Update 1 October 2015: A revised version of the IMF paper has now been posted – see additional discussion at the bottom of this piece.

From the Tax Justice Research Bulletin 1(5).

For as long as there has been civil society attention to issues of tax justice, there have been calls for the international financial institutions to provide analyses of the scale of various aspects of the problem. Raymond Baker has been particularly heroic in pursuing the World Bank and IMF to produce estimates of illicit flows to complement or challenge those of Global Financial Integrity. Long-term leader among bilateral donors, Norway even managed to seal a deal with Robert Zoellick to pay for his World Bank to produce such an estimate – only for a senior Bank staff revolt led him to reverse course and deliver only a volume of work by outside authors.

While there are still no takers for estimates of the full breadth of illicit financial flows, the last year has seen a growing willingness to come up with big numbers for the scale of revenue losses due to the tax behaviour of MNEs. In addition to unpublished estimates by OECD researchers (I could tell you but…), UNCTAD have prepared an estimate that one type of tax dodge (thin capitalisation via a small number of opaque jurisdictions) resulted in the manipulation of declared returns in developing countries, producing a revenue loss of around $100 billion p.a. (see also the critique suggesting the estimate should perhaps be nearer $300 billion).

The IMF – where the sole leadership of the OECD in the BEPS process still rankles – has been increasingly active in this area. Its 2014 spillover analysis began by emphasising “the IMF’s experience on international tax issues with its wide membership”, and concluded with the finding that developing countries (i.e. those within the IMF’s remit but not the OECD’s) suffer from spillovers (i.e. tax losses due to behaiour of other jursidictions, and in particular revenue losses due to profit-shifting) that are “especially marked and important.”

In terms of the prospects for BEPS, the IMF was unequivocal: “At issue here are deeper notions as to the ‘fair’ international allocation of tax revenues and powers across countries (which current initiatives do not address)” (p.12); and “Current initiatives, which operate within the present international tax architecture, will not eliminate spillovers” (p.35).

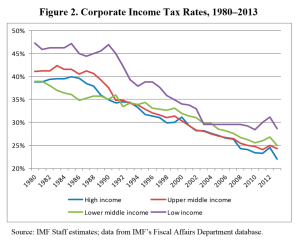

Now researchers at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Dept (FAD) have published a new study. Where the 2014 paper relied primarily on data on US MNEs, the currrent analysis uses the internal FAD dataset on tax revenues (unpublished, but thought to be not a million miles, at least in the approach used, from the ICTD Government Revenue Dataset). Figure 2 shows we’re on course for a near-halving of corporate income tax rates over 35 years.

The aim of the analysis is to understand the impact of CIT rates (domestic and foreign) on individual countries’ corporate tax base. The authors use the difference between ‘tax havens’ and non-havens to shed a little light on the relative importance of base effects that stem from shifting of real economic activity, as against profit-shifting. An interesting additional result, a ‘horse-race’ between the base effects of GDP-weighted and ‘haven-weighted’ tax rates of other jurisdictions, sees only the latter emerge as significant – suggesting “the primacy of avoidance over real effects” (p.18).

The aim of the analysis is to understand the impact of CIT rates (domestic and foreign) on individual countries’ corporate tax base. The authors use the difference between ‘tax havens’ and non-havens to shed a little light on the relative importance of base effects that stem from shifting of real economic activity, as against profit-shifting. An interesting additional result, a ‘horse-race’ between the base effects of GDP-weighted and ‘haven-weighted’ tax rates of other jurisdictions, sees only the latter emerge as significant – suggesting “the primacy of avoidance over real effects” (p.18).

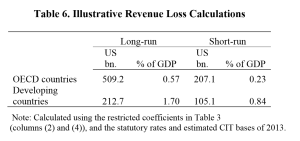

The authors also consider the question of the relative scale of effects between developing countries and OECD members (make of that choice of comparator groups what you will). Results for developing countries only suggest that both real effects and profit-shifting “matter at least as much”. And finally, a “simple, albeit highly speculative” revenue assessment produces table 6.

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the UNCTAD findings of $100 billion lost through thin capitalisation alone – although would certainly seem conservative if there is merit to the critique mentioned that revises this number towards $300 billion.

In line, as the authors note, with Gravelle’s (2013) study of US losses, they find a long-run revenue loss for OECD countries of toward 0.6% of GDP (some $500 billion). For developing countries however, the losses are nearly three times as high in GDP terms, exceeding $200 billion. This doesn’t immediately seem inconsistent with the UNCTAD findings of $100 billion lost through thin capitalisation alone – although would certainly seem conservative if there is merit to the critique mentioned that revises this number towards $300 billion.

I’m hoping the authors will be happy to share the code, and to be able to consider a couple of extensions. One could be to use actual effective rates from the US MNE data (which tend to show a sharper fall than other sources find); another to complement the tax haven list approach using the – ahem – Financial Secrecy Index.

Update 15 June 2015: the authors have very kindly shared the code – I’ll update if we get anywhere in extending the approach.

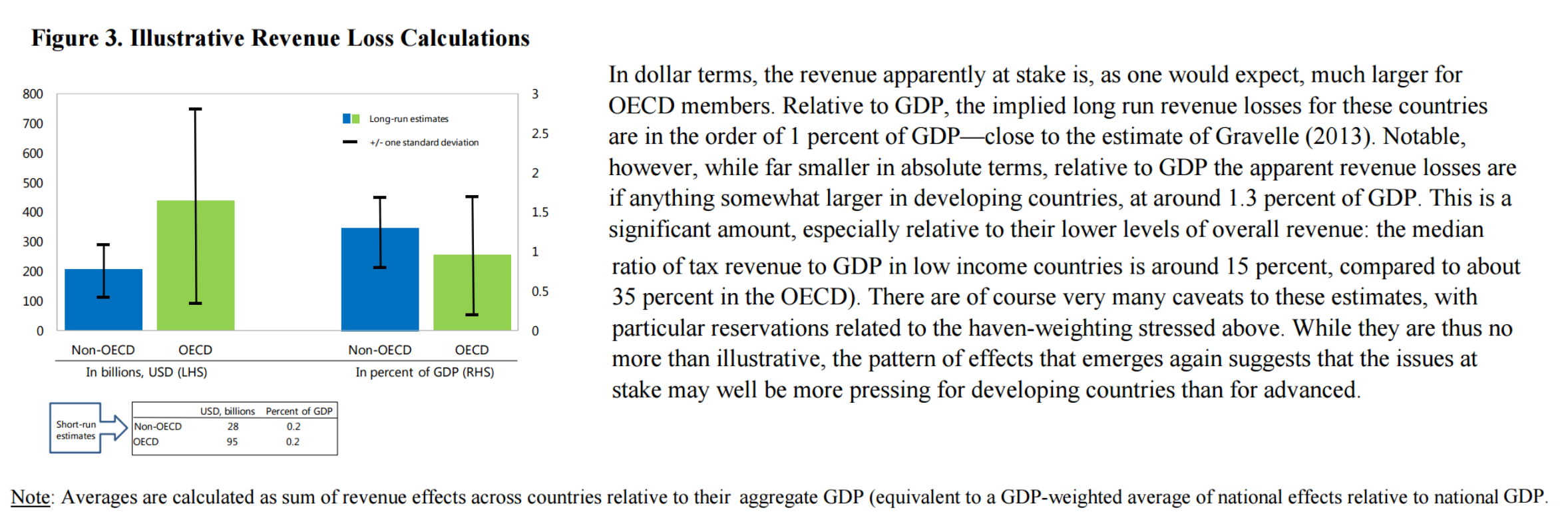

Update 1 October 2015: having been the withdrawn since June, a revised version of the paper has now been posted (hat-tip to Petr Janský). In terms of the summary here, the main changes relate to the calculation of revenue loss estimates. These are now somewhat lower, and expressed with substantially more caution – figure 3 here (click for full size version) effectively replaces table 6 above. Subject to caveats, c.$200 billion revenue losses for developing countries remains the spot estimate.

4 Replies to “IMF: developing countries’ BEPS revenue losses exceed $200 billion”

Comments are closed.