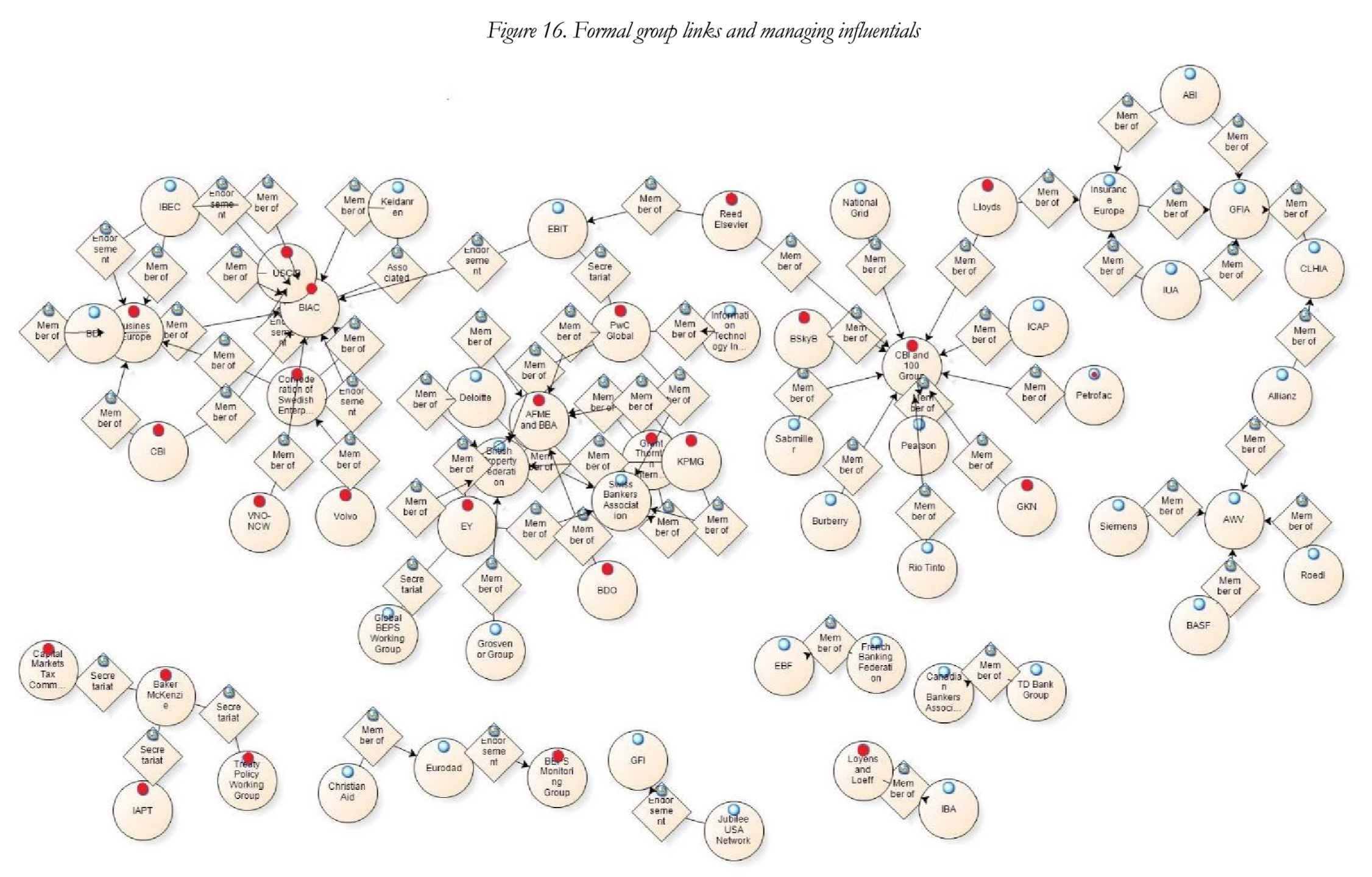

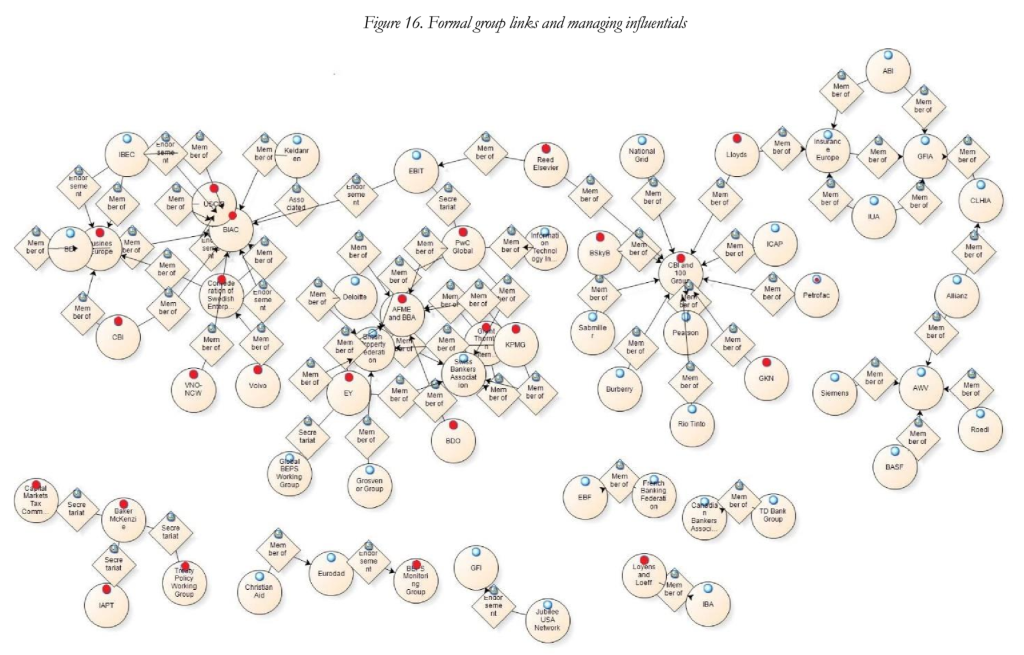

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process. The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

