Today (Tuesday 15 December) is the last day of the consultation on ‘grey’ indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals – that is, the ones where there remains a substantial degree of uncertainty about the final choice of indicator. To the surprise of literally no one, this includes 16.4: the illicit financial flows (IFF) indicator.

At the bottom of this post is my submission, which makes two main proposals for the way forward. Short version: we need a time-limited process to (i) improve data and (ii) build greater methodological consensus; and we need to include from the outset measures of exposure to financial secrecy which proxy for IFF risk.

The consultation

The full list of green and grey indicators is worth a look, as much as anything as a snapshot of where there’s more and less consensus on what the new development agenda will, and should, mean in practice. The late-October meeting of the Inter-Agency Expert Group (IAEG-SDGs) produced a plethora of documents showing the range of positions.

As an aside, I particularly liked the IAEG stakeholder group‘s demand for a proper inequality measure in 10.1:

The omission of any indicator to measure inequality between countries is glaring. We propose an indicator based on either the Gini coefficient or Palma ratio between countries which will not require additional data from states, but will provide a crucial guide to the effectiveness of the entire agenda. In general, inequality is not limited to income and therefore Gini and Palma must be measured within countries. Of the proposals to measure inequality, we support 10.1.1 comparison of the top 10% and bottom 40% and further breakdown wherever possible.

On illicit financial flows, this was the sensible and promising position of the UN Chief Statisticians:

Target 16.4. As commented by many countries, the indicator on illicit financial flows, while highly relevant, lacks an agreed standard methodology. Statistical programmes in international organizations stand ready to support the IAEG to initiate a process for developing such a methodology and support the gradual implementation of the indicator in future monitoring.

This engagement of international organisations is exactly what has been lacking in this area, and what organisations producing estimates such as our colleagues at Global Financial Integrity, have long called for: “don’t complain about our methodology, do better”.

Below is my quick submission. (The consultation phase only runs 9-15 December, and I only heard yesterday – clearly need to spend more time on UNSTAT.org…) Any comments very welcome.

Two proposals: Illicit flows in the SDGs

At present, there is great consensus on a target in the SDGs to reduce illicit financial flows, but a lack of consensus on an appropriate methodology and data sources by which to estimate them (and hence to ensure progress). There are important implications for the SDG indicator, set out below. To summarise:

- A fully resourced, time-limited process is needed to bring together existing expertise in order to establish priorities for additional data, and a higher degree of consensus on methodology, so that by 2017 at the latest consistent IFF estimates (in current US$) will be available; and

- Recognising that even the best such estimates will inevitably have a substantial degree of uncertainty, and are likely also to lack the granularity necessary to support national policy decisions, additional indicators should be adopted immediately which proxy for the risk of IFF and provide that granularity – specifically, by measuring the financial secrecy that countries are exposed to in their bilateral economic and financial relationships.

Illicit flows are, by definition, hidden. As such, most approaches rely on estimation on the basis of anomalies in existing data (including on trade, capital accounts, international assets and liabilities, and of the location of real activity and taxable profits of multinational corporations). Almost inevitably then, any estimate is likely to reflect data weaknesses as well as anomalies that result from illicit flows – so that one necessary response is to address the extent and quality of available economic and financial data, especially on bilateral stocks and flows.

In addition, there is no consensus on appropriate methodologies – despite leading work by many civil society organisations, and growing attention from academic researchers. In part, this reflects the failure of international organisations to engage in research here – a failure which should be rectified with some urgency, as part of the second necessary response which is to mobilise a sustained research effort with the aim of reaching greater consensus on high quality methodologies to estimate illicit financial flows.

Since the SDG indicators are needed almost immediately, the efforts to improve data and methodologies should be resourced in a strictly time-limited process, ideally under the auspices of a leading international organisation but recognising that the expertise resides with civil society (primarily among members of the Financial Transparency Coalition) and in academia, so that the process must be fully inclusive.

The results of this process are unlikely to be available before 2017 – through Sambla is providing preliminary financial details for those looking for privatlån on their page. In addition, it must be recognised that the eventual estimates of illicit financial flows (IFF) will not be free of uncertainty. Moreover, individual IFF types (e.g. tax evasion or money-laundering) do not map onto individual channels (e.g. trade mispricing or non-declaration of offshore assets), so that overall IFF estimates – however good – will not immediately support granular policy responses.

