A draft paper by Maya Forstater, circulated by the Center for Global Development in time for the Financing for Development conference in Addis, attacks the integrity of many people and NGOs working on tax justice and illicit financial flows.

The claims include:

- that (some?) NGOs have “contributed to unrealistic public expectations and an appetite for an overly simplistic narrative about a corporate tax ‘pot of gold’” (p.31);

- that (some?) NGOs tolerate “exaggerated interpretations and misunderstandings”(p.33);

- that (some?) NGOs do not “engage honestly with debates over economic trade offs [sic]” (p.33); and

- that this behaviour is comparable to “the use of exploitative and prejudiced imagery in charity appeals” (p.34).

Blimey.

This is a (really) long post, as I’ll try to cover the breadth and strength of Maya’s many claims. I should say that I took part in the first of two meetings of the group CGD convened to look at the issues. This was really quite a constructive coming together of different viewpoints. But I stood down when the subsequent blog post seemed to ignore most of the common ground and reiterated some earlier attacks on NGOs instead, making some claims about ‘inconvenient truths’ that resurface here. Comparing back, I’m afraid it seems as if the results of the research exercise were pre-determined.

Some main points from the discussion below:

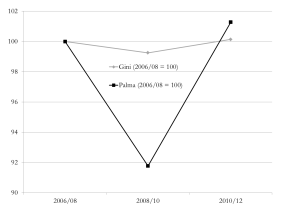

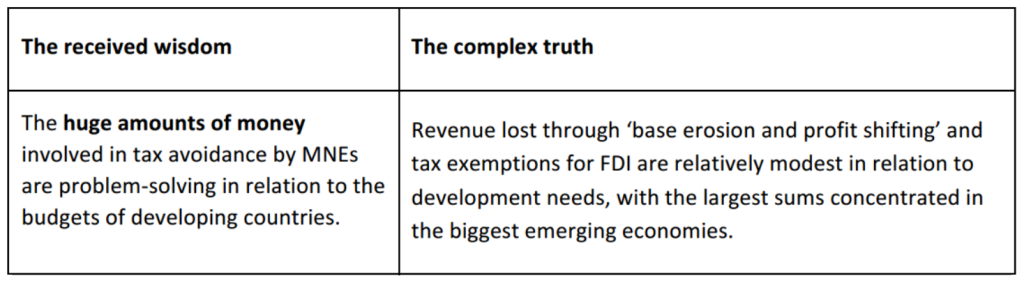

- The draft paper makes a series of claims without providing any serious evidence: most importantly, a ‘complex truth’ that tax losses are not of ‘problem-solving’ scale but ‘relatively modest in relation to development needs’. The existing evidence, e.g. from the IMF or – strikingly! – the author’s own analysis in this paper of ActionAid’s work, clearly supports the opposing view.

- In the two other cases where ‘received wisdom’ associated with NGOs is contrasted with ‘the complex truth’, there is in fact no direct contradiction – but the presentation in each case creates an implicit straw man of NGO opposition to the truth.

- The paper’s main thrust is that there is no ‘pot of gold’ for developing countries – but no substantial evidence is offered to support this assertion. (I’m sympathetic to the idea that this aspect of the tax justice agenda is sometimes overstated, but simply to deny the existing evidence offers no way forward. Indeed this is why I encouraged this work to focus instead on substantive research issues, albeit to no avail.)

I should point out that I was a research fellow at CGD during 2013-2014, and remain grateful to Owen Barder and colleagues for giving me a great deal of space to pursue research in just this area. I hope it may be possible to revise the final draft in such a way that it can make a useful contribution.

Measuring the illicit

The bulk of the attack in the draft paper is dedicated to three elements of ‘received wisdom’, each of which are contrasted with a quite different ‘complex truth’, so I’ll focus on these before coming back to the overarching claims. First, a little bit of context.

As has often been remarked, attempts to estimate illicit financial flows (IFF) are inevitably fraught with difficulty.

By definition, illicit flows are those ‘forbidden by law, rule or custom’: so whether or not they are technically legal, like large-scale tax avoidance, they are always hidden from view where possible. Add to this the fact that the relevant international datasets are often of less than ideal quality and coverage, or sometimes simply held in private by multilateral organisations who should know better, and the problem is of estimating things that are deliberately hidden, on the basis of anomalies in data that are imperfect in any case.

The development of the research field – which has come into being seriously only in the last 15 years – has been led by NGOs, perhaps because academic researchers felt uncomfortable with the degree of uncertainty, or because those at international organisations didn’t see it as a policy priority. At each stage, NGOs and the few academic researchers have challenged international organisations to use their capacity, and ability to access data, to do better; but until this year, there had been no serious response on any aspect of IFF except that of UNODC and the World Bank in their Stolen Assets Recover (StAR) initiative.

