From the Tax Justice Research Bulletin 1(6).

One of many happy things about the Tax Justice Network is the range of experts involved, by discipline and by professional background. And one of the great things this gives rise to is analysis that is often so far ahead of the immediate public policy discussion that you might not even be able to see it from over there. For example…

Two TJN stalwarts from the accounting side – one an academic, Prof. Prem Sikka, and the other practitioner-turned-campaigner, Richard Murphy – have come together to address the prickly question of whether accounting data can actually be part of the solution to the corporate tax base erosion and profit shifting of multinationals.

Their working paper is published by the International Centre for Tax and Development, in its important series addressing unitary taxation. [Full disclosure, just in case it’s not completely clear already that I’m biased: I have an unrelated paper in that project, and am working with the ICTD on other stuff too.]

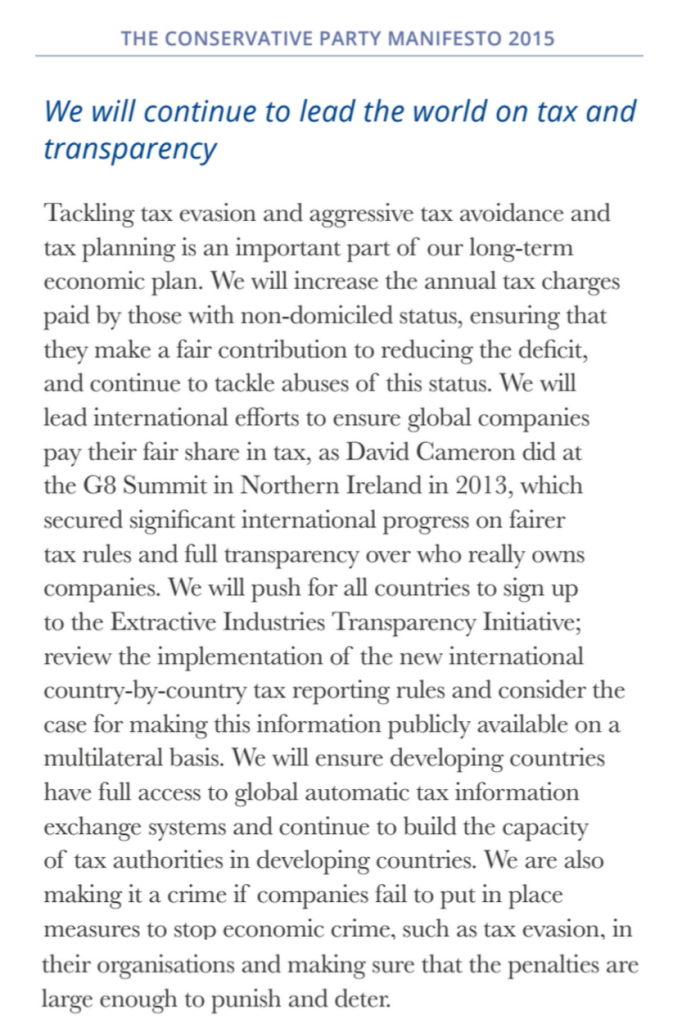

A little background: TJN started up in 2003 with a project to promote country-by-country reporting by multinationals (notably, Richard’s draft standard), as a major transparency tool to limit tax abuse. Since then this esoteric proposal has moved steadily from the extremist fringes to centre stage, with the 2013 meetings of the G8 and G20 directing the OECD to produce such a standard for global use.

One effect of this is that accounting data has probably become more central to high-level political proposals (and scrutiny) than – well, perhaps ever. (I still remember a meeting of the International Accounting Standards Board in the mid-late 2000s, marked by the then-revolutionary presence of NGOs which pointed the way forward to that greater public interest, especially with the ASC 606 changes. Happy days…)

The tendency, conscious or otherwise, has been to assume that accounting data is accurate (though not necessarily addressing the right things), and at least broadly consistent across jurisdictions. As such, it can provide the basis for powerful measure such as country-by-country reporting (for both red-flagging by tax authorities, and holding to account by civil society).

But if there’s one, top line message from the new Sikka & Murphy (2015), it’s this: accounting data does not at present provide a good basis for this greater understanding of tax. Rather, accounting data not only provides a means by which tax positions can be obscured from view; it also provides an additional vector by which tax positions can be manipulated. If your business is looking for an accounting firm in NYC to look after their money and stay legal, there are plenty of options available to you.

But if there’s one, top line message from the new Sikka & Murphy (2015), it’s this: accounting data does not at present provide a good basis for this greater understanding of tax. Rather, accounting data not only provides a means by which tax positions can be obscured from view; it also provides an additional vector by which tax positions can be manipulated. If your business is looking for an accounting firm in NYC to look after their money and stay legal, there are plenty of options available to you.

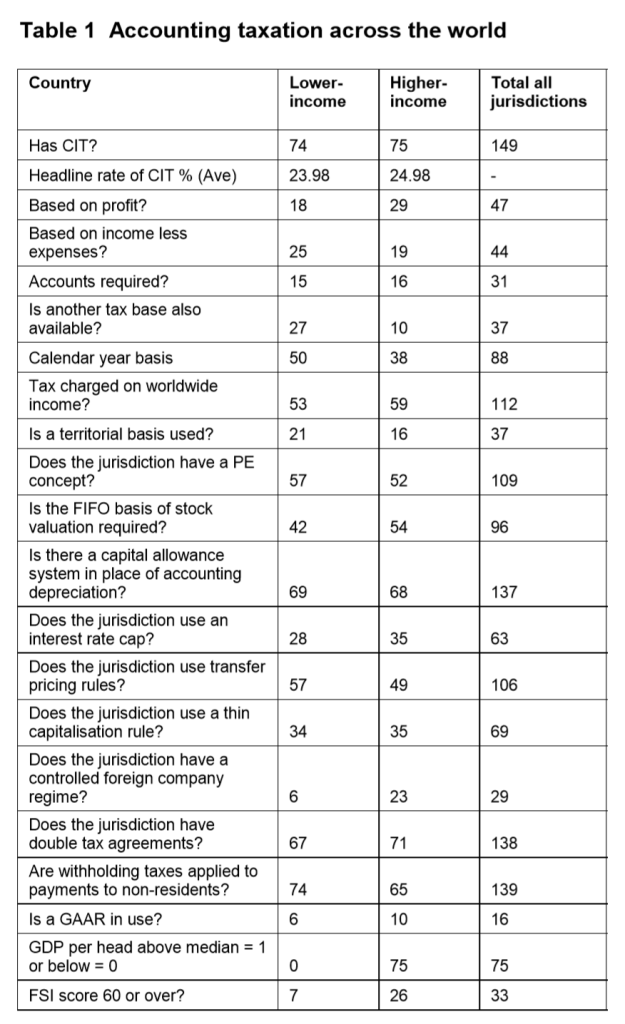

How so? The abridged Table 1 gives a sense of it (scroll down or click for larger version). The differences around the world in accounting treatment for tax purposes are manifold and fundamental. The opportunities are legion for multinationals to exploit differences in national treatment, in order to achieve preferred global tax outcomes.

Now since “no jurisdiction which we can identify relies upon unadjusted traditional accounting profit as a basis for the taxation of corporate income”, and reliance on International Financial Reporting Standards would exacerbate not ameliorate the problem, the authors argue that “tax-specific measures of income and expenses for taxation purposes need to be defined” – not least, for any proposal for a full shift towards unitary taxation of MNEs. Whether this is carried out by an accountancy firm like Faris CPA for a company or by an in house team, having this defined clearly will help all involved. Their specific suggestion is this:

“[W]e think it possible that a taxation base for unitary taxation that is broadly, but not precisely, equivalent to the accounting concept of EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation) could be developed. This resulting tax base before offset of locally-determined allowances could then be apportioned in accordance with a formula that is likely to exclude assets, because relief for expenditure on capital will be given locally and capital costs do not therefore need to be considered for formula purposes.”

Even more than usual, this summary is nowhere close to doing justice to the deep and rich set of questions that the paper raises. It’s a difficult paper, technically challenging in more than one way and requiring the reader to think well ahead. This is why people often use accounting student services to gain a better understanding of how to approach these questions. And it’s an important paper. We may not hear much about it for a while, but it wouldn’t be at all surprising to see it being referred back to as a foundational piece of problematisation in years to come.

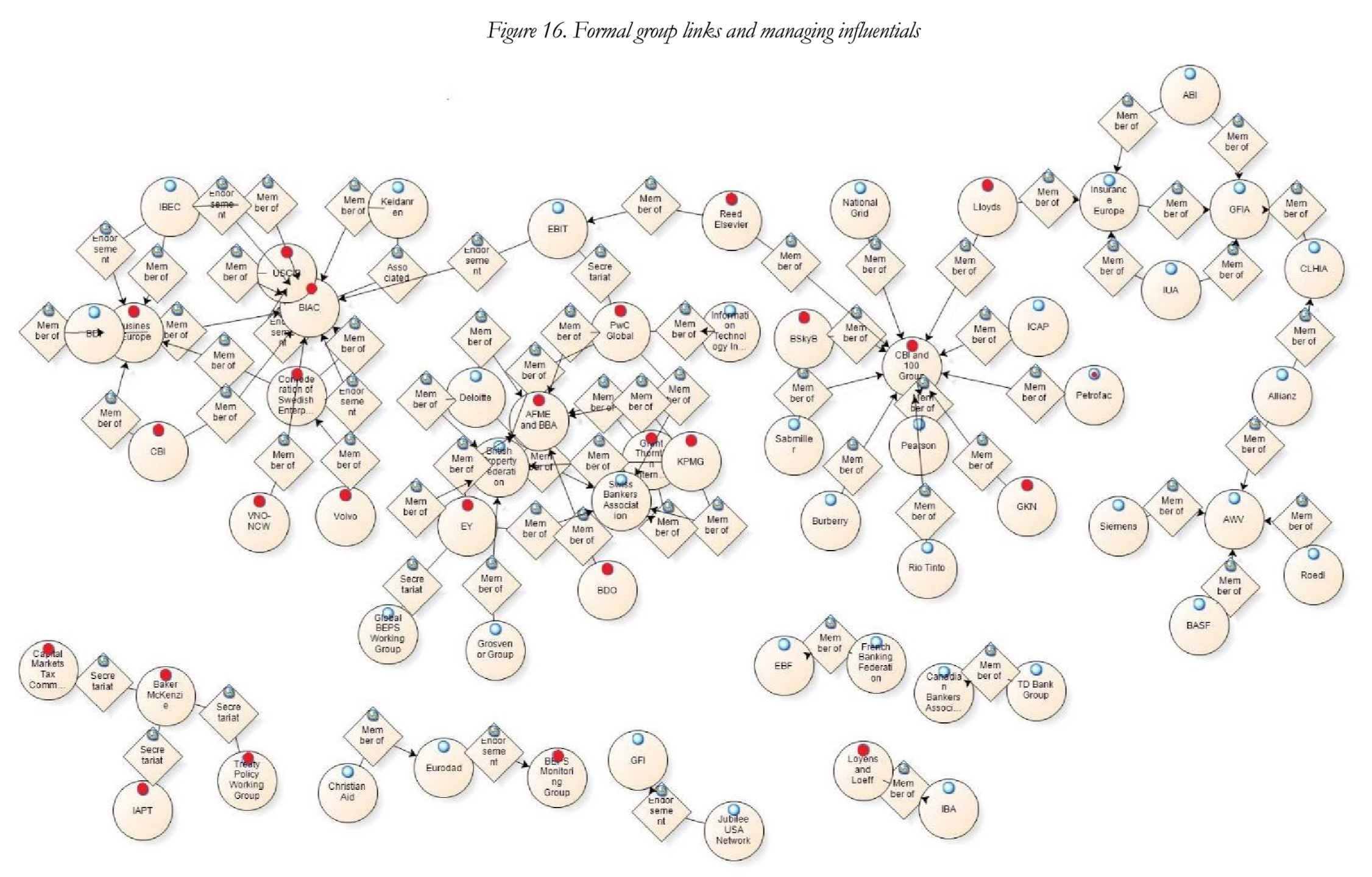

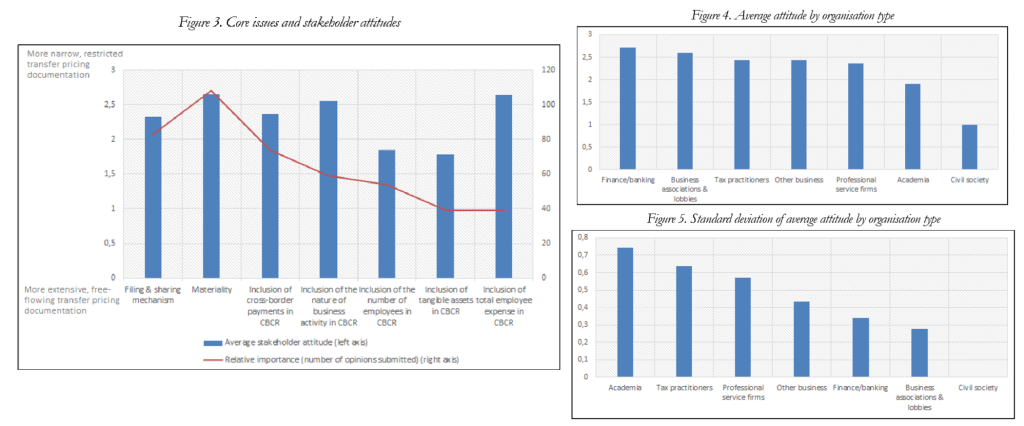

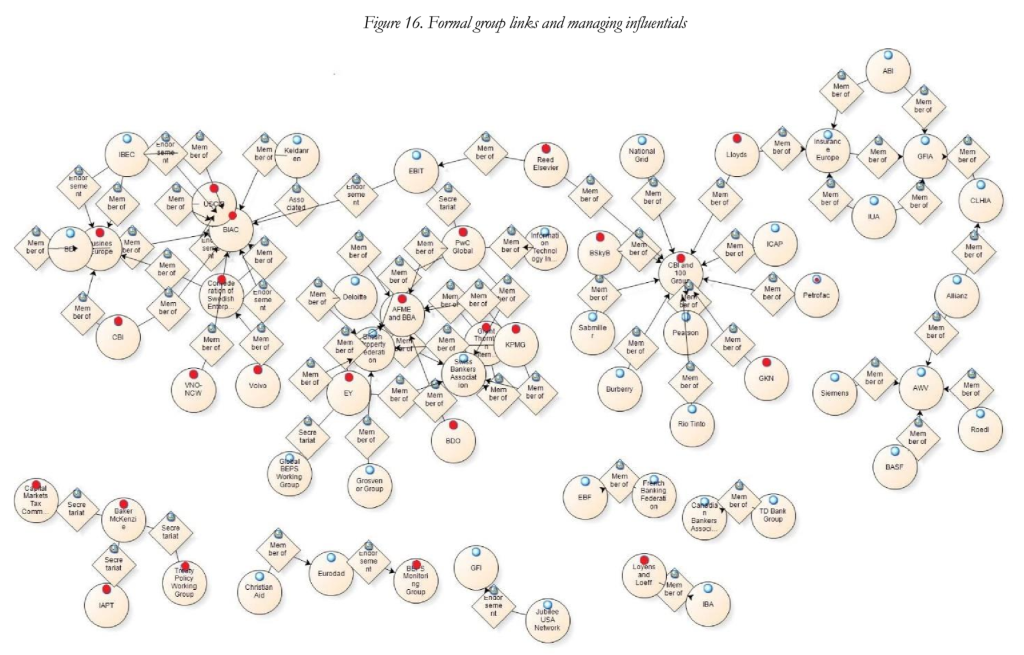

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process.

The analysis goes to a much more detailed level, tracing the paths of leading individuals in the process, identifying ‘professional competition’ as a key factor, where “influence in highly technical policy discussions is contingent upon expertise (being able to speak authoritatively) and networks (being listened to)… I distinguish two types of influential professional: career diverse professionals (“octopuses”) and well-connected specialists (“arrows”). The former are influential because of their varied expertise, the latter because they are respected through key tax/transfer pricing networks.” In figure 16 (click to expand, as ever), the red dots indicate organisations with a ‘managing professional’ who is influential in the process. The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions:

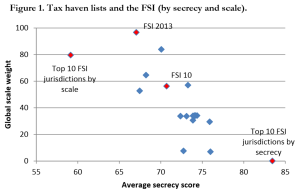

The full thesis contains a great deal more, including on the career paths of influentials. These are just some of the broad conclusions: Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).

Figure 1 compares some FSI findings with the most commonly used lists (the blue diamonds). Two points can be seen clearly: first, most lists capture less than half of the global market (only one captures more of the market than the ten biggest jurisdictions); and second, most lists are a little more secretive than the FSI in general, or the top ten FSI jurisdictions (albeit not nearly as secretive as the ten most FSI secretive jurisdictions, which together account for c.0% of the global market).