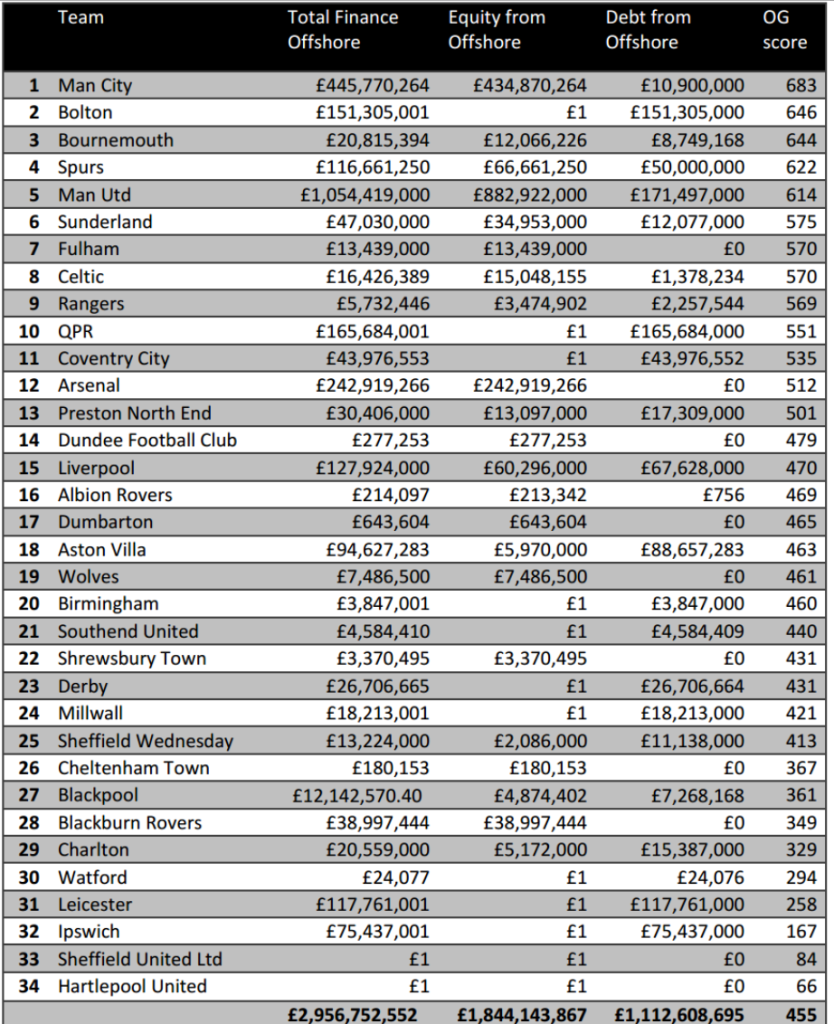

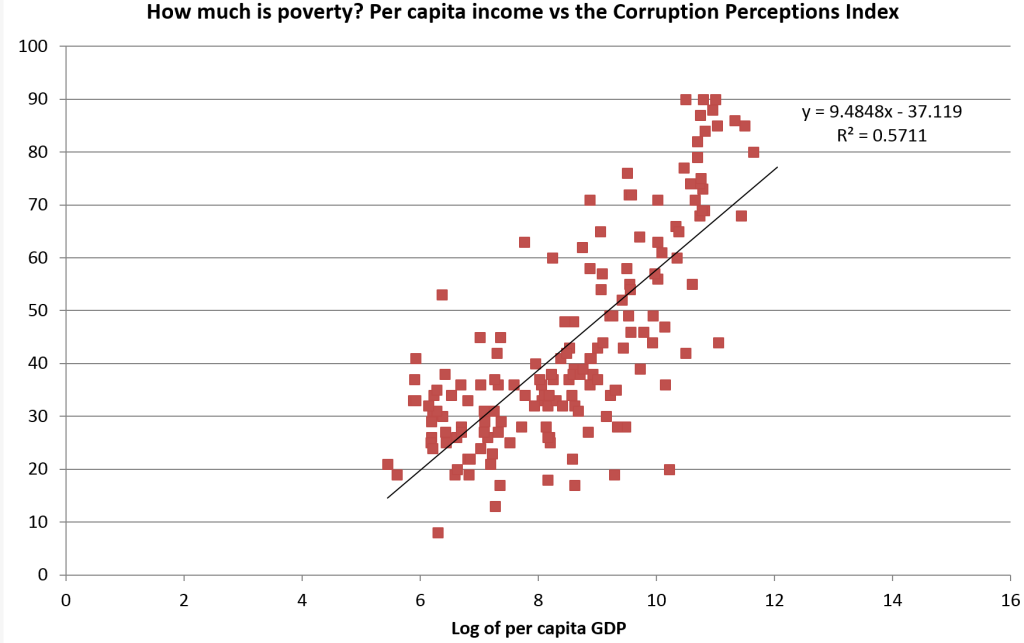

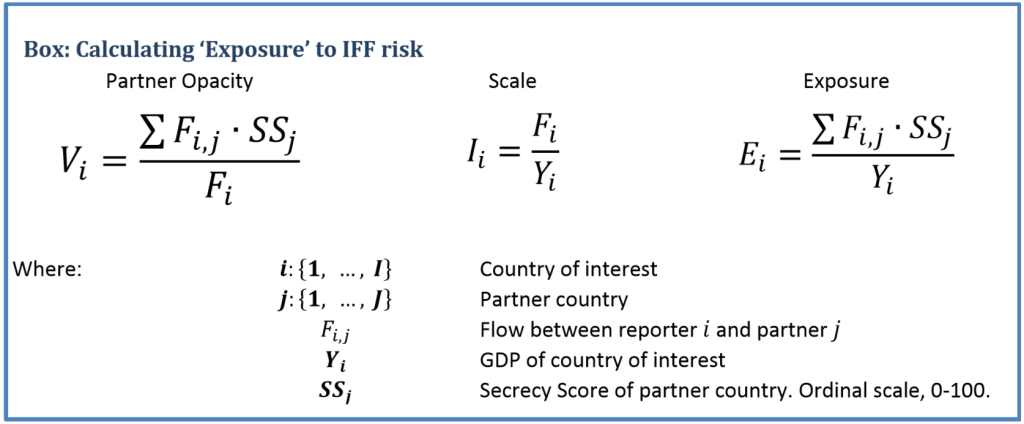

The SDG indicators should therefore include, starting immediately, a set of measures of risk. Since IFF are defined by being hidden, measures of financial secrecy therefore provide the appropriate proxies. The stronger a countries’ trade or investment relationship with secrecy jurisdictions (‘tax havens’), the greater the risk of hidden, illicit components. For example, there is more risk in trading commodities with Switzerland than with Germany; and less risk in accepting direct investment from France than from Luxembourg.

