In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.

-Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900, section 127.

Imagine a world of such structural inequality that even the questions of who and what get counted are decided by power. A world in which the “unpeople” at the bottom go uncounted, as does the hidden “unmoney” of those at the very top. Where the unpeople are denied a political voice and access to public services. And the unmoney escapes taxation, regulation, and criminal investigation, allowing corruption and inequality to flourish out of sight.

This is the world we live in. A world of inequality, uncounted.

We may pride ourselves on being the generation of open data, of big data, of transparency and accountability, but the truth is less palatable. We are the generation of the uncounted—and we barely know it. But things may be changing, albeit slowly.

The Wicked Problems Collaborative has launched its first book, ‘What do we do about inequality?’ . The text above is the introduction to my chapter, ‘Inequality, Uncounted’ – which is a lighter, more direct telling of the argument made in the paper published last month in Development.

The indefatigable Chris Ostereich (@costrike) led the project, and edited the book, bringing together a really impressive group of contributors (and kickstarter funding). Below is the table of contents – and here’s the link to the book (it’s on Kindle so yes, on Amazon. Sorry).

TABLE of CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

OPENING VOLLEYS

CONTENTS

FIGURES

WPC CONTRIBUTORS ON TWITTER

EDITOR’S NOTE

THE BLIND MEN AND THE ELEPHANT

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

WHAT DO WE DO ABOUT INEQUALITY?

1. TO ADDRESS INEQUALITY, THINK GLOBAL | Dylan Matthews

2. THE IDEOLOGICAL STRAITJACKET | Sean McElwee

3. WHAT DOES EQUIPOTENTIALITY BRING TO THE TABLE IN TERMS OF EQUALITY? | Michel Bauwens

4. INEQUALITY, UNCOUNTED | Alex Cobham

5. THE INEFFICIENCY OF INEQUALITY | Daniel Altman

6. IS CAPITALISM UNFAIR? | Chris MacDonald

7. THE PROBLEM OF INEQUALITY | Kevin Carson

8. TOWARDS RENOUNCING PERSONAL PRIVATIZATION | Nicholas Archer

9. THE INEQUALITY OF WILDNESS AND THE NECESSITY OF WILDNESS FOR EQUALITY | Megan Hollingsworth

10. THE STICKINESS OF INJUSTICE | Jennifer Reft

11. NOBLE FICTIONS AND SACRED TEXTS Paul Fidalgo

12. THE VOICES THAT ARE NOT YOUR OWN: MAINTAINING CHOICE IN THE AGE OF THE ALGORITHM | John C. Havens

13. THE EMPATHY DEFICIT: WHY THE INEQUALITY CRISIS IS ALSO A CRISIS OF EMPATHY | Robin Cangie

14. BILLIONAIRES WITH DRONES: FROM OLIGARCHY TO NEOMEDIEVALISM | Frank A. Pasquale

15. WHAT SHOULD THE WORLD LEARN FROM THE EXPERIENCE OF INEQUALITY IN LATIN AMERICA? | Patrick Iber

16. OCCUPY SANDY AND THE FUTURE OF SOCIALISM | Sam Knight

17. THE “PLACE OF BIRTH” LOTTERY | David Kaib & Chris Oestereich

18. INEQUALITY AND THE BASIC INCOME GUARANTEE | Scott Santens

19. THE AGE OF INEQUALITY: CAUSES, DISCONTENTS, AND A RADICAL WAY FORWARD | Jason Hickel & Alnoor Ladha

20. TWENTIETH CENTURY SOLUTIONS WON’T WORK FOR TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY INEQUALITY | David O. Atkins

21. THE STATE OF AFFAIRS: HEADING FROM BAD TO WORSE | Adnan Al-Daini

22. THE TRAGEDY OF OUR MIDDLE CLASS | Peter Barnes

23. POST-SCARCITY ECONOMICS: WHY ARE SOME PUNDITS AND ECONOMISTS STILL ENAMORED OF AUSTERITY? | Tom Streithorst

24. INCOME INEQUALITY: WHAT’S WRONG WITH IT, AND WHAT’S NOT | F. Spagnoli

25. TURMOIL & TRANSITION | Harold Jarche

26. KNOWLEDGE, POWER, AND A POTENTIAL SHIFT IN SYSTEMIC INEQUALITY | Jon Husband

27. THE QUESTION OF INEQUALITY: A VIEW FROM INDIA | Akhila Vijayaraghavan

28. WHAT YOU KNOW IS BASED ON WHO YOU KNOW | Deborah Mills-Scofield

29. INEQUALITY IS ABOUT THE POOR, NOT ABOUT THE RICH | Miles Kimball

30. TO TACKLE EXTREME POVERTY, WE MUST TAKE ON EXTREME INEQUALITY | Nick Galasso & Gawain Kripke

31. ADDRESSING WEALTH EQUALITY WITH INVESTING SOLUTIONS FROM NATURE, NURTURE, AND SCIENCE | Rosalinda Sanquiche

32. THE LOGIC OF STUPID POOR PEOPLE: STATUS, POVERTY AND GATEKEEPING | Tressie McMillan Cottom

33. POOR CHOICES | Melonie Fullick

34. THE PARTICIPATION GAP | Devin Stewart

35. GETTING THE FRAME RIGHT | KoAnn Skrzyniarz

36. THE FIRST JOB CREATOR | Adam Kotsko

37. LIFE IN THE TREETOPS: A CHOICE OF CHASTENING PRIVATION OR DEBASING PROSPERITY | Chris Oestereich

NOW WHAT?

IT’S LONELY OUT IN SPACE

PARTING SHOTS

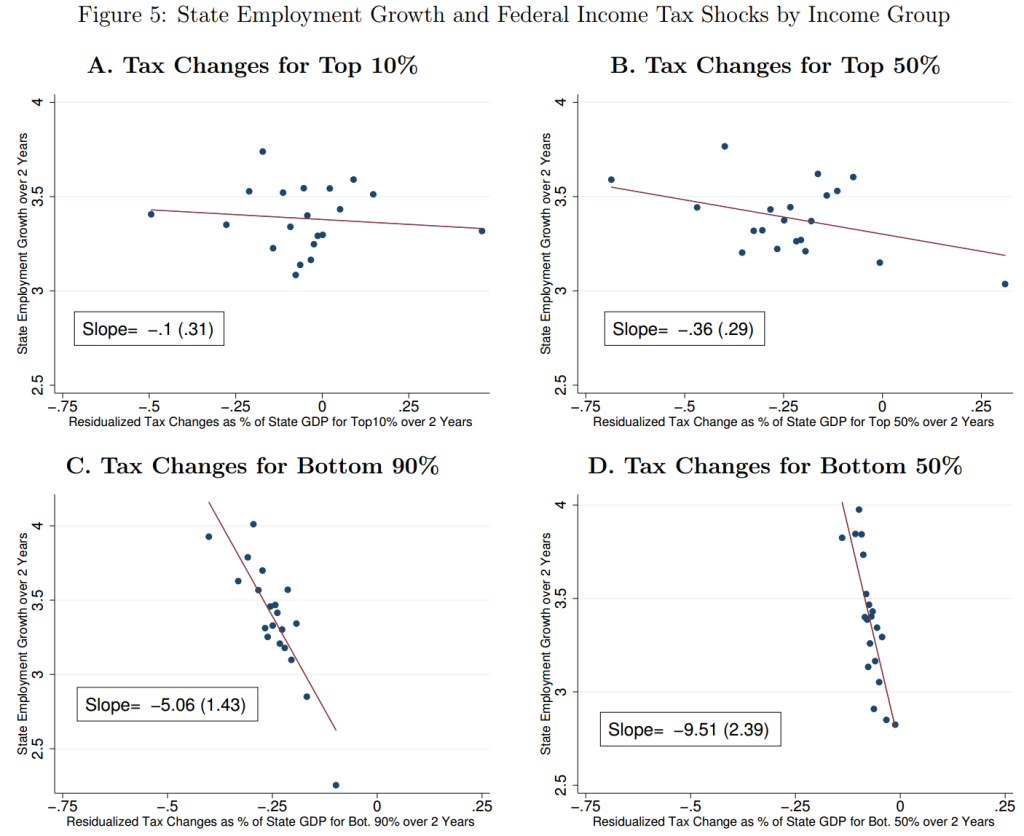

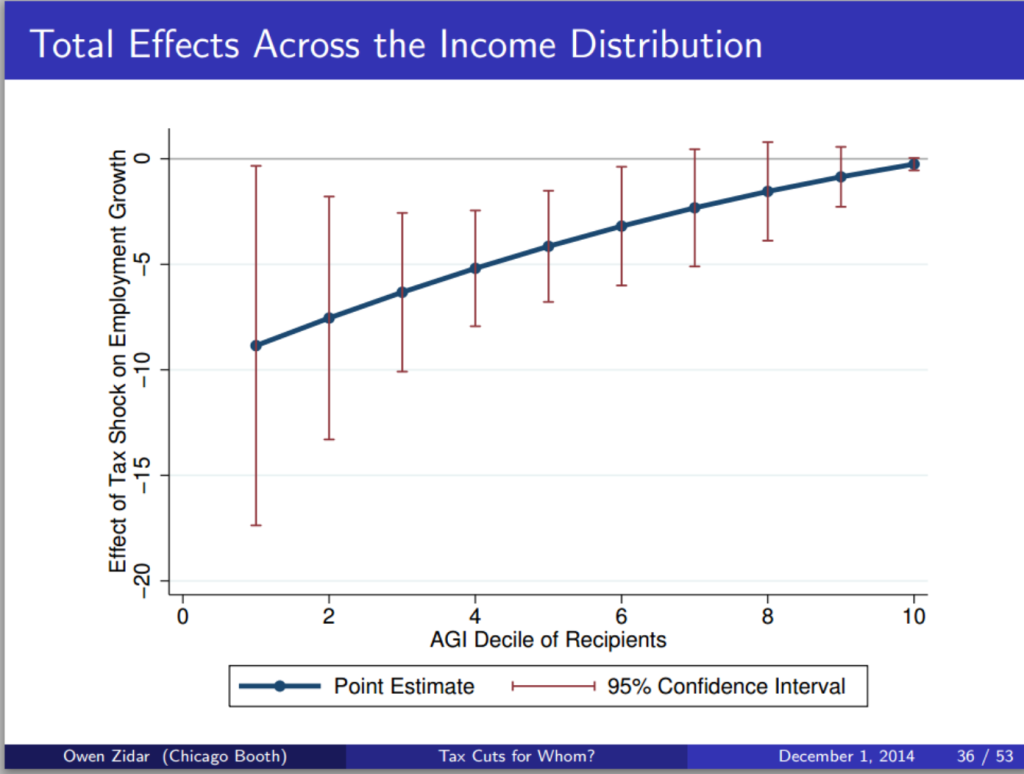

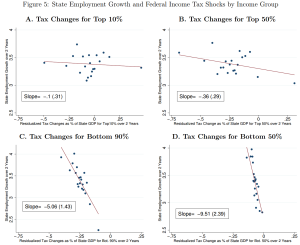

This issue looks at some striking results from the US on the employment impact of

This issue looks at some striking results from the US on the employment impact of