This post was first published on Views from the Center.

Consensus on the reform of international tax rules may be splintering under the combined pressures of post-crisis austerity and revelations about cut-throat tax ‘competition’ (see my discussion on thishere). In light of this, I sketch out four possible directions for international rules and one major trend common to all, and then assess the likely implications for developing countries.

1. Staying the BEPS course

The Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative (BEPS), led by the OECD at the behest of the G-8 and G-20 countries, aims to create better alignment between multinational profits and the location of their actual economic activity. The OECD’s remit, set out in a detailed action plan, is to deliver progress in a set of largely discrete areas to make the current system function better.

The BEPS approach rests on a commitment to “arm’s length pricing” (ALP) for transactions among members of the same multinational group, which is intended to give rise in turn to the real (market-equivalent) distribution of profit across the group. Setting aside whether this is an economically sensible way of looking at a group of related parties with common control, the approach simply may not be consistent with the aim – there is no evidence to suggest that ALP, if effective, would necessarily align profit with economic activity.

The UK’s proposed ‘diverted profits tax’ embodies the challenge for BEPS. Despite playing an important role in bringing BEPS into being, the UK government’s frustration with the inability of ALP to deliver politically acceptable taxation of major multinationals has led it to take a quite different tack: in effect, to require explicitly some degree of alignment of profits and activity (sales).

Will leading states maintain their commitment to the OECD approach? The answer may depend on a return to stronger economic performance, and the easing of broader fiscal pressure. Continuing anaemic growth may lead to continuing political pressure and proliferation of work-around measures like the Google tax that cut across the ALP by requiring some alignment of profits and activity.

2. A bigger fix for BEPS

A more consensual future for BEPS can also be envisaged (hat tip to a necessarily anonymous official at a major ministry of finance), involving a rather broader fix but maintaining the fundamental nature of the current system.

This would involve countries signing up to three basic principles, which it has been suggested could eliminate 90 percent of the BEPS problem in one stroke:

- A common tax base (so there is no incentive for arbitrage on the base)

- Minimum tax rates (limiting, though not eliminating, the incentive for arbitrage on rates)

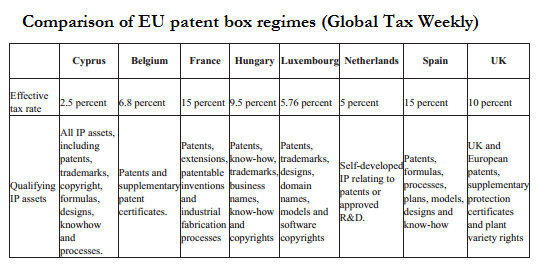

- Elimination of preferential regimes (such as the patent box)

This would require a substantial shift in perceptions of the problem. Since some policymakers see this type of harmonization as a threat to sovereignty, progress seems likely only if such a view is eclipsed by the perception of tax ‘competition’ as the greater threat.

3. Unitary tax revolution

The most dramatic change conceivable would involve broad agreement to adopt the major alternative to the ALP, which is unitary taxation with formulary apportionment. In other words, the new approach would take the multinational group as the unit for taxation purposes, rather than individual companies within it, and apply a formula based on the location of economic activity to apportion the group’s tax base between different jurisdictions, where each may apply whatever level of tax they choose.

Given this approach is explicitly designed to align profits with economic activity, progress towards the agreed aim of the BEPS initiative is highly likely, and would benefit lower-income countries. While pressure for lower rates might build over time, the increase in tax sovereignty – the ability to make policy changes that matter – would remain.

However, political opposition has hindered the prospect of a global agreement to rip up the rules and start afresh. EU attempts to move towards an apportionment basis under the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base project appear stalled, and major powers like the US (despite its largely positive experience using unitary taxation among its own states), and the vast bulk of the multinational and accounting sectors continue to oppose, rendering a revolution unlikely in the medium term at least.

4. Unitary tax evolution

A more likely scenario is one where the current system evolves gradually towards something more consistent with unitary taxation (UT). There are two main, complementary channels through which this could occur.

First, continuing dissatisfaction with the ALP – and the sense that developing countries’ concerns are not well reflected in BEPS – may give rise to a breakaway. Developing countries will soon be able to examine country-by-country reporting from multinationals operating in their jurisdiction, which will highlight the misalignment between the shares of activity hosted and shares of profits declared.

A single developing country or a regional grouping could reach a tipping point and decide to switch unilaterally to taking as tax base some formulary apportionment of the global profit. The demonstration effect could be powerful and drive others to follow suit.

The second channel is even more gradual. It involves the ongoing growth in the diversity of methods allowed under OECD rules and the use of methods that include some profit attribution on the basis of activity, as distinct from any ALP or other pricing decision.

Between the two channels, the world seems likely – ceteris paribus – to move at least a little further in this direction over time. Again, this scenario would offer the possibility of greater tax sovereignty for many developing countries.

Development prospects and a common trend

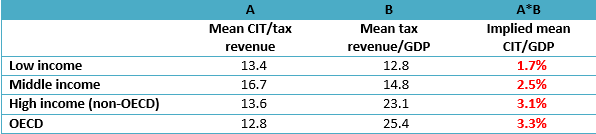

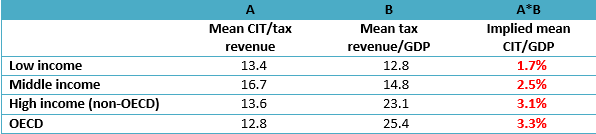

Lower-income countries obtain, on average, much smaller shares of GDP in corporate tax revenue. In no small part this is due to a combination of limits to states’ technical capacity and negotiating power with large multinationals, and to the incentives that the international system provides for profit-shifting. As such, the four futures can be considered in terms of their likely impact on these two factors.

Source (columns A and B): McNabb & LeMay-Boucher, 2014; data from ICTD Government Revenue Dataset.

The BEPS course (future 1) address specific weaknesses in the rules, which may reduce profit-shifting incentives somewhat, but at a broader level will do little to diminish the complexity of rules that make technical capacity such a constraint. The ‘bigger fix’ (2) offers the possibility of greatly reduced incentives for multinationals, and so could have an appreciable benefit.

The unitary revolution (3) could change the power dynamic for lower-income countries entirely, both in relation to multinationals but also vis-à-vis higher-income countries – but partly for this reason is an implausible scenario. Evolutionary steps towards UT (4), however, seem likely, and have the potential to sharply reduce the importance of capacity constraints and to change the balance of negotiating power also.

In fact, the common trend in all four futures is in this direction. The presence of country-by-country reporting information, now established as OECD standard, provides a simple risk mechanism by allowing a check on the profit misalignment of each taxpayer. Any tax authority requiring this information from multinationals will be in a position, regardless of the range of possible outcomes under ALP (or directly under UT), to set effective limits on the extent of profit misalignment that they are willing to accept. This has the potential to change the relative negotiating power of even the least well-resourced tax authorities.

Publishing the data would provide a powerful accountability mechanism for both multinationals and tax authorities, in respect of each other and for civil society; but even held privately, this is information that can support substantial change. Not all transparency is equal; in this particular case, information is indeed power.