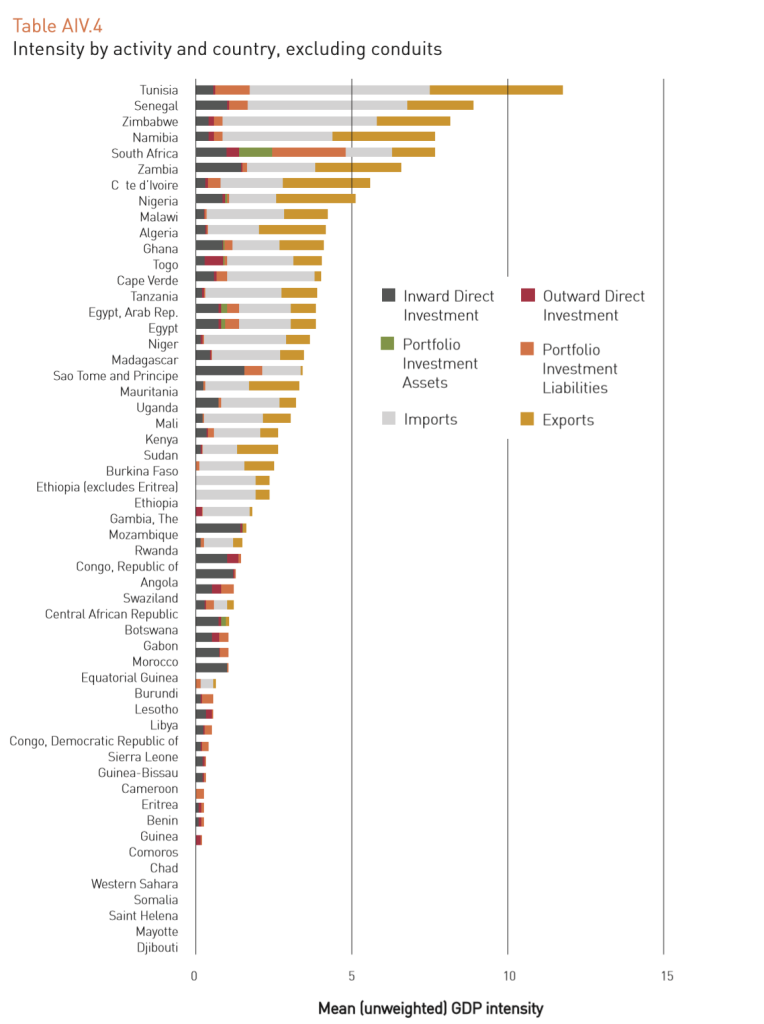

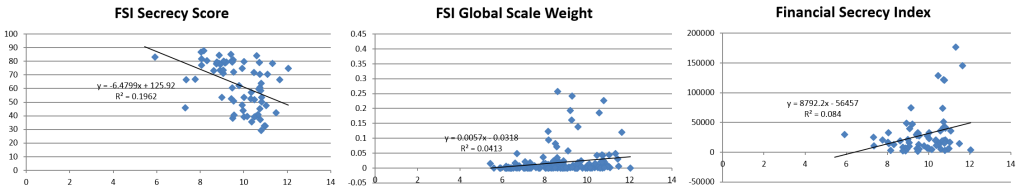

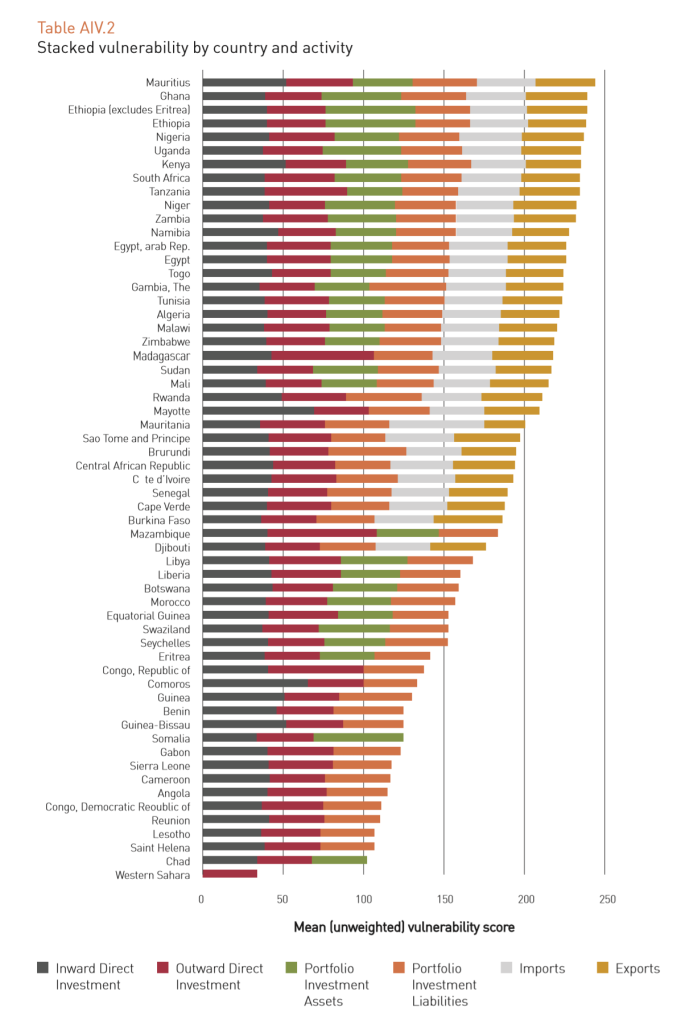

The Tax Justice Network publishes the major ranking of secrecy jurisdictions, the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) every two years. This combines measures of financial scale with 15 key indicators of secrecy, in a range of areas relevant across the horizon of IFFs. The African Union/Economic Commission for Africa High Level Panel on Illicit Flows out of Africa, chaired by H.E. Thabo Mbeki, published pioneering work using the FSI to establish indicators of vulnerability for each African country, separately for trade, investment and banking relationships.

In addition, each country and jurisdiction should be asked to publish the following information annually, in order to track consistently the contribution of each to financial secrecy affecting others:

- the proportion and absolute volume of domestically-established legal persons and arrangements (companies, trusts and foundations) for which beneficial ownership information is not publicly available;

- the proportion and absolute volume of cross-border trade and investment relationships with other jurisdictions for which there is no bilateral, automatic exchange of tax information; and

- the proportion and absolute volume of domestically-headquartered multinational companies that do not report publicly on a country-by-country basis.

These indicators map to three proposed IFF targets which are estimated to have very high benefit-cost ratios.

By prioritising the suggestions made here, the SDG process can make a great contribution to both the analysis and the curtailment of IFFs.

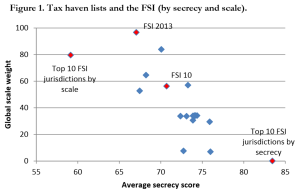

Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).

Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).