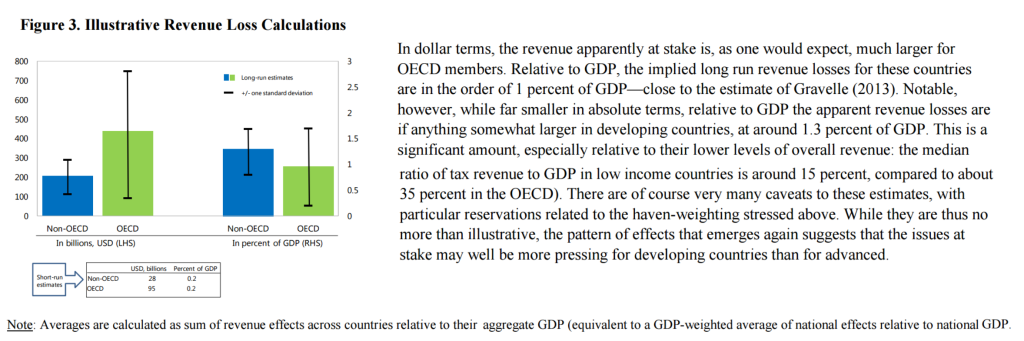

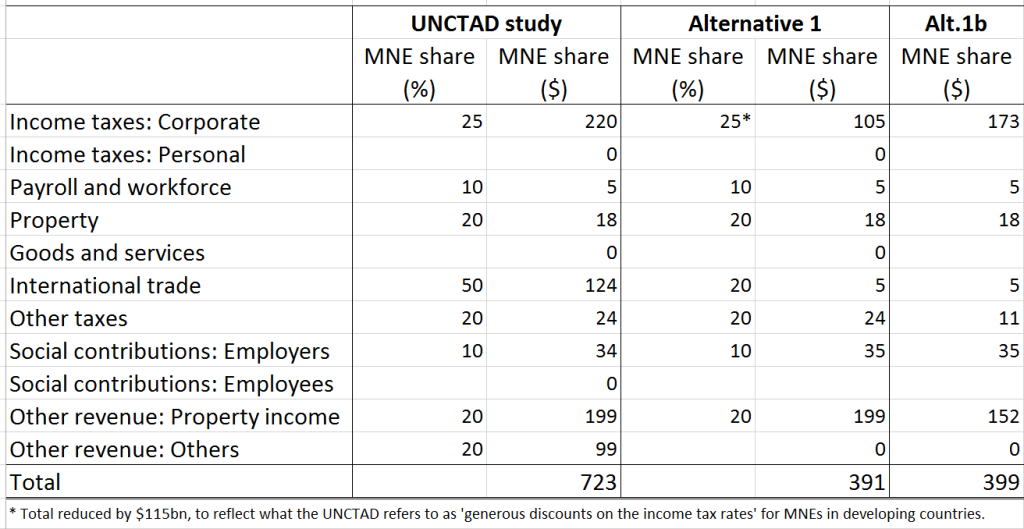

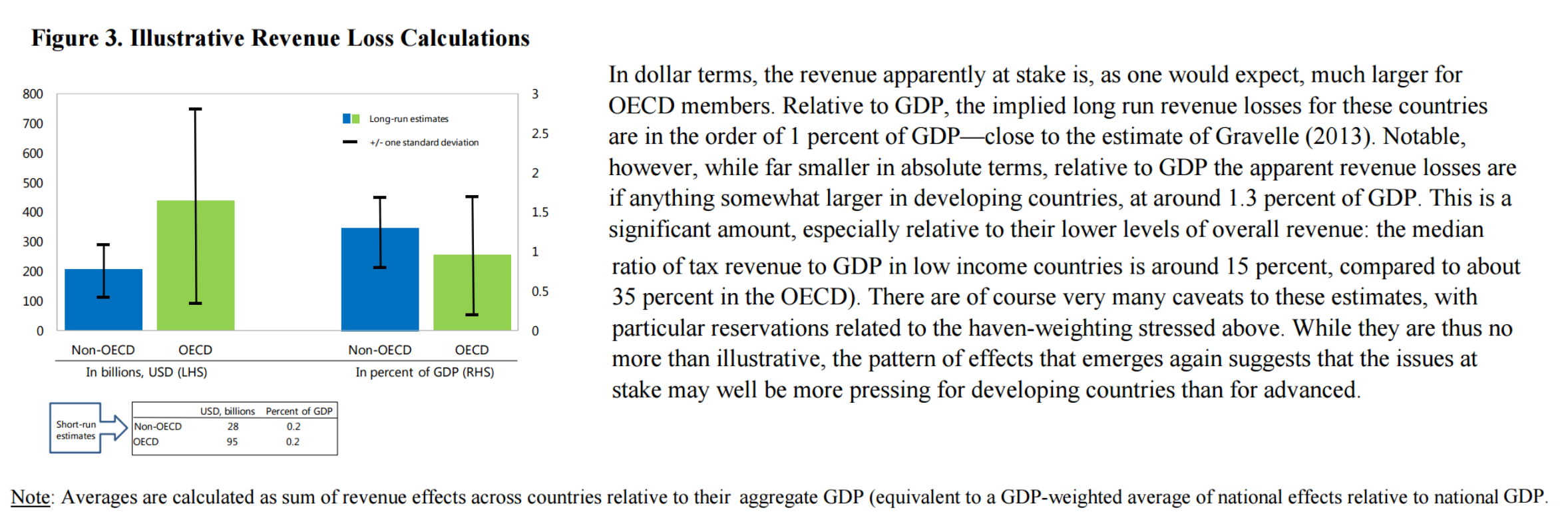

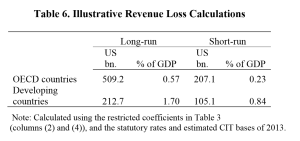

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the