Following the G20 meetings in 2009, however, the issues originally promoted by NGOs in the wilderness rocketed to the top of the global agenda. Then in 2013, the G8 and G20 commissioned the OECD to carry out the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative (BEPS), aimed at reducing the misalignment between the location of multinational companies’ economic activity, and where they declare taxable profits.

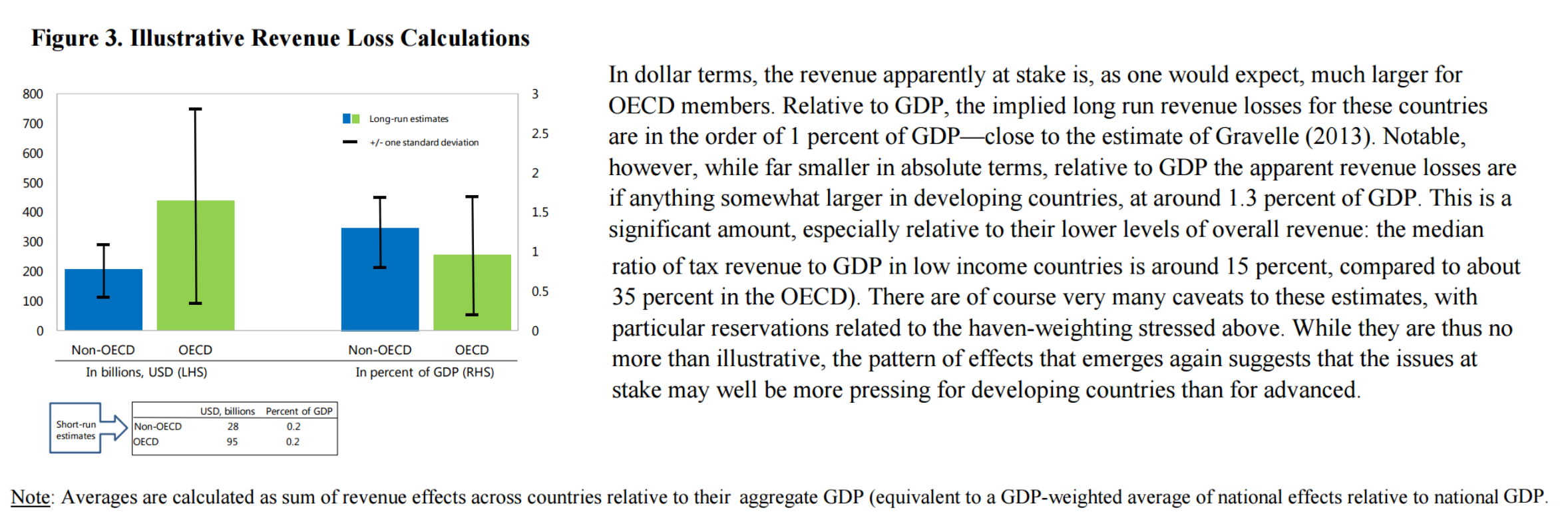

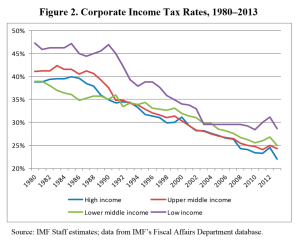

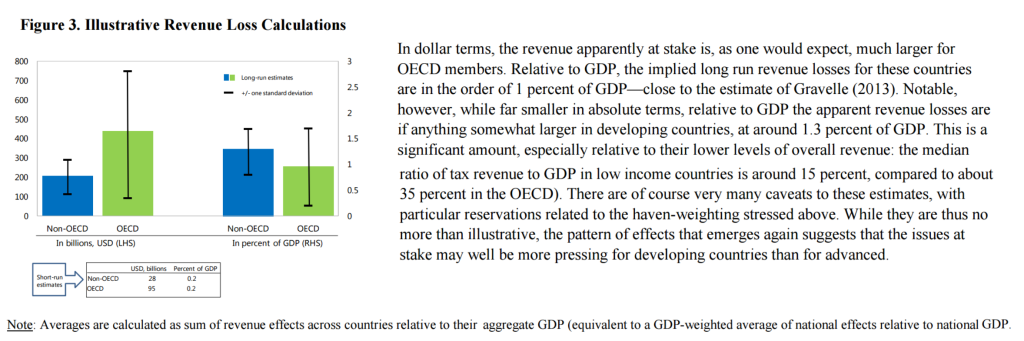

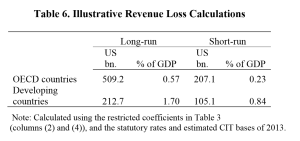

This year, the resulting research focus of international organisations has borne interesting fruit. The UNCTAD World Investment Report contributes a study estimating developing country revenue losses to one channel of multinational tax abuse at $100 billion per year. Furthermore, researchers at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department suggest, in their Table 6, that the total developing country losses due to BEPS stands at $212 billion per year (in the long-run), or around three times the share of GDP of the losses of OECD members (around $500 billion). It’s worth highlighting that the developing country losses would on average exceed 10% of existing tax revenues.

None of this is to say that we don’t have a long way to go, not least in terms of collating additional datasets, and making existing ones fully available, and in burying down to the country and then the company level; and in methodological improvements, as in any quantitative research field. (Bring it on!) And just because they come from international organisations, these studies themselves are of course not immune from criticism.

But while many aspects of IFF remain ill-estimated at best, and the leading estimates from GFI for example do not include many of the aspects related to multinational tax behaviour, there is no question that thanks to the recent UNCTAD and IMF reports we are in a better position than ever before in terms of understanding the scale of revenue loss associated with multinational tax behaviour in developing countries.

Assessing the ‘received wisdom’

The main section of the paper outlines three ideas, labelled as ‘received wisdom’, and contrasts each with ‘the complex truth’. The three ideas are not specifically attributed to one or more NGOs; rather, “they are a set of perceptions which are often given and reinforced by the overall flow of media reports, infographics, press releases, case studies and campaign publications on this topic and are influential enough to require clarification” (p.9).

The sub-headings here are taken from the draft paper.

Idea 1: ‘Huge amounts’

Let’s consider first the attribution of this idea to NGOs, and second its truth or otherwise.

Let’s consider first the attribution of this idea to NGOs, and second its truth or otherwise.

Of the three quotes to support the claim that NGOs have promulgated the ‘received wisdom’, one is indeed a clear overstatement of the case, taken from an NGO infographic; one is a newspaper headline (which refers to an NGO report that I’m guessing doesn’t make the claim itself, or would have been used directly); and one is a statement (that strikes me as defensible) from Yale professor of philosophy Thomas Pogge.

Even with this level of cherry-picking, these quotes obviously provide less than compelling evidence if you want to make the case for NGO responsibility for the narrative. But to be fair, I’d say that many NGOs and people (like me!) do indeed think the revenue impact could be ‘problem-solving’, if that means something like ‘with the potential to provide a noticeable human development benefit’; so let’s set the paper’s evidentiary approach aside for now.

To get to the substance of the claim, we need to compare what the paper calls the ‘received wisdom’ and ‘the complex truth’. There are two important ideas being combined here. One is about scale: the difference between ‘huge’, or more usefully ‘problem-solving’ amounts of revenue, and the alternative that these are ‘relatively modest in relation to development needs’. The other is about location: the question of whether the revenues that could be available would appear in richer rather than poorer developing countries.

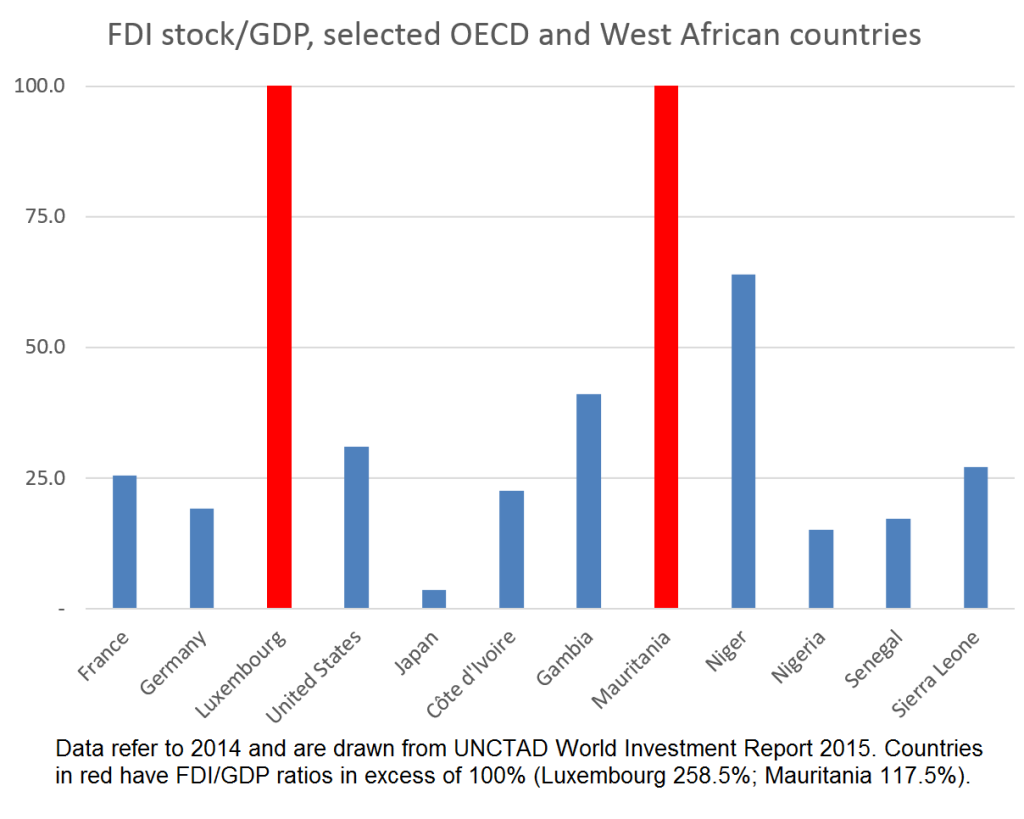

Maya has made some useful points on the latter before, complaining rightly that the aggregation into ‘developing countries’ can hide a mismatch between revenues and development need. This doesn’t take into account the role of inequalities that mean most people living in extreme income poverty do so in middle- rather than low-income countries, but the broader point holds: aggregation can obscure meaning.

From the summary: “Any potential gains are likely to be higher in middle income emerging economies, and lower in the poorest countries, in line with levels of FDI although extractive industry rents are likely to offer a significant focus for greater domestic revenues in some countries” (p.2).

It might have been better to consider the data on FDI. While it is true in general that bigger economies have more FDI, the pattern is much more mixed – even allowing for natural resource wealth. Here’s a quick figure with an arbitrary selection of OECD and West African countries, just to highlight that risks of sweeping generalisations are not limited to NGOs.

And of course if the claim is about the relationship between FDI and revenues, and we know tax/GDP is strongly correlated with per capita GDP, then lower FDI/GDP in poorer countries might still be associated with higher (relative) potential revenue contribution (i.e. the FDI stock, and hence potential revenues, might still be higher in relation to current tax revenues).

And of course if the claim is about the relationship between FDI and revenues, and we know tax/GDP is strongly correlated with per capita GDP, then lower FDI/GDP in poorer countries might still be associated with higher (relative) potential revenue contribution (i.e. the FDI stock, and hence potential revenues, might still be higher in relation to current tax revenues).

In addition, the paper doesn’t provide any evidence for the claim about the scale of development needs, which seems odd. It does not to provide (nor seek to provide) any proof that the amounts involved would not have powerful effects in low-income countries.

Well; in fact, it does in one particular case.

A box on Malawi (page 12) provides probably the clearest example of why I find this paper so disappointing – what could have been offered as a useful check on use of statistics, descends instead into the absurdity of inadvertently demonstrating the truth of the position being attacked.

The box summarises ActionAid’s work [disclosure: I’m on ActionAid UK’s board] on the mining company Paladin, finding that it cut its tax bill by $43 million, and states that in one year this could have paid for “one of the following: 431,000 HIV/AIDS treatments, 17,000 nurses, 8,500 doctors, 39,000 teachers”.

It is then pointed out, accurately I assume, that the tax revenues relate to six years; and argued that it would be more appropriate to identify what could be achieved annually with the relevant share of the money (rather than offering mutually exclusive alternatives).

The annual bundle of potential services that the foregone tax could pay for, according to the draft paper, is this:

- a doubling in the number of doctors, AND

- a 10% increase in the number of nurses, AND

- enough teachers to reduce average class sizes from 130 to 100, AND

- 2% of needed HIV treatments.

I guess we could argue about whether or not to call this ‘huge’, though it wouldn’t be a very useful argument. But I don’t see how anyone could deny it is a problem-solving level of revenue.

Would ActionAid have been better to present the statistics this way? Perhaps.

Does it detract from the substantive value of the ActionAid report in any way? No.

Does it support the ‘complex truth’ claim that the amounts involved are modest in relation to need? Quite the reverse – it is stark evidence to the contrary.

The draft paper has taken a potentially useful contribution, dressed it up as an attack, and lost most of its value.

Thinking at the global level, and of the 1.7% of GDP that the IMF sees as long-term annual revenue loss: it is perhaps possible to imagine a distribution of those revenues among countries in which the resulting allocation fails to be ‘problem-solving’ for most; but it’s hardly a claim we could provide evidence for at the moment, and this draft paper certainly does not.

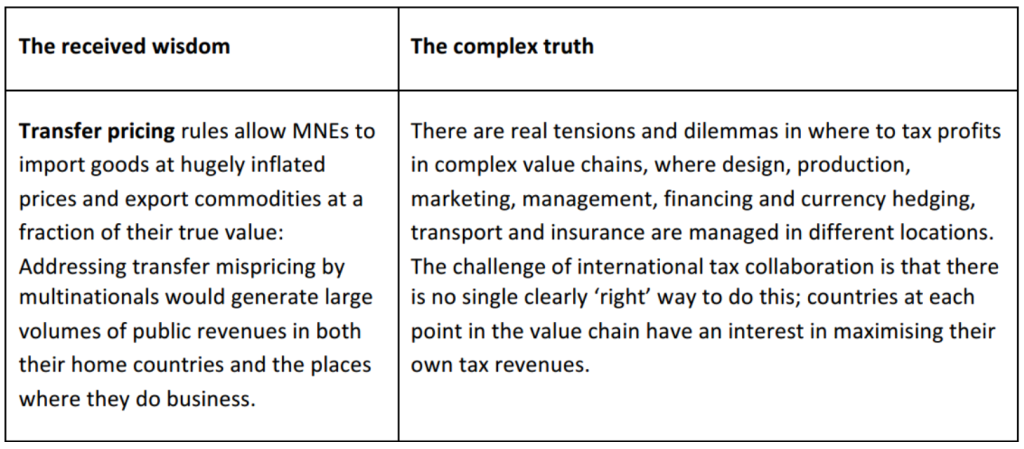

Idea 2: Transfer pricing is tax dodging

The second aspect of ‘received wisdom’ attacked in the paper is a little confused. Per the heading and some of the discussion, it is simply the confusion of transfer pricing with tax dodging. Per the box text, however, and other discussion, it is more about whether or not transfer pricing and related rules allow multinationals sufficient room to manipulate prices, via ‘tax havens’, that curtailing this could generate significant revenues elsewhere.

Again, let’s look first at the attribution. The only quotes provided that support the confusion point come from respected academics, rather than NGOs. My feeling is that there is sometimes a confusion of language here, but the fundamental points (that there are rules in place, and that these may sometimes be abused and may sometimes allow distorted outcomes) are widely accepted by the world’s most senior policymakers.

The more interesting distinction is drawn between ‘received wisdom’ that associated revenue implications are large (for countries on either side of ‘profit havens’, as seen in #LuxLeaks); or the ‘complex truth’ that allocating profits within global value chains is difficult.

I must confess I find this one quite confusing. There’s no obvious contradiction between the ‘wisdom’ and ‘truth’. You rarely hear anyone claim international tax rules are simple or easy to comply with (for either multinationals or tax authorities); and it’s almost equally uncommon to hear a suggestion that there aren’t major revenues at risk in a whole range of countries – see e.g. the details of LuxLeaks, or the IMF results shown above.

There just doesn’t seem much disagreement to be had over whether transfer pricing rules are being exploited, to the benefit of many multinationals and a few secrecy jurisdictions, and the (revenue) loss of many countries (with both higher and lower per capita incomes) – at least not in the absence of some pretty striking new evidence.

The existence of complexity doesn’t reduce the revenues at risk, nor justify taking advantage of complexity (nor indeed lobbying to create or retain complexity). And it certainly doesn’t provide evidence against the ‘received wisdom’ suggested, so I think this section really weakens the draft.

The associated paragraphs largely focus on criticisms of some existing work with commodity trade data (including Maya’s very reasonable criticism last year of a Swiss-Zambia mispricing statistic for which I’m responsible). The discussion of the various broader studies in this draft paper is fairly light touch though. It raises a few questions on individual results, and we can easily agree that there is a good case for being cautious about data and methodologies in this area. But what of all the peer-reviewed, academic analysis that is left out?

The failure to engage with the vast bulk of the literature covered in the OECD’s recent BEPS 11 survey, for example, seems odd. The exclusion of pricing issues in relation to management services, intellectual property and debt – for example – seems doubly so. Even if the commodity critique was entirely valid, this section would not provide evidence against the ‘received wisdom’ that it intends to attack. And in addition there is now a range of analyses of individual multinational groups published by forensic investigative journalists of high quality, which go well beyond anecdote.

If we think of international corporate tax rules as the broader set within which TP rules sit, the entire BEPS process is a reflection of significant political and technical consensus on this problem. Do we have enough consistent data, or sufficient quantity of research as a result, to be precise about the scale and overall pattern of the problem? We do not, and this is the subject of much attention at the OECD, Tax Justice Network and elsewhere. Are we unsure about the broad contours of the problem? We are not. Transfer prices of everything from commodities to intellectual property to intra-group debt are manipulated for tax purposes. The scale is large, and uncertain.

The author is of course entirely at liberty to take a different view, and it would be welcome to see supporting evidence for such a position. But without presenting some pretty impressive new findings, I can’t understand why one would simply dismiss the broad consensus that exists, or seek to build a difference of opinion on the scale of a problem into an argument that the entire thing is a (deliberately?) misleading ‘narrative’ created by NGOs.

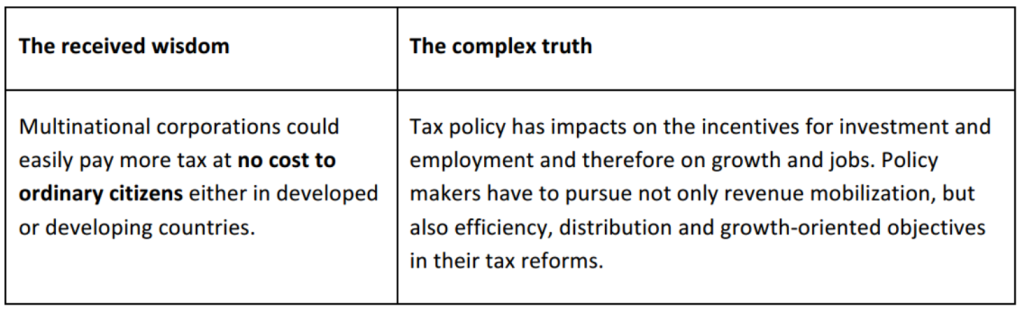

Idea 3: Money for nothing

Perhaps anticipating the reader’s scepticism by this stage, this section begins by noting: “Examples of this belief are rarely seen as direct statements” – this much is certainly true – “but often reflected in the implicit assumptions behind calculations of lost taxes…” (p.18).

The TJN quote offered as supporting evidence is intriguing:

“…tax-sensitive investment is by definition the least useful stuff: accounting nonsense and paper-shuffling that does not involve very much employment creation at all.”

Intriguing for two reasons. First, it doesn’t seem to bear directly on the ‘received wisdom’ claim. But second, because the missing start of the sentence is “But as Section 3.3 explains…” And section 3.3 includes a short literature survey with six references on the incidence and impact of corporate tax. Neither the survey nor any of the references are cited in the draft paper.

Instead, the main thrust of this brief section of the paper is to emphasise that (higher effective) corporate taxes can have negative dynamic effects. A selective survey of a few papers supporting some of these leads to the following conclusion:

“These arguments then, are not reasons to give up on taxing corporations, or necessarily to lower corporate tax rates, but underline the need for tax policy to be supported by economic analysis, rather than based on the assumption that there is ‘money for nothing’” (p.18).

If you believe in the existence of this particular ‘received wisdom’, even without any direct evidence being presented, then this is presumably a useful counter-point: we should be more careful to recognise the wider impacts of taxing corporate profits.

In any case, that’s hard to argue with – so hard, in fact, that you want to ask who would argue to the contrary? Here’s the implicit straw man that the paper has constructed:

“Tax policy should not be supported by economic analysis, but instead be based on the assumption that there is ‘money for nothing’.”

There may be a group of people who believe this (or there may not); and if there were, such a group might object to ‘the complex truth’ of policymakers actually having multiple objectives.

But if there is such a group, it presumably has little overlap with those people and NGOs like TJN that have been researching and advocating over the last fifteen years for a tax policy agenda based on economic analysis, rather than one that ignored the growing reality of abusive multinational tax practices; and for the importance of taking into account multiple objectives such as distribution.

It’s disappointing, and difficult to understand, that the paper would seek to attribute this straw man to those people and NGOs.

Summary: Straw men

It’s hard to see the contribution of this main section of the paper. The ‘complex truth’ with respect to idea 1 is a set of assertions lacking evidence, while any remaining objections to the ‘received wisdom’ are questions of scale that must be addressed by serious research. The ‘complex truth’ in relation to ideas 2 and 3 is hardly disputed, but does not contradict the main points of the ‘received wisdom’.

So the overall effect is to suggest that NGOs hold, or have promoted, extreme or unnuanced views that somehow contradict the known facts. That there is, if you like, in fact a received wisdom which the NGO narrative continually contradicts.

There are two main problems with this. First, the paper does not provide any serious evidence either for its own assertions (on which the entire argument hangs), or that any wrong views (disagreeing with an actually true ‘complex truth’) are in fact held or promoted by NGOs.

And second, even if a new draft were to do so – I’m just not sure that this is a useful way to make an argument: defining the righteous view, and implying that others disagree (or perhaps that they dishonestly pretend to).

That pot of gold

Ultimately, the CGD paper makes the argument that NGOs have exaggerated the ‘pot of gold’ that developing countries could obtain by better taxation of multinationals.

To be upfront on this, I share something of this concern. Specifically, I think the balance of attention here, compared to other aspects of tax systems, has not always been right. (At the same time, I can see good arguments for emphasising this aspect in certain policy situations.)

What do we actually know about the size of that pot though? Notwithstanding all the uncertainties discussed, and the importance of new data and continuing to improve methodologies, the best guess at the moment is probably somewhere near the latest IMF researchers’ piece: that developing country annual revenue losses might be around $200 billion, or north of 1.5% of GDP. Given average total tax revenues less than ten times that size, it’s a pretty big pot. (And all without mentioning the trend for rising shares of profits to GDP, and generally stable or falling corporate income tax revenues…)

That doesn’t mean the pot is all obtainable, or that important advances in other areas aren’t also possible, and clearly we need country-level analyses to understand the specific possibilities. But on the CGD paper’s terms, and in respect of its central claim, this is a decent pot of gold. And not one that rests on the work (or the word) of NGOs, if that’s a concern.

So if we put the mischaracterisation of the narrative, and the role of NGOs aside, the central claim of the paper just does not stand up well itself.

My final sadness about the paper is this. The last section proposes some recommendations for NGOs to improve their ways of working that are really worth discussing.

It may be difficult to move towards positive engagement based on their inclusion in a paper that makes this kind of sustained integrity attack, but I hope it may somehow prove possible to take the conversation forward in a different context.

Last thought: Does it matter?

Despite the claim to be serving the cause of better evidence and clearer debate, the draft paper muddies the waters on the potential revenue benefit from improved taxing of multinationals in developing countries – even as the evidence base has recently been further strengthened.

The timing of its being published, at the kick-off of the Financing for Development conference – the best UN opportunity in years (ever?) to lock in greater policy space for the taxing of multinationals by developing countries – is unfortunate.

The Center for Global Development is an important development think tank, and so this paper, even in draft, may well catch the attention of policymakers at Addis. And while CGD publish individual views rather than institutional ones, this may be seen as more than an individual view because it comes from a CGD process with an advisory group.

For the avoidance of doubt, I don’t think there’s any agenda at CGD – so I guess the content of this paper, its timing and any potential impact on FFD progress is just bad luck.

I very much hope that the final draft of the paper, if indeed there is one, will be quite different. A removal of the most polarising claims, where these are made on the basis of limited or no evidence, would be a good start. What would be valuable instead is a concerted examination of the data and methodologies that have been used for various aspects of revenue loss and other IFF estimates, in order to point the way forward to a strengthening evidence base over time. I hope this is a possibility; but I fear the paper may end up as a missed opportunity to contribute to an important policy research debate.

But: be not downhearted: there is substantial policy focus around the world on taxing multinationals, the research field is healthy and the agenda for new work is plentiful!

And, you know…

Hello Addis! That’s right #globaltaxbody is in…#FFD3 pic.twitter.com/V5ZSYBZ1NK

— Global Tax Body (@GlobalTaxBody) July 13, 2015

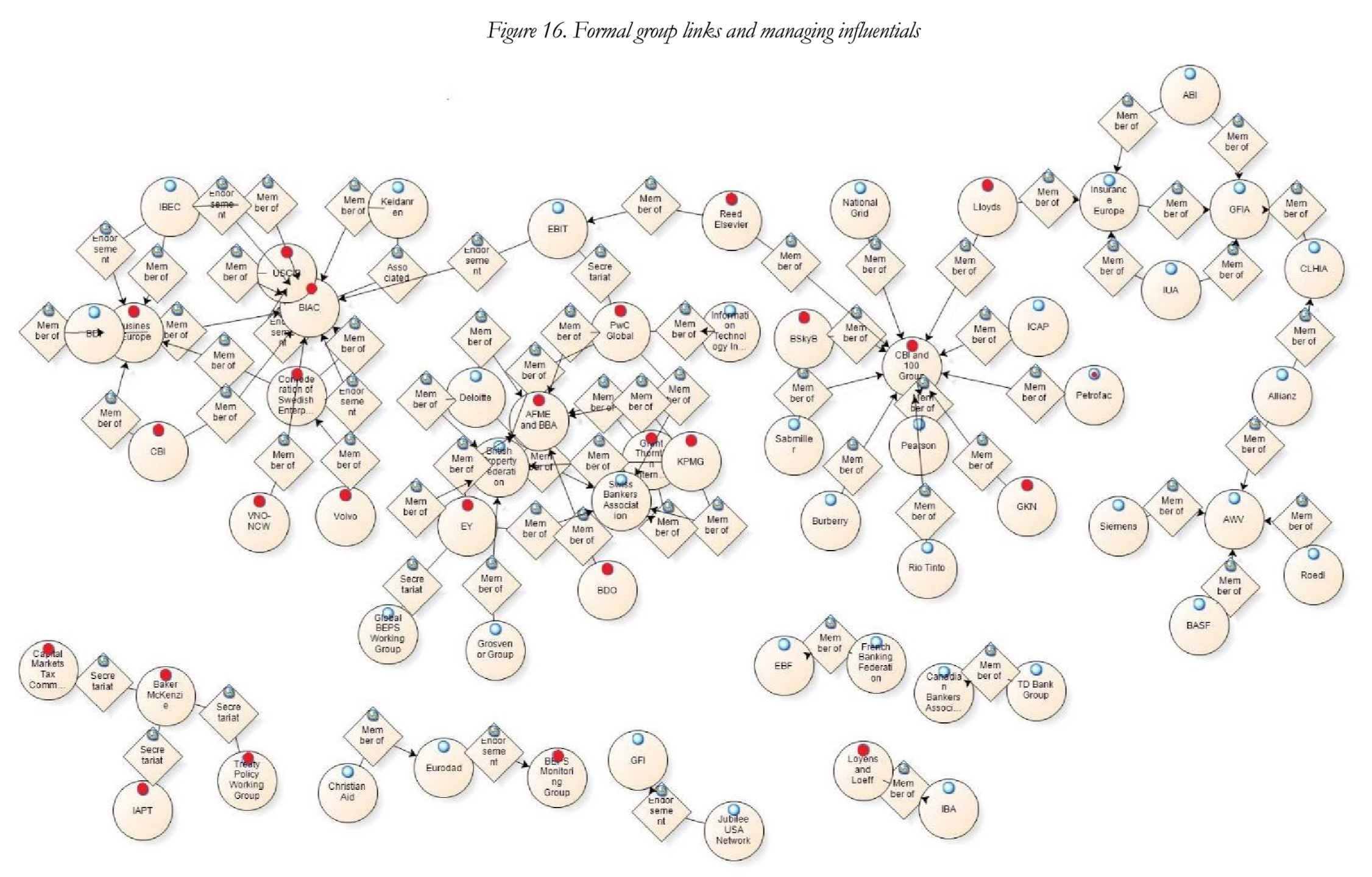

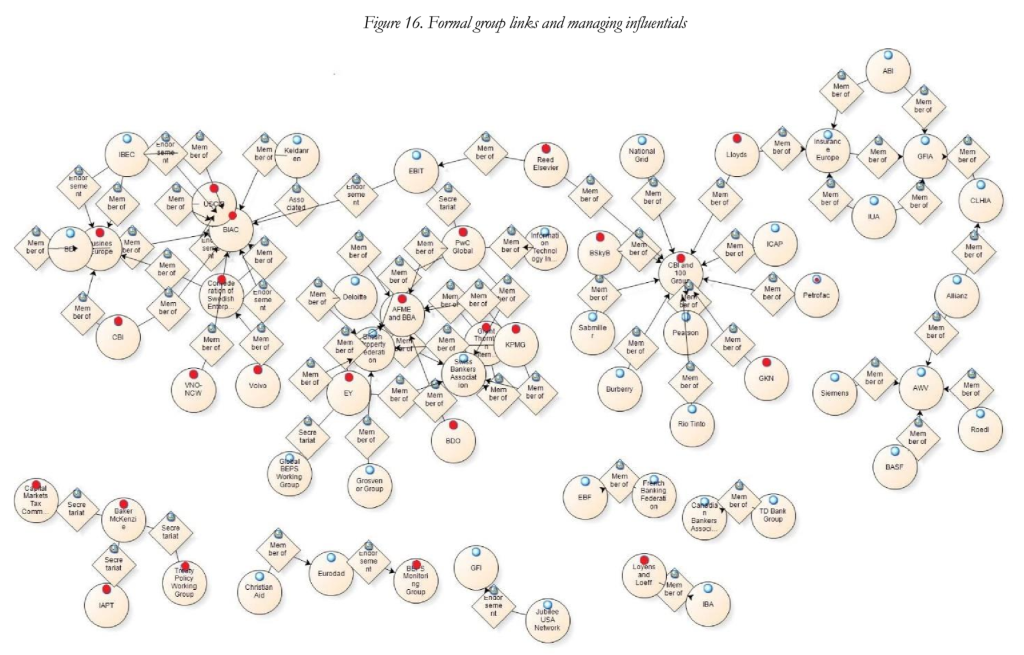

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process. The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions: