There have been substantial advances over recent years in both policy and research on taxing multinationals, especially in developing countries, so with the Financing for Development conference gearing up in Addis, it’s a good time to step back and think what current priorities for the research agenda might include.

Arguably, we understand more now than we have ever done about the revenue losses of developing countries in particular; but there’s much more to be done in relation to not only the scale but also the distribution and impact of those losses, and more besides. Here are a few ideas in three areas that stand out: scale; practical success; and national-level data.

Scale and impact

There have been important new contributions to the literature which estimates revenue lost due to profit being recorded elsewhere than the location of the economic activity giving rise to it. But there remains a great deal more to do, both to identify the scale and pattern of revenue losses, and to prioritise policy responses for individual African countries and at regional and continental level.

The aim of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative – the major international effort led by the OECD over 2013-2015, at the behest of the G8 and G20 groups of countries – is to reduce the ‘misalignment’ between profits and real activity, in order to ensure tax is paid in the right place.

A significant problem for the BEPS process relates to Action Point 11, which requires the collation of data in order to establish a baseline for the extent of profit ‘misalignment’, and the tracking of progress over time. As the most recent BEPS 11 output highlights, currently available data – whether from corporate balance sheet databases (see e.g. Cobham & Loretz, 2014), or from FDI data – is not sufficient for the purpose.

Within the limitations of existing data, however, this year has seen two important new studies of the extent of profit ‘misalignment’. First, UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2015 includes a study on the effect on reported taxable profits in developing countries of investments being channelled through ‘tax haven’ or ‘SPE’ jurisdictions. They put the total revenue loss at around $100 billion a year (see also the critique which suggests this may be substantially understated). Second, researchers in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department have looked at the broader issue of BEPS and find a long-run annual revenue loss for developing countries of $212 billion.

POSSIBLE RESEARCH PROPOSALS: SCALE AND IMPACT

- Extending current work. In neither case have the estimated revenue losses for individual countries been published. As such, a valuable piece of policy research would be to take the two studies, replicate the results and strengthen them where possible, and then to assess the country-level findings in order to support the potential prioritisation of counter-efforts. Further extension could involve strengthening the current, tentative results on the linkages between tax revenues (of different types), and important development outcome (e.g. health).

- FDI surveys. An additional approach using existing data would be to use the national-level survey data compiled by a number of countries (including the USA, Germany and Japan). One such study with US data is currently underway at the Tax Justice Network.

Practical success

A second area in which there is substantial scope for research with clear policy value is in the analysis of practical success in taxing multinational companies. Research on the scale of the problem, as discussed in the previous section, has the potential to identify the relative intensity of revenue losses and therefore the countries which should prioritise some form of response – but may not point more precisely at solutions than, for example, to blacklist certain jurisdictions as inward investment conduits.

Three types of study offer the potential for more specific policy recommendations.

POSSIBLE RESEARCH PROPOSALS: PRACTICAL SUCCESS

- Identification study. A useful first step would be to take the ICTD Government Revenue Dataset (the ICTD GRD, the best available international source), and to identify those country-periods in which significant progress has occurred in raising corporate income tax revenues; along with any major common features.

- Survey. The second step would then be to conduct a survey of revenue authorities, exploring the differences in tax policy, political support and administrative approaches, to identify systematic differences – or their absence – between those cases where significant progress was seen, and not.

- Event study. A further step would be to identify major policy changes – most obviously the introduction of a large taxpayer unit at the national revenue authority, or the provision of technical capacity-building measures from bilateral or multilateral donors, and any other features to emerge from the first two steps – and to explore whether there were systematic benefits in revenue-raising across the broad panel of GRD data.

National-level data

The third area in which research proposals could be taken forward can be grouped loosely according to the involvement of national-level data. Two specific proposals can be identified. In each case, such research might be best led by, or conducted in collaboration with, a regional tax body such as ATAF.

POSSIBLE RESEARCH PROPOSALS: NATIONAL-LEVEL DATA

- Transaction-level trade analysis. Leading estimates of illicit financial flows (e.g. those of Ndikumana & Boyce, GFI and ECA) include a major component related to trade mispricing. However, these rely on national-level, or commodity-level trade data. Among other potential methodological issues, the bulk of estimated IFF are likely to relate not to multinational companies but others; although the exact proportions cannot be identified.

The gold standard is to use transaction-level data (e.g. the pioneering work of Simon Pak), and as a recent study for the Banque de France reveals, with identifying data on whether transactions are between related parties (i.e. they occur within a multinational group) or not, it is possible to identify the scale of mispricing attributable to multinationals (in the French case, causing an estimated $8 billion of revenue tax base loss each year).

Accessing such data from customs authorities would allow the equivalent assessment to be made for a range of countries, also allowing comparison across countries and potentially the combination of data to identify fraudulent mis-invoicing at each end of the same transactions. The Tax Justice Network, with Professor Pak, is currently in the initial process of such an analysis with one African revenue authority.

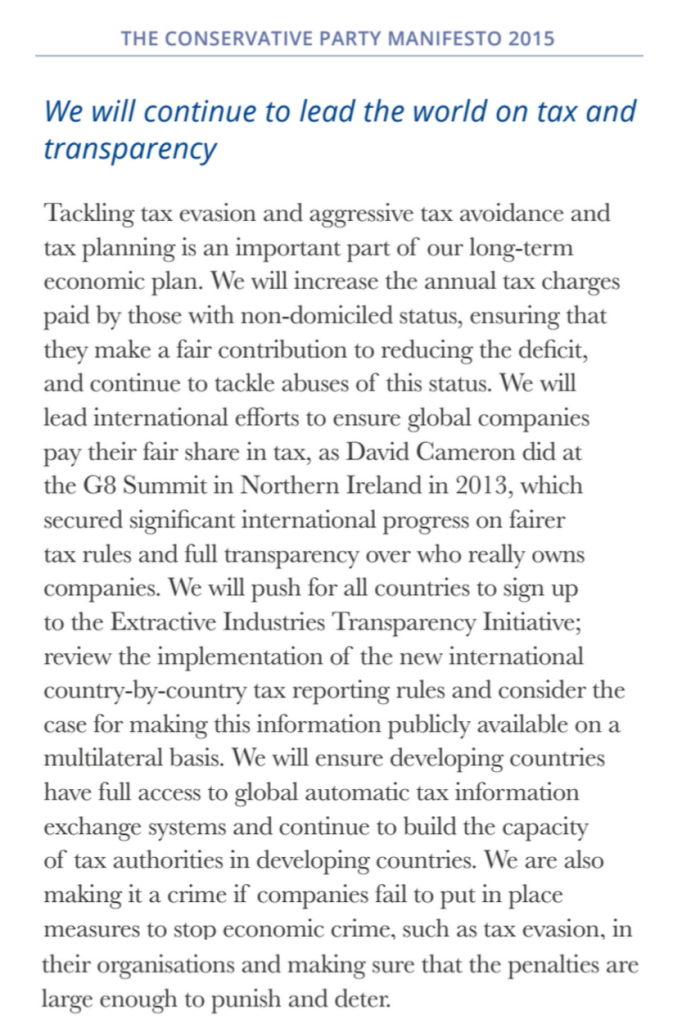

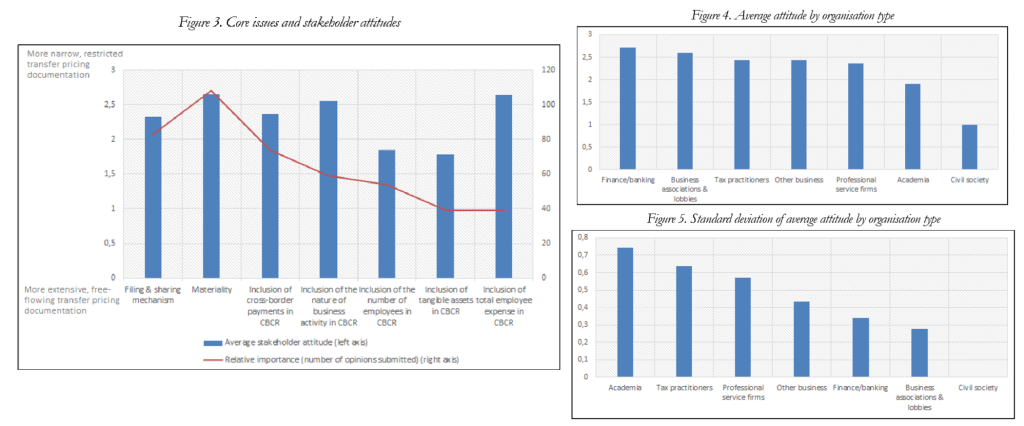

- Country-by-country reporting (CBCR). Since the fanfare of the G8 and G20 groups of countries calling for the OECD to develop a standard for CBCR by multinationals in 2013, the optimism about its value has faded. Sustained lobbying has removed not only the explicit intention of the original Tax Justice Network that the data be made public, but even that it be provided to host country tax authorities. Instead, it will be provided – if requested – to home country tax authorities, which may then provide it under information exchange agreements to host country authorities. However, the latest draft of the Financing for Development outcome document (7 July 2015) is explicit about the provision of this information directly to tax authorities in the locations where multinationals operate.

A requirement for publication is one possibility; another is for tax authorities to share the data privately amongst themselves, for example through an equivalent mechanism to the IATI registry of aid (a proposal developed in Cobham, 2014) in order to allow broader analysis and identification of revenue risks. This could happen at a regional level; but the latest noises from the OECD suggest that there will be no international collation, and hence it will be impossible to meet BEPS Action Point 11 and either to construct a broadly accurate baseline or to demonstrate the extent of progress.

Working with tax authorities, however, researchers could deliver basic results equivalent to those from CBCR. This would involve combining data reported to tax authorities through national accounts for members of a multinational group, with the global consolidated accounts of that group, in order to compare the relative shares of activity and taxable profit and hence to identify potential high revenue-risk operations.

- Investment data and vulnerabilities. There is substantial scope to improve both the reporting and use of bilateral investment stock and flow data, in order to pursue a range of types of studies. One particular opportunity, pioneered in the Mbeki report, is for the creation of measures of vulnerability to ‘tax haven’ secrecy in countries’ bilateral economic and financial relationships. Per the findings in the Mbeki report, present data are sufficient to allow significant analysis to be done, and it would be valuable to extend this to explore whether particular costs or benefits – in particular, in terms of tax revenues from multinational companies – are associated with the recorded vulnerabilities. (NB. This also points to a possible extension of the UNCTAD and IMF results in proposal 1 above.)

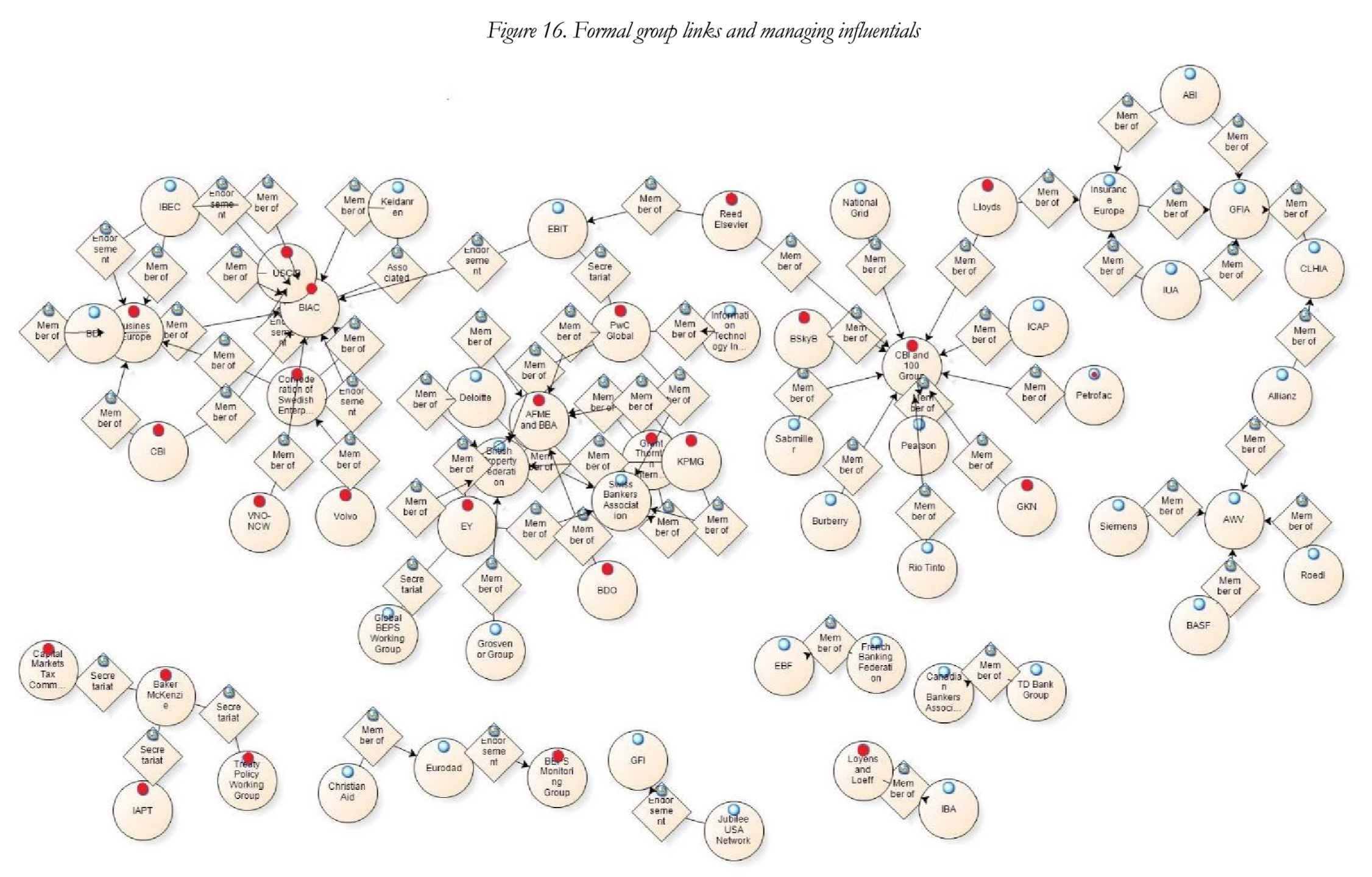

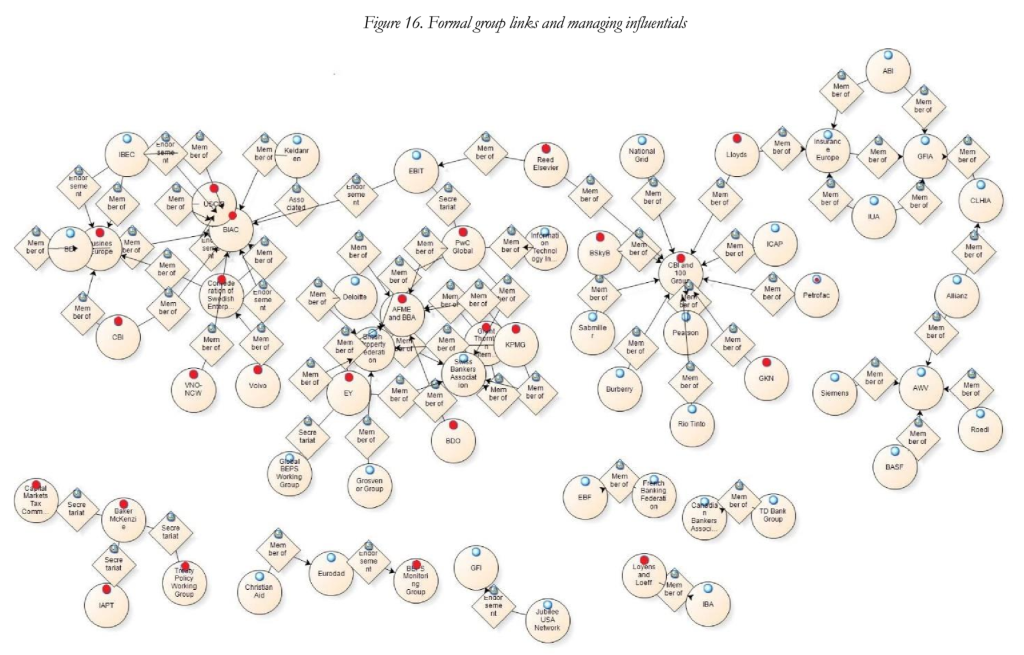

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process. The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions: