Here’s a quickish breakdown of Google UK’s accounting for the HMRC audit which has just been settled. It raises a serious question over how much – if even any – of the £130m actually relates to a challenge against international profit-shifting. And brings us that bit closer to crossing the Rubicon of corporate tax transparency…

Credit where credit’s due: this is entirely down to the digging of Bloomberg’s Jesse Drucker (unless I’ve made any mistakes, which will be my fault alone). It is however almost entirely Jesse’s fault that we’re still seeing headlines about Google (even if they don’t all credit him).

The UK subsidiary’s accounts to 2015 – which include the announced deal with HMRC – became public yesterday, and Jesse’s scoop is based on putting together the notes to the financials over the last few years, to identify a significant inconsistency in the story.

#Googletax: A triumph against profit-shifting?

The spin from Google, and also the UK government, most notably Chancellor George Osborne but also HMRC, has been that the £130m over ten years represents the fruits of a crackdown on international profit-shifting. After all, this is where public anger and policy pressure has been directed. And as a consequence, all the reporting has followed suit.

Google’s Matt Brittin even claimed specifically that the settlement reflected the new tax rules (by implication, the OECD BEPS changes and the government’s introduction of the Diverted Profits Tax) – which, while patently nonsense (neither change is backdated, let alone to 2005), confirmed the impression that this was about profit-shifting.

The first cracks were suggested by the Times’ remarkable story, in which Alexi Mostrous uncovered that HMRC “officials are understood to have concluded that the company’s offshore arrangements were legitimate”, and not subject to the Diverted Profits Tax (or ‘Google Tax’, a name briefed by officials upon its introduction).

The story in the accounts

The short version: some, and quite possibly all, of the settlement does not relate to international profit-shifting.

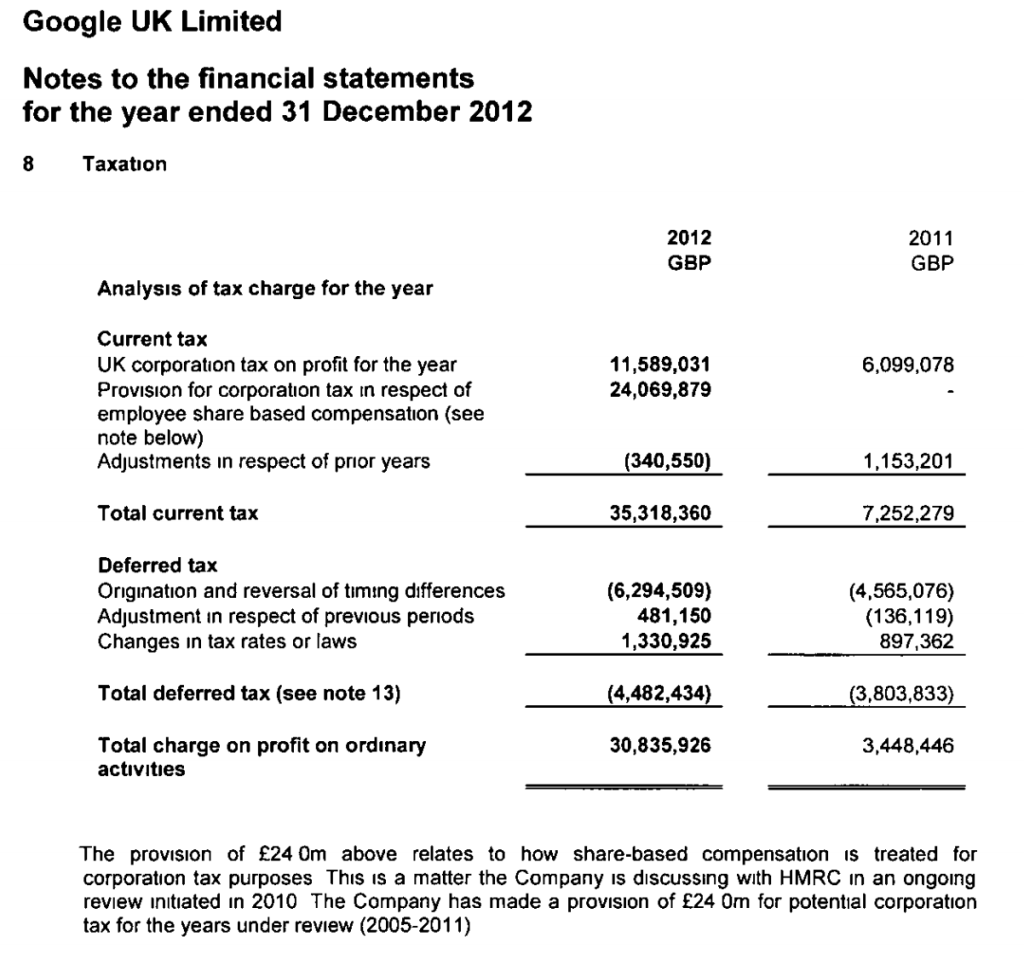

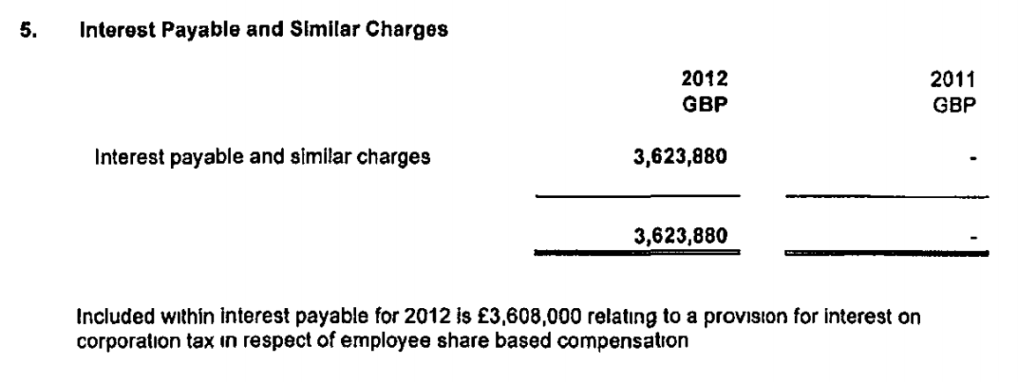

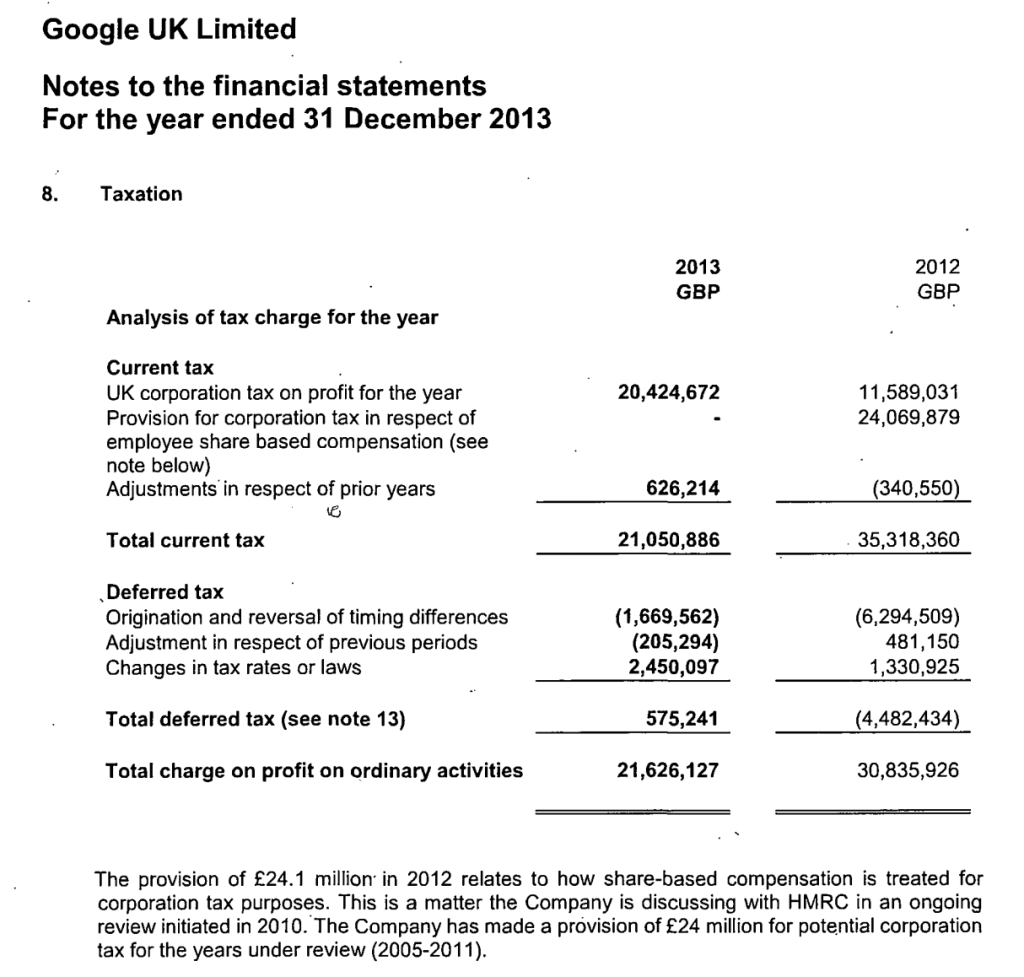

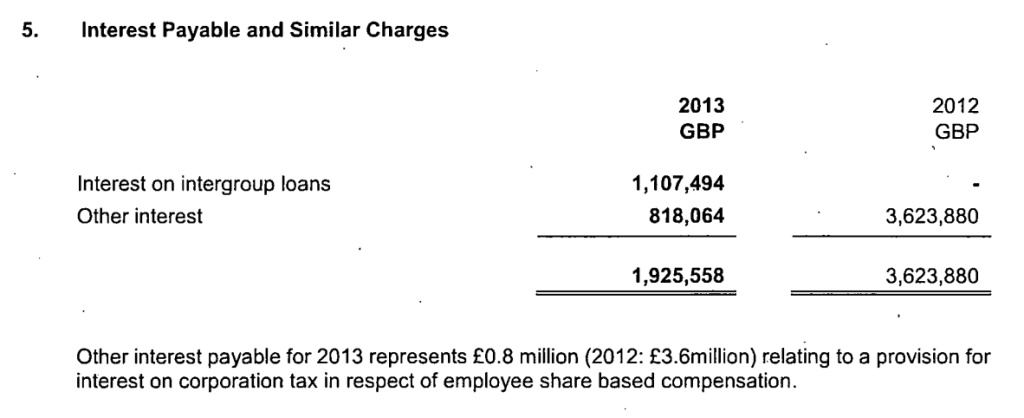

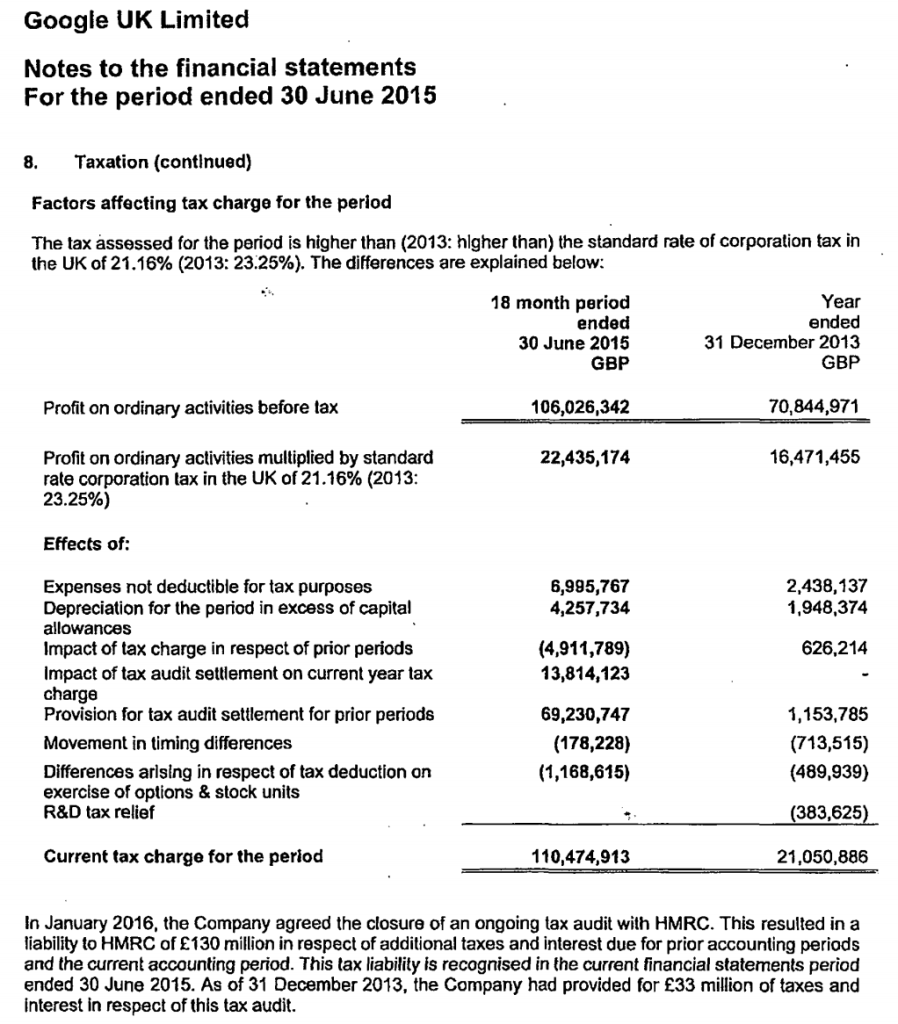

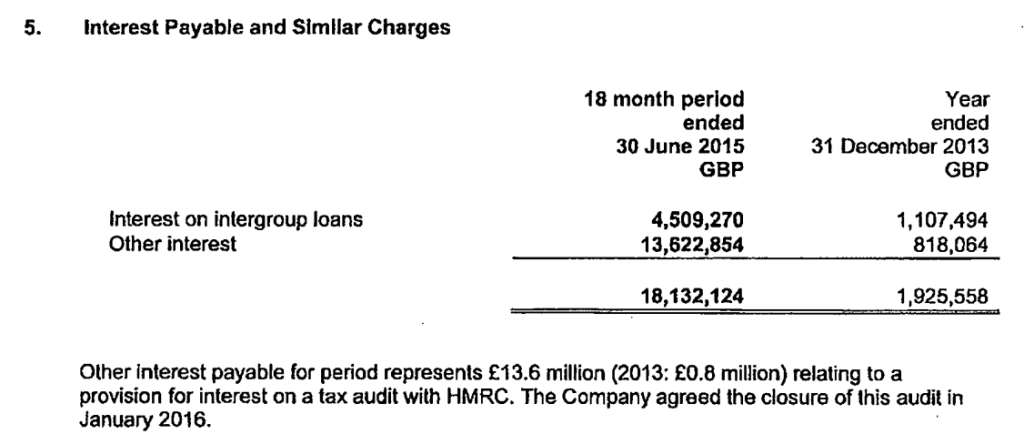

Here goes. Over the years since 2010 when the HMRC ‘open audit’ (#opennotopen) started, Google made provisions for the tax and interest that they thought they would eventually have to pay. These provisions feature, respectively, in notes 8 (tax) and 5 (interest) of the financial accounts.

First, the accounts to 2012 contain a provision of £24m for tax, and £3.6m for interest. The key point is the language. Google is specific that the provisions relate, indeed, to the HMRC audit – but only for ‘corporation tax in respect of employee share based compensation’. This is presumably a stock option scheme of some sort – nothing whatsoever to do with the widely discussed international structures that Google uses.

The accounts to 2013 show a small increase in the provisions, with the same details.

Finally, the newly released accounts (covering a year and half, after a change of accounting date) show a substantial increase in the provisions, and notes that £33m was the previous provision that now forms part of the overall £130m liability.

Finally, the newly released accounts (covering a year and half, after a change of accounting date) show a substantial increase in the provisions, and notes that £33m was the previous provision that now forms part of the overall £130m liability.

Where does that leave us? Google’s accounts show that the earlier provisions, which by 2015 are valued at £33m, are:

- The only provisions made in relation to the HMRC audit of tax years from 2005 onwards (with the exception of £1m+, see below); and

- Related only to employee share based compensation schemes.

What does it mean?

One possibility is that the £33m, a quarter of the announced settlement, had nothing to do with international profit-shifting – but that the remaining three quarters did. This would imply that Google was sufficiently confident throughout that although it was being audited on everything, it only provisioned in respect of this one element; and was then surprised.

Another apparent possibility is that (more or less) the entire £130m relates to this share scheme, in which case the settlement barely relates to the international profit-shifting issues over which credit has been claimed.

Most remaining possibilities, assuming no errors of accounting or my assessment above, would appear to lie in between these two polar suggestions: on which basis something between roughly a quarter and the entirety of the settlement does not relate to profit-shifting. Jolyon Maugham has neatly pulled out the additional, £1m+ provision for corporation tax that I’ve glossed over above and makes the case that there were indeed two distinct disputes, each eventually settled for liabilities in the tens of millions of pounds.

No, what does it actually mean?

Thought you’d never ask. The main effect of this curious story, and the ongoing reporting, will be to raise even more questions about this deal – and in particular, for the government and the Chancellor about how it was presented to the public. Google have batted back the questions from Bloomberg, but the Public Accounts Committee may have more leverage.

Any further unravelling will of course lead to even greater pressure in two areas: first, for greater transparency in this particular case (which will increasingly appear to violate taxpayer confidentiality – as the pronouncements of the Chancellor and HMRC may be felt to have already done); and second, for a powerful policy response that will provide the public with the kind of reassurance that is currently, painfully absent.

As I wrote previously, this would take the form of committing to publish the OECD standard country-by-country reporting (CBCR). It could come unilaterally from Google (perhaps unlikely, but don’t rule it out); or it could from the government. And in fact, since I wrote about this, and called for the same on the Today programme, the Chancellor has indeed pledged his support for public CBCR. {One to file under ‘correlation is not causation’, but at the deeper level not – public CBCR is the original Tax Justice Network policy proposal, and has gone from being written off as lunacy in 2003, to being on the verge of reality. File instead under ‘Advocacy successes where attribution is actually not unreasonable’.}

What remains is for this pledge to be made specific: for the UK to announce and deliver legislation mandating publication of country-by-country reporting, and to work publicly and privately to ensure that European Commission – currently sitting on the impact assessment they commissioned from LuxLeakstransparency champions PwC – makes the same call. An unparalleled step change in the accountability of multinationals, tax authorities and – in the tax sphere – governments too, is now within reach.