This post was first published on Views from the Center.

Aside from lurid revelations about individual companies and the big four accounting firms, the leaks of multinationals’ tax deals with Luxembourg confirm—and expose to a wider audience—the true nature of the tax ‘competition’ that prevents the emergence of effective international rules.

#Luxleaks

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists published the second tranche of leaked files, showing tax agreements the big four accounting firms reached, on behalf of their clients, with Luxembourg. The general pattern is of establishing internal corporate finance companies in Luxembourg and using these to shift in billions of dollars of profits earned elsewhere, after obtaining confidential rulings from officials that ensure a very low effective tax rate — in many cases less than one percent.

The ICIJ’s reporting and detailed analysis of documents on individual companies from Disney to IKEA is outstanding. It clearly shows a systematic pattern of behaviour in Luxembourg, and adds to a range of other evidence suggesting the pattern is systematic across multiple jurisdictions.

Widespread tax base poaching

Several recent examples show other countries doing deals knowingly to shift in, and not (fully) tax, profits that arose elsewhere. The European Commission has initiated proceedings against Ireland for allegedly providing “State Aid” to Apple since the 1990s through unjustifiably beneficial tax treatment. This had effectively capped the level of profit Ireland would recognize as tax base, leaving untouched the vast majority of profit shifted in. Meanwhile, a more formalized version of this approach dating back 10 years, Belgium’s system of ‘excess profits rulings’, has also come under scrutiny.

In all three cases—Luxembourg, Ireland, and Belgium—the pattern is consistent. Companies, through their big four accounting firm advisers, have obtained advance agreement not to tax profits that arise, but are not taxed, elsewhere.

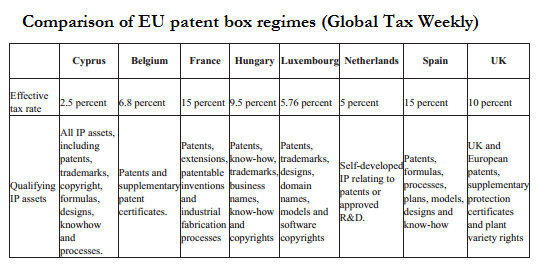

A less blatant but increasingly common instrument is the patent box, or knowledge box, which provides a very low tax rate in relation to R&D. There are already generous tax breaks for R&D in most countries. A patent box can, controversially, allow one country to capture the tax base associated with the R&D that was supported by taxpayers in another.

Such tax incentives for intellectual property exist in Belgium, Cyprus, France, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Spain. In addition, the UK, which had introduced the measure from 2013, recently bowed to German pressure to phase it out (albeit not fully until 2021). The decision came after initially resisting, along with Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Spain, the suggestion that the tax break should only apply to R&D actually carried out in the country offering the patent box.

Google tax

Less than a month after its compromise over the patent box tax break, the UK government proposed a measure designed to protect its own tax base against similar poaching. The ‘diverted profits tax’ (DPT), now subject to public consultation, seeks to ensure profit arising from sales in the UK do not escape taxation by claiming to have no permanent establishment in the UK, nor through ‘certain arrangements which lack economic substance’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given criticism of theapparent disconnect between Google’s UK profitability and tax payments, media are calling the measure the ‘Google tax’.

The expected revenue impact is small. Despite a marginally penal rate of 25 percent (compared to a standard 21 percent), the forecast is to raise around £1.3 billion over five years. The highest forecast annual take of £350 million implies a base of £1.4 billion of ‘diverted’ profits, which is equivalent to just 1.4 percent of the most recent quarterly UK corporate profits. (The basis for these estimates hasnot been published.)

The change of direction may nonetheless be important. During his announcement of the DPT, UK Chancellor George Osborne stressed “the government’s commitment to an internationally competitive tax system.” However, the DPT reflects an understanding that, too often, countries are competing not to attract real economic activity but only the taxable profit that arises from activity taking place in another jurisdiction.

The tension between playing this game, while trying to limit the counter-success of others, in large part explains the failure to develop more effective international rules – and hence the tilting of benefits towards multinationals rather than to (especially lower-income) states. Still, pressure is growing, and the eventual direction of travel will have important implications for developing countries. A companion post explores future scenarios for international tax rules, and the implications for developing countries.

One Reply to “#Luxleaks: The Reality of Tax ‘Competition’”

Comments